I’m thrilled to bring this interview with Joanne C. Bamberger, editor of the new anthology Love Her, Love Her Not: The Hillary Paradox (She Writes Press), to Girl w/Pen. Joanne and I were both part of the first class of the Women’s Media Center’s Progressive Women’s Voices program waaay back, and I’ve been following her writing with admiration ever since. An entrepreneurial journalist and award-winning writer, Joanne is the publisher and editor in chief of The Broad Side, a digital magazine of women’s commentary. Joanne was chosen for the Forty Over 40 “disruptor” list for her work in amplifying the voices of women for political and social change, and was awarded the 2013 Advocacy Innovator Award by Campaigns & Elections magazine. Working Mother Magazine has called her one of the most “powerful” moms in social media. Her new anthology explores the question of why so many Americans, especially women, have such complicated and conflicting feelings when it comes to one of the most well-known and admired women in the world — Hillary Rodham Clinton. She’ll be moderating a panel, with contributors Veronica Arreola and Emily Zanotti, TONIGHT at Women and Children First in Chicago at 7:30pm. If you’re local, I invite you to join me there!

I’m thrilled to bring this interview with Joanne C. Bamberger, editor of the new anthology Love Her, Love Her Not: The Hillary Paradox (She Writes Press), to Girl w/Pen. Joanne and I were both part of the first class of the Women’s Media Center’s Progressive Women’s Voices program waaay back, and I’ve been following her writing with admiration ever since. An entrepreneurial journalist and award-winning writer, Joanne is the publisher and editor in chief of The Broad Side, a digital magazine of women’s commentary. Joanne was chosen for the Forty Over 40 “disruptor” list for her work in amplifying the voices of women for political and social change, and was awarded the 2013 Advocacy Innovator Award by Campaigns & Elections magazine. Working Mother Magazine has called her one of the most “powerful” moms in social media. Her new anthology explores the question of why so many Americans, especially women, have such complicated and conflicting feelings when it comes to one of the most well-known and admired women in the world — Hillary Rodham Clinton. She’ll be moderating a panel, with contributors Veronica Arreola and Emily Zanotti, TONIGHT at Women and Children First in Chicago at 7:30pm. If you’re local, I invite you to join me there!

DS: Your book’s title, Love Her, Love Her Not, evokes that game in which one person seeks to determine whether the object of their affection returns that affection or not. Hillary Clinton certainly wants the affection of culturally and politically astute women like those who’ve contributed to this anthology. By embracing the range of our complicated feelings, what kinds of feelings—and thoughts—do you hope the book itself will spark?

JCB: My hope is that the essays in LHLHN will help voters, especially women voters, examine their underlying feelings about Clinton. So many people say, “Oh, I don’t like her. I could never vote for her.” But when those same people are asked why they don’t like her, they’re stumped for an actual reason. So when I gathered the writers for this project, and we talked about essay topics, I asked each writer to really dig deep about the “why” question. What I found was that since we can only view any candidate through the lens of our personal experiences, those experiences significantly inform our feelings about her, rather than forming our opinions about her based on Hillary’s experience and credentials.

In many ways, how we view Hillary Clinton is really more about ourselves than about her. I believe that until women voters can work through their own feelings about Hillary, as well as women leaders in general, and what we expect of women, we won’t be able to elect a woman to the White House.

DS: You’ve brought together writers who are diverse in age, walks of life, race, and political affiliations. What were the most surprising through-lines in these essays, if indeed such through-lines exist?

JCB: One of the most surprising things to me was that so many writers still judge her for not leaving her husband after the Monica Lewinsky scandal. Even for the writers who initially judged her for being open about her personal political ambitions – and viewed her decision to stay in her marriage as a political calculation rather than a marital one – and have changed their minds about that judgment 20 years later, it was just very surprising to me that people judge her negatively for her decision when she was the wronged party in that episode.

Another theme I found fascinating was that while each essay topic was different, each writer was willing to take a step back and really view their feelings about Hillary through a microscopic lens and be really honest in the positives and negatives about Clinton. I’d characterize that kind of “through-line” as finally being able to see Hillary Clinton as a 3-D person, rather than the 2-D portrayal of her we are fed by most of the media, and to re-examine our ideas about her on a truer 3-D level. And isn’t that how we all want to be viewed? Unfortunately, we live in a time were media boil us all down to 2-D versions of ourselves. We won’t be able to elect a first woman president until we can look at ourselves, as well as Hillary, as fully-formed, three dimensional women who, by definition, are full of contradictions.

DS: In your earlier book, Mothers of Intention, you document how women and social media are revolutionizing politics and the uphill battle women still face in the world of politics and activism. How does a grandmother running for president change politics? And what do you make of the way media (social and otherwise) represent and portray her candidacy this time around?

JCB: Since we have had so many grandfathers run for president where that fact hasn’t been a substantive issue at all (most infamously, Mitt Romney with his 23 grandchildren and counting), having a woman who happens to be a grandmother running should not be an issue, either. Sadly, we still live in a society where women are still judged – decades after “women’s liberation” – through a traditional, gendered lens.

Unfortunately, few reporters or pundits are doing anything to change our views of women like Clinton. It certainly doesn’t help with how we view women of a certain age when women of younger generations use outdated language to discuss people like Hillary. Recently, a TIME Magazine reporter who’s written a book about women political leaders, said that grandmothers are viewed as “biddies,” suggesting that such an idea harms their chances of leading.

