“Go Hermione!”

A young woman in my Sociological Theory class yelled those words as soon as she saw me pull up a clip of Emma Watson’s speech at the UN for the class to see. We were covering Charlotte Perkins Gilman that day, and I showed the video because I thought she articulated the core tenets of contemporary feminist theory pretty well. For ten minutes, my students sat in rapt attention as Watson explained how (1) gender inequality still exists, (2) gender binaries are socially constructed, and (3) masculinity isn’t healthy for men, either.

A young woman in my Sociological Theory class yelled those words as soon as she saw me pull up a clip of Emma Watson’s speech at the UN for the class to see. We were covering Charlotte Perkins Gilman that day, and I showed the video because I thought she articulated the core tenets of contemporary feminist theory pretty well. For ten minutes, my students sat in rapt attention as Watson explained how (1) gender inequality still exists, (2) gender binaries are socially constructed, and (3) masculinity isn’t healthy for men, either.

While these ideas aren’t new—Perkins Gilman voiced many of them over a century ago—Watson’s speech caught fire both in my classroom and on social media. What attracted the most attention was her call for men to join the HeForShe campaign as advocates for change. Within minutes, #HeForShe started trending on twitter. Within hours, male celebrities began posting pictures of themselves holding handwritten #HeForShe placards. This made me feel good about the world.

But it also made me sad.

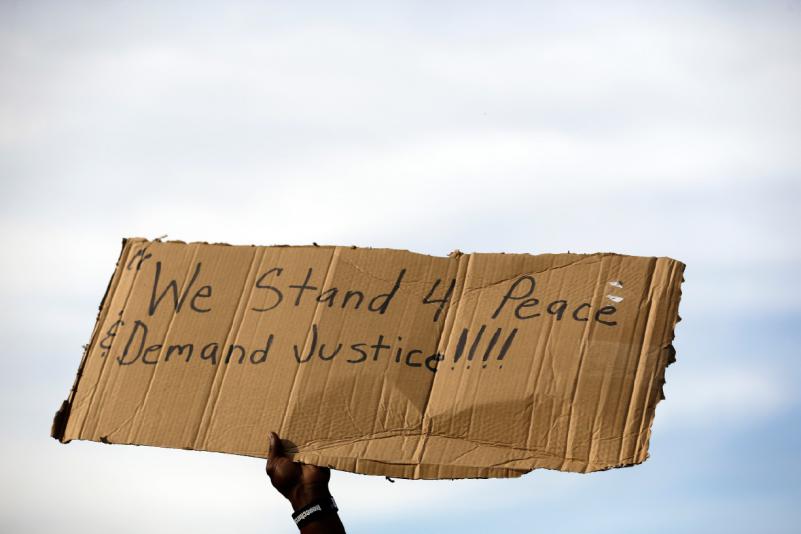

The reason for this is because the statistics Watson outlined in her speech have been articulated at conferences, panels, and rallies across the country for decades. In terms of pay, power, and prestige, women almost always lag behind men. Nearly a quarter of women in the US will experience severe physical violence from their intimate partners in their lifetime. However, people aren’t retweeting and sharing Watson’s speech solely because of the facts she cited. Instead, her speech went viral because of the audience who finally listened: men. And this is what made me sad.

We all know that the fight against domestic violence will never be won by women alone. Men need to be an equal part of the movement. Yet, the question of how to get them involved is still a subject of debate. One way to recruit them is to praise their presence and applaud them for voicing their solidarity. This is an effective strategy to get more men involved. It works.

However, there is a downside to this approach. Namely, celebrating the presence of allies can sometimes exacerbate the same inequalities that organizations like HeForShe are trying to combat in the first place.

I’ve seen this process firsthand. As a sociologist who spent roughly a year and a half doing ethnographic field work inside an agency that assists victims of domestic violence and sexual assault, one of the most common questions I get about my research is, “so, what is like to be a guy in a place like that?” Not many men work inside rape crisis centers or battered women’s shelters. Most of the time, when I was answering the crisis-hotline or helping clients fill out legal forms, I was the only man in the building. And while many people presume that this would make my research harder, it had the opposite effect. It made it easier.

I’ve seen this process firsthand. As a sociologist who spent roughly a year and a half doing ethnographic field work inside an agency that assists victims of domestic violence and sexual assault, one of the most common questions I get about my research is, “so, what is like to be a guy in a place like that?” Not many men work inside rape crisis centers or battered women’s shelters. Most of the time, when I was answering the crisis-hotline or helping clients fill out legal forms, I was the only man in the building. And while many people presume that this would make my research harder, it had the opposite effect. It made it easier.

You see, like Emma Watson said, domestic violence victim-advocates and counselors aren’t man-haters. This caricature is completely inaccurate. You know why? Because stereotypes like “feminazis” make it harder for them to help their clients.

The more judges and cops see staff at these agencies as spiteful and biased, they less likely they are to sign their clients’ Orders of Protection or dispatch officers to enforce them. Advocates and counselors don’t worry about what people call them—they have thick skin. What they care about is their clients’ safety. Debunking these “anti-male” myths is a way to help their clients.

So, how do they prove they don’t hate men? They applaud men who help out the least bit.

In many ways, this strategy makes sense. Staff at agencies like the one I studied are typically underpaid and overworked. Pats on the back are sometimes the only thing they can afford to offer in exchange for men’s help. In my book, I call these symbolic rewards “progressive merit badges,” and they were given to men who understood how domestic violence was really just a means for abusers to exercise power and control over their intimate partners.

While it might be easy to dismiss the progressive merit badges men can earn for helping out as inconsequential, that would be a mistake. In some careers, these stamps of approval have real value. I watched the men who earned them climb their career ladders quicker than their peers.

