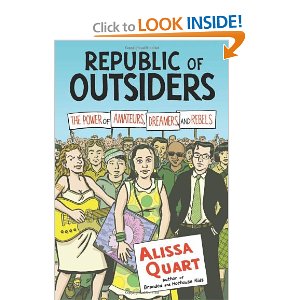

There are many reasons to check out veteran journalist Alissa Quart’s new book, Republic of Outsiders: The Power of Amateurs, Dreamers and Rebels. And not just because I love the graphic cover or because she is my good friend. Well, maybe those are reasons 2 and 3. But don’t take my word alone.

There are many reasons to check out veteran journalist Alissa Quart’s new book, Republic of Outsiders: The Power of Amateurs, Dreamers and Rebels. And not just because I love the graphic cover or because she is my good friend. Well, maybe those are reasons 2 and 3. But don’t take my word alone.

The book is generating some well-deserved buzz: Approval Matrix of New York Magazine, Flavorwire’s top books of August, excerpts in The Nation and O.

So what’s it about? Outsiders who seek to redefine a wide variety of fields, from film and mental health to diplomacy and music, from how we see gender to what we eat. Professional and amateur filmmakers crowd-sourcing their work, transgender