It seems we can’t escape media sexism when it comes to Hillary Clinton. In 2008, some questioned whether a hormonal Hillary should get anywhere near the “nuclear button,” channeling stereotypical worries about hysterical women. Now, a post-menopausal Hillary gets portrayed by Donald Trump (who is older than Hillary) as not having stamina, and reporters question whether she’s too old to run for president, yet they don’t make it as much of an issue for Bernie Sanders, who is several years older.

Statistically, since women live longer than men, and Clinton, at 68, has a life expectancy of at least 85, maybe we should take a more serious look at the fact that her older male candidates statistically have shorter life spans. 🙂

Until we can take the gendered filter off the lenses through which we view candidates, sadly will be an issue. Just as with the studies that show that woman candidates have to be likable for women voters to view them as “qualified,” yet when don’t require that of male candidates. I just hope I live long enough to see us toss those outdated gendered ideas out the window. Sadly, I’m not holding my breath.

DS: In so many ways, as you suggest, the debate seems as much about us as her. I love the title of a piece Jessica Grose wrote in Elle, “Have We Gotten Less Sexist Since Hillary Clinton’s Last Run.” Have we? And about that “we”: it’s easier to claim sexism when haters are men. Are there ways in which women, in our own love/hate, are enacting sexism too? If yes, how so?

JCB: Some of that sexism comes from the grandmother question we talked bout earlier.

Women, sadly, aren’t exempt from sexism when it comes to Hillary. The idea that some women have that a former first lady has no place running for national elective office, regardless of her own personal qualifications, is blatantly sexist. That many women loved her as secretary of state but loathe the idea of her as president is sexist. Women’s sexism toward Clinton is sometimes less obvious than the sexist commentary thrown her way by men, but it’s there – our continued questioning of her fashion choices, whether she’s strong enough to be commander in chief, and, yes, whether she is “likable” enough to women – all sexist, even if those same women can admit that her resume more than qualifies her to run for president.

DS: If you were to design a Hillary Studies course for college students (as you hint at in the introductory essay to the book!), what would the curriculum be?

JCB: It would be easy to put together a curriculum, with academic articles and books being written every year about her, and I think the focus would be on gender, media and whether we are, in fact, a post-feminist society.

While I know that many women younger than myself believe that we have finally reached a point where we are post-feminist – meaning we don’t need a woman to advocate for feminist issues, and that men who identify as feminists can do just as good a job as a woman, I disagree. And I think that a Hillary Studies curriculum would focus on: (1) the media sexism Hillary endured during the 2008 campaign and how all women are negatively impacted by that, (2) how Hillary’s leadership potential is undermined in our world of memes, and how those undermine all women, (3) right-wing, gendered hate speech (one example – “rhymes with blunt”) against Hillary and the negative impact that has on other women who follow her onto the national stage, and (4) what has to happen in society to get beyond these issues to finally be able to envision a woman sitting in the Oval Office in her own right so that we can actually elect one.

DS: Anything else you’d like readers to know?

JCB: One of my favorite things about the essays in the book is that they are all so nuanced, and written with insight and yes, humor. I had thought that the essays would fall neatly into three categories – the lovers, the haters, and those still on the fence. But because all the writers – even the ones who aren’t Hillary Clinton fans – could recognize the importance and the value of having someone like Hillary on the national stage, I couldn’t package them that way. If more of the coverage of her as a candidate was as thoughtful as the essays in LHLHN, we would be having a very different national conversation about her. I hope the readers of LHLHN will enjoy the various perspectives from these amazing women.

Buy the book from Women and Children First, right over here.

Read more about Joanne: www.joannebambeger.com

***

Stay in touch! I invite you to join the Girl Meets Voice Facebook community, pin with me on Pinterest at Tots in Genderland, follow @girlmeetsvoice, and subscribe to my quarterly newsletter to keep posted on coaching, workshops, writings, and talks.

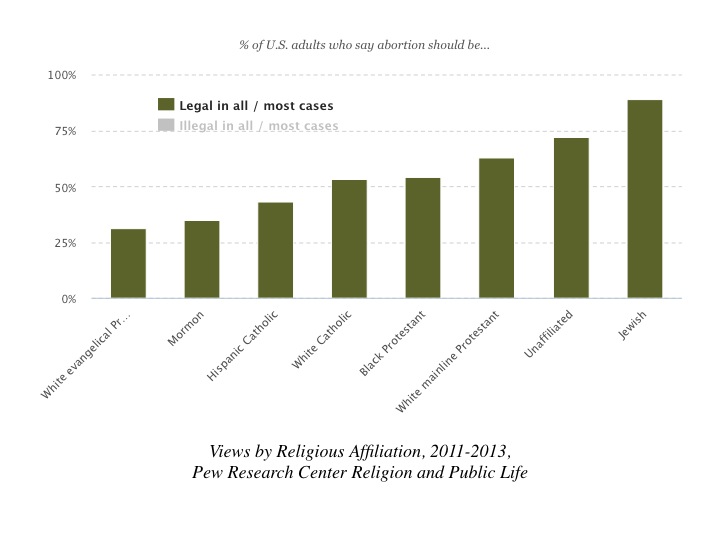

When it comes to anti-abortion activism, sociologist

When it comes to anti-abortion activism, sociologist