In March 2013, Americans were gripped by television coverage of a trial involving two high school football players from Steubenville, Ohio. They were charged with the rape of an intoxicated 16-year-old girl and with posting images of the assault on social media. The prosecution claimed the sex was not consensual because the victim was too intoxicated to consent. A defense attorney offered a different account: the victim voluntarily drank alcohol, went willingly with the boys, and “didn’t affirmatively say no.” He continued, “The person who is the accuser here is silent just as she was that night, and that’s because there was consent.”

Nothing is out of the ordinary in this line of legal argumentation. Lawyers presented arguments to help their clients which meant getting to the heart of matter: whether the sex was consensual. But the varying explanations offered by opposing attorneys shed light on broader questions of consent: What is meaningful consent? Does silence imply consent? What role does power play in assessing whether a person freely gave consent or was coerced?

These questions, among others, are inherently sociological. For one thing, people construct and enact consent in everyday life. Understanding how consent operates requires considering the unique circumstances where it manifests. The context might include the participants and their personal backgrounds, the stakes in the agreement (sex, property, etc.), and the culture surrounding the consensual activity and its various formal and unwritten rules.Equally important, consent is shaped by systems of power. Power is not inherently good or bad, but it is inescapable in all relationships, whether based on knowledge and expertise, economic, or social power (e.g., gender or race). The Steubenville rape trial is an example of the often-criticized confluence of jock and rape culture that empowers athletes to believe they have impunity. An unequal balance of power changes the character of consent insofar as it either eviscerates the possibility of consent or, at the very least, makes it difficult to ascertain whether consent is freely given. An examination of consent is an examination of power relations in society.

Ed: In the widely viewed Vine video below, members of the Oregon Ducks football team taunt opponents with a “No Means No” chant mimicking the Seminoles’ booster cheer. Oregon’s players were punished for trivializing rape and consent by using assault accusations against Seminoles player Jameis Winston as a joke.

Consent As a Social Phenomenon

Consent is a taken-for-granted social practice constructed through interaction. When we encounter a screen prompt on the Internet, we read and “consent” to lengthy terms presented in small font. In a hospital, a doctor recites an informed consent script to a patient that discloses the risks, benefits, and alternatives of a procedure before that procedure takes place. A romantic partner might use facial expressions to signal willingness to engage in sexual relations. These examples show that social relations create the terms of a consensual arrangement, and, in so doing, transforms impermissible to permissible conduct. In these cases, consent marks the difference between sharing personal information from invasion of privacy; surgery from medical battery; and sex from rape.

Defining consent is difficult because our “general consensus” definition of consent is nothing more than intuition. Discussions of consent’s meaning only arise when a person or a society feels there has been a considerable breach of consent. It is easier to discern what consent is not than to determine what consent is.Further, multiple individuals and institutions are responsible for assigning the meaning of consent, which can result in sharply different definitions. Research on sexual consent shows that legal definitions can obscure the importance of power relations based on age and gender. For example, children cannot legally consent to sexual activity with adults. Yet Heather Hlavka’s recent studies of child sexual abuse show that children can still assert their agency by deciding whether to report or tell someone about this breach in consent. Similarly, in my work on sexual sadomasochism (BDSM), I find that individuals in this subculture have explicit and elaborate discussions to negotiate and procure consent, even though some of the practices they are consenting to may subject a participant to what is otherwise criminal assault and battery. Consent thus implies social processes that are to varying degrees formal and informal, explicit and implicit, shared and coercive.

Consent also plays a central role in contract law because it signals intent and acceptance to terms and conditions of a deal. Though extensive contract law outlines meaningful consent in these circumstances, research shows consent plays a more subtle role in commercial settings. Rather than signing a detailed contract document, research from Stewart Macaulay and Lisa Bernstein shows that business people often value the other’s “word” and a handshake to represent consent. Aside from the obvious fact that resolving disputes outside formal legal channels is more cost-effective, these studies go on to speculate that some communities reject legal rules because they view law-based processes as destructively adversarial and negative for long-term commercial and interpersonal dealings (think, for instance, of those who avoid a prenuptial agreement, even when it would be prudent, because it means raising the specter of divorce and an implication of greed).