During my research, I watched male sheriff’s deputies promoted into better paying liaison positions because of their affiliation with the agency. I watched an assistant district attorney leverage his years of work with victims of domestic violence as a feature item in his successful campaign for judge. I watched a “batterer intervention facilitator” parley his experience counseling abusers into his own private practice.

In these cases, being an ally paid off—not just symbolically, but economically, too. This isn’t an isolated case. Privileging allies to combat social problems is, well… problematic.

To understand my concerns, first consider what it means to be an ally. An ally is someone who helps others solve their problems. Whites who fight racism, straight folks who battle homophobia, the wealthy who seek to end poverty; these actions are considered virtuous because of their presumed selflessness. We expect people of color, those who identify as queer, and the poor to fight to improve their condition. For whites, straight folks, and the wealthy, their privileged positions make their acts voluntary—they do it because they want to, not because they have to.

Second, under what conditions do allies become valuable commodities to social movements? Short answer: when others members of their privileged group behave badly. Without racism, there is no virtuosity in whites taking a stand against discrimination. Without homophobia, being a straight ally would be a meaningless term. For allies, their value is inversely proportional to the harm done by their social group.

To see this at work today, think about the recognition earned by men who declare their support for Emma Watson. The more credible we perceive the threats by some men to post nude pictures of her on the internet as revenge for her speech, the more valuable her male allies become. In other words, the more we fear gender terrorism by some men, the more we applaud other men for denouncing it.

The answer to this dilemma is not for women to do all the work themselves. Obviously, men’s presence is needed. Instead, the solution is to reflect on why male allies become such precious commodities in the fight against domestic violence.

Remember, not everyone has spare time, money, and energy to give; and not everyone can protest without fear for their personal safety. Conferring progressive merit badges to those who already have these privileges—especially considering their value in some career tracks—can unintentionally exacerbate the same state of gender inequality that is the root cause of domestic violence from the outset.

There is a lot of work to do, we need all hands on deck. Men’s help should be applauded just as any woman’s. But being a member of the group who created a mess should not be the criteria for celebration when a select few of them offer to clean it up.

______________________

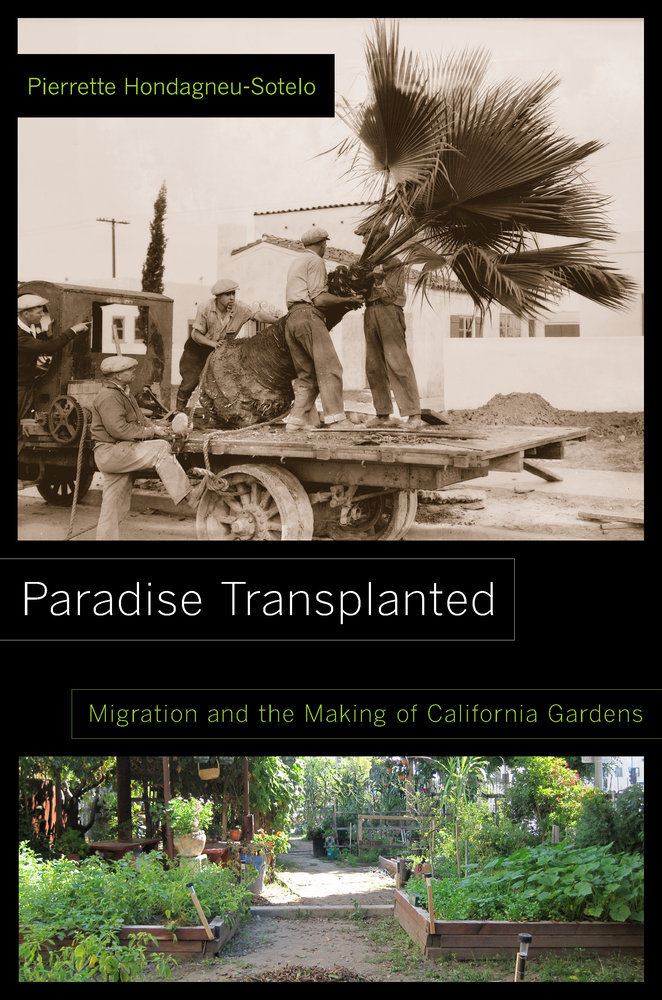

Kenneth Kolb is an associate professor of sociology at Furman University in Greenville, SC. He is the author of, Moral Wages: The Emotional Dilemmas of Victim-Advocacy and Counseling, University of California Press, 2014.

Kenneth Kolb is an associate professor of sociology at Furman University in Greenville, SC. He is the author of, Moral Wages: The Emotional Dilemmas of Victim-Advocacy and Counseling, University of California Press, 2014.

![]() Workplace consultant, coach and work-life advocate Rachael Ellison penned an excellent post chock full of qualitative data at HuffPo Parents last week, “Why Caregiver Discrimination Is Bad for Business.”

Workplace consultant, coach and work-life advocate Rachael Ellison penned an excellent post chock full of qualitative data at HuffPo Parents last week, “Why Caregiver Discrimination Is Bad for Business.”

A young woman in my Sociological Theory class yelled those words as soon as she saw me pull up a clip of

A young woman in my Sociological Theory class yelled those words as soon as she saw me pull up a clip of  I’ve seen this process firsthand. As a sociologist who spent roughly a year and a half doing ethnographic field work inside an agency that assists victims of domestic violence and sexual assault, one of the most common questions I get about

I’ve seen this process firsthand. As a sociologist who spent roughly a year and a half doing ethnographic field work inside an agency that assists victims of domestic violence and sexual assault, one of the most common questions I get about