Upon first glance, men who identify as “bronies” (a subculture of men who like My Little Pony) seem to illustrate a fundamental transformation in masculinity. These men appear to be less stigmatized by association with something “feminine” or “feminizing” (like children’s toys initially marketed to young girls). New research by graduate students John Bailey and Brenna Harvey, however, found that even in a subculture formed around a seemingly emasculating hobby, participants still lob gendered and sexualized insults and epithets at one another. In his write-up on the research in The Guardian, Adam Gabbatt explained some of Bailey and Harvey’s findings in this way:

Upon first glance, men who identify as “bronies” (a subculture of men who like My Little Pony) seem to illustrate a fundamental transformation in masculinity. These men appear to be less stigmatized by association with something “feminine” or “feminizing” (like children’s toys initially marketed to young girls). New research by graduate students John Bailey and Brenna Harvey, however, found that even in a subculture formed around a seemingly emasculating hobby, participants still lob gendered and sexualized insults and epithets at one another. In his write-up on the research in The Guardian, Adam Gabbatt explained some of Bailey and Harvey’s findings in this way:

Bailey and Harvey found that even men who fancy My Little Pony cartoon characters are likely to scrap with each other using similar terms and putdowns to “normal” men, even to the point of using the same terminology, such as “faggot,” to police their environment.

One particular incident was a putdown from one member to another in an online brony forum that read: “Go be normal somewhere else, faggot.” While we might expect “fag” to be lobbed at members of the group by outsiders, it might seem odd that (at least some) bronies use the term as well.

Contemporary Western masculinity is in many ways characterized by these seeming contradictions. Consider what happened when the University of Oregon defeated Florida State University at the Rose Bowl earlier this year (to which CJ would like to add: “Yeah we did! GO DUCKS!”). In the post-game revelry, some of the Oregon players began to chant “No means no!” to the tune of the (racist) “War Chant” regularly sung by FSU fans. As ThinkProgress reported,

Contemporary Western masculinity is in many ways characterized by these seeming contradictions. Consider what happened when the University of Oregon defeated Florida State University at the Rose Bowl earlier this year (to which CJ would like to add: “Yeah we did! GO DUCKS!”). In the post-game revelry, some of the Oregon players began to chant “No means no!” to the tune of the (racist) “War Chant” regularly sung by FSU fans. As ThinkProgress reported,

The chant was almost certainly intended to target [Jameis] Winston [Florida State’s quarterback], who has been embroiled in a sexual assault scandal since 2012, when a female student accused him of raping her. He has not been officially charged or sanctioned for the incident, and won the Heisman Trophy amid the ongoing controversy.

Commentaries on this incident widely lauded it as a moment in which young men were collectively, publicly, shaming another man accused of sexual violence with a long time feminist slogan.

While on the surface these two events are incredibly different, elements connect the two. Among the bronies, a man chastised another as a “fag” in part to defend his own gender transgressive interest and identity and the community in which he participates. Among the Oregon Ducks, a group of men appear to be embracing the feminist principle that Sarah Silverman recently tweeted so eloquently (to the anger of at least a few men), “Don’t rape.” These examples involve men telling other men, “You are not masculine, and here is why… Oh, and I am (just in case that wasn’t clear).” The content of what makes someone masculine doesn’t actually matter nearly as much as the ability to deny that powerful social identity to others.

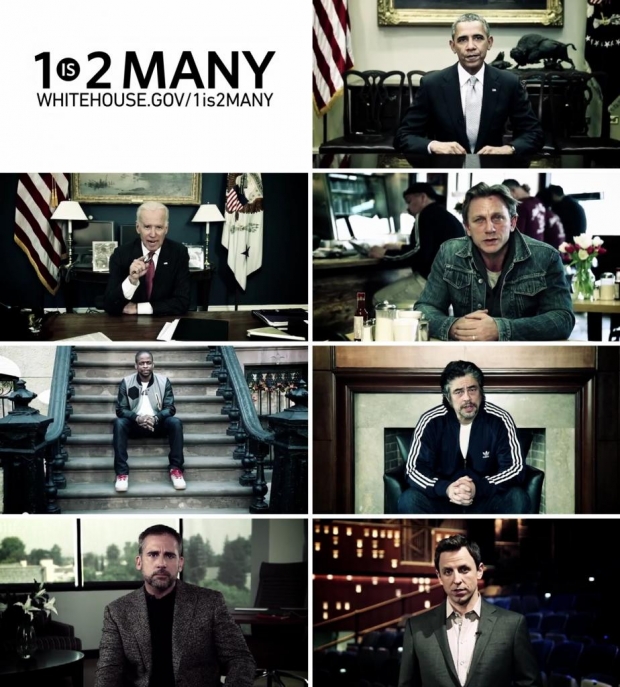

Now, don’t get us wrong; we are thrilled to see high profile athletes embracing the notion of consent and refuting sexual violence. Men publicly condemning sexual violence are important and can be extremely powerful. But, behind these statements is a protectionist ideology that involves men claiming to symbolically protect women from other “bad” and (importantly) “less” masculine men. The White House-sponsored “1 is 2 Many” public service announcement combats sexual violence using a similar tactic.  In the PSA, a group of professional actors, along with Vice President Joe Biden and President Barack Obama, call for an end to sexual violence and assault. Many say things like actor Daniel Craig, who says, “If I saw it happening, I’d never blame her. I’d help her.” Craig is probably most identifiable as having recently portrayed James Bond—a character who, among other things, is best known for having his way with any woman he chooses. But positioning sexual assault as something that other, bad, less masculine men do (like those, say, who lose football games) allows some men to say, “Real men don’t rape. And WE are real men.” But the “real men” discourse may be problematic in and of itself. (See the “My Strength is Not for Hurting” campaign for another example of this tactic).

In the PSA, a group of professional actors, along with Vice President Joe Biden and President Barack Obama, call for an end to sexual violence and assault. Many say things like actor Daniel Craig, who says, “If I saw it happening, I’d never blame her. I’d help her.” Craig is probably most identifiable as having recently portrayed James Bond—a character who, among other things, is best known for having his way with any woman he chooses. But positioning sexual assault as something that other, bad, less masculine men do (like those, say, who lose football games) allows some men to say, “Real men don’t rape. And WE are real men.” But the “real men” discourse may be problematic in and of itself. (See the “My Strength is Not for Hurting” campaign for another example of this tactic).

What all of these instances illustrate and what draws us to them is that they seem to illustrate (positive) changes in contemporary masculinity—young men engaging in activities stigmatized as feminine, athletes shaming one of their own for sexual assault, male politicians and actors publicly espousing an end to sexual violence. If, as activists have argued, a problematic aspect of masculinity is the fact that it entails putting others down, distance from femininity, and sexually dominating women, then we should be unequivocally celebrating these changes.

However, as we have written about before, gendered change is complicated. These changes illustrate that masculinities are flexible—sometimes incredibly so. Masculinities can be prodded and reworked in ways that incorporate practices and symbols not historically associated with masculinity at all. But, in reworking them, masculinity reveals that depriving others of this powerful social identity is often the key ingredient of the social identity. These transformations hold incredible potential. But, whether that potential is realized is an entirely different question. And that, it seems, is the next project: realizing potential for gendered change that does not revolve around repudiating less socially desirable gendered identities or rely on the methods of dominance involved in sustaining some forms of social inequality in the first place.

Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society invites submissions for a special issue titled

Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society invites submissions for a special issue titled

Their stories closely mirror those of the gay and lesbian teachers I interviewed for my recent book,

Their stories closely mirror those of the gay and lesbian teachers I interviewed for my recent book,