Indeed, the study of consent consistently shows a tension between how an individual defines consent versus how formalized laws and regulations mandate a particular manner in which it should be performed. In these cases, the established rules of consent often benefit and protect institutions rather than individuals. Socio-legal accounts of university Institutional Review Boards shows that increased expansion of rules and structures involving informed consent of human subjects in science research is not meant to maximize consent but to protect universities from legal risk. Similarly, studies in medicine, research by Renee Anspach and Robert Zussman reveal, show that doctors view informed consent as a legal requirement rather than as a mechanism to maximize a patient communication. With the help of hospital risk managers and medical malpractice insurance carriers, doctors deliver the legally minimal amount of information to patients.

Resistance To Affirmative Consent

If consent’s meaning varies, it seems that explicit, affirmative consent could resolve a lot of arguments before they start. However, logical efforts to make consent more explicit have faced considerable backlash and skepticism.

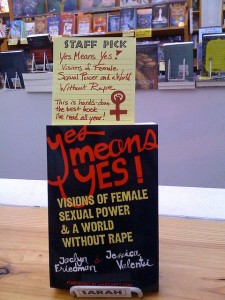

The primary criticism to affirmative consent—what many call a shift to the “Yes Means Yes” perspective and away from the “No Means No” ideal—is that this approach is unnatural and cumbersome. A recent example comes from the California legislature, which passed a law in September 2014 that requires colleges and universities to apply an “affirmative consent” standard for disciplinary proceedings involving sexual assault. The law clarifies that silence is not equal to consent, though critics point to ambiguity in how explicitly and frequently consent should be obtained. Some seem to believe obtaining all that consent really kills the “mood.” As Hans Bader at the San Francisco Chronicle wrote in an editorial, “this demand seems to be based on the false idea that the more explicit consent to an activity is, the more pleasurable the activity will be. But in the real world, the opposite is usually true, and the explicitness of consent is a bad measure of an activity’s welcomeness or enjoyability.”More important, the affirmative consent laws do not consider cultural constructions and power differentials between intimate partners. These affect whether and when someone comes forward to identify a breach in consent, the likelihood that such a breach would be normalized or overlooked by authorities, and how stories of consent and non-consent are told and understood by media and the public. Put another way, some critics suggest that these policies rest on assumptions that sexual assault is really just a misunderstanding rather than an act of power, control, and violence.

Resistance to affirmative consent reflects the cultural notion that explicit consent is artificial and unsatisfying. But there are plenty of cultures and subcultures in which explicit consent is taken seriously and doesn’t dampen the experience. Individuals in the BDSM subculture I have studied rely on consent to differentiate between acts of pleasure from acts of harm and violence. The community adheres to a fairly institutionalized framework that mandates a certain level of communication and disclosure before engaging in activities they refer to as “scenes.” Those unwilling to learn and play by the cultural rules are viewed as unlawful community members or even outsiders.

Changing the Culture of Consent

Should all forms of consent be affirmative, actively constructive by all actors involved? No.

There are circumstances in which affirmative consent is difficult due to asymmetries of power, knowledge, and expertise. Imagine yourself in a doctor’s office, presented with options that might predict, diagnose, or treat a medical condition. Most likely, you would ask for the doctor’s opinion about which option is best for you, since you are unlikely to be an expert in the condition or know enough medical terminology to determine your best course of treatment. Isn’t that, after all, why you’ve gone to a doctor? Indeed, this is consistent with a study by Christine Lavelle-Jones and colleagues in which medical patients had little recollection of their informed consent discussion—in fact, 69% admitted that they hadn’t read the consent forms they signed.

So, too, can we return to minors. The laws in place regarding the consent of a minor are not only premised on the idea that the minor may not have enough experience or knowledge to understand the agreement, but also on the idea that the other, older party is likely to have more power than the younger. That is, there may be an agreement, but the law considers it exploitative because of the asymmetry.As an oft-neglected area of social life, consent can be treated flippantly, and that can lead to an abuse of power. Taking consent seriously—that is, knowing the context and stakes of an agreement—keeps us all mindful that consent (like other social phenomena) is complicated by power imbalances. Aspirations toward broad policies based in affirmative consent are commendable, but remain a work in progress. At least, much like opening up the opportunity to discuss what individuals want—and do not want—whether in bed or at a used car lot, talking about consent is a good start.

You can’t get to “yes” without first asking a question.

Recommended Reading

American Civil Liberties Union of Illinois. 2014. “Racial Disparity in Consent Searches and Dog Sniff Searches: An Analysis of Illinois Traffic Stop Data from 2013.” This report shows considerable racial disparities in policing and questions whether Hispanic and black drivers consent to traffic stops voluntarily or through tacit coercion.

Jill Fisher. 2009. Medical Research for Hire: The Political Economy of Pharmaceutical Clinical Trials. New Brunswick, NJ and London: Rutgers University Press. Through ethnographic accounts, this book reveals how research coordinators deviate from informed consent procedures to develop trust and rapport with patient-subjects.

Stewart Macaulay. 1969. “Non-Contractual Relations in Business: A Preliminary Study,” American Sociological Review 28(55):145-164. A classic study that highlights how some prefer a handshake to a contract, because the cost of devising and enforcing a contract outweighs the benefit of making a deal and maintaining a trusting relationship.

Anastasia Powell. 2010. Sex, Power, and Consent: Youth Culture and the Unwritten Rules. New York: Cambridge University Press. This book provides a framework for understanding the development of rules for sexual negotiations and consent within youth culture and the gendered power relations that emerge.

Jill Weinberg. 2014. “Regulating Consent: Policing Good and Bad Pain Using Law, Rules, and Norms” Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Sociology, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL. This project compares the BDSM and mixed-martial arts subcultures’ responses to law through the creation of norms of consent that regulate behavior in activities where pain is central.

Comments 6

Elaine — January 5, 2015

This morning 13 Dalhousie University (Halifax, Nova Scotia) male dentistry students were suspended for an interim time for a Facebook page they created which spoke of wanting to "hate" rape female classmates and chloroform them. The University was pressured into taking some form of action. However, before we condemn these male students, we need to remember that each year hateful things are said and done by male students against not only female students but women in general, publicly, with little consequence.

I believe it would help immensely if we can understand what is going on sociologically in terms of why male students feel it is acceptable to even suggest that rape is okay, walk in parades shouting rape and sexual assault slurs against women, why female students are afraid to come forward--and, why those in power in academia do not want to deal with these issues and students.

Currently, we have discourses ranging from burn these male dental students at the stake to they are contrite and must not be expelled and have their careers destroyed.

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/dalhousie-suspends-13-dentistry-students-from-clinic-amid-facebook-scandal-1.2889635

I have just finished an undergraduate degree and it seems nothing is changing. It deeply disturbs me that we will continue to read headlines about these types of destructive attitudes and behaviours against women and which greatly impact higher education female students.

The Social Construction of Consent - Treat Them Better — January 5, 2015

[…] The Social Construction of Consent […]

The Social Construction of Consent | Sociology 316: Self and Society — March 13, 2015

[…] An interesting article by The Society Pages about power structures and the social construction of consent: http://thesocietypages.org/papers/consent/ […]

Queer Eye for the…Affirmative Consent Debate? - Girl w/ Pen — August 5, 2015

[…] feel entitled to sexual activity without regard for their partner’s willingness. (Entitlement and willingness are, of course, deeply […]

Queer Eye for the…Affirmative Consent Debate? | — August 10, 2015

[…] feel entitled to sexual activity without regard for their partner’s willingness. (Entitlement and willingness are, of course, deeply […]

Book Review: Missoula: Rape and the Justice System in a College Town | on fear and love — November 12, 2015

[…] of those involved. No certainly means no, but the edges blur when you have to ask: when and how was consent given? When and how was it taken away? Is it rape if the victim cannot verbally say no because she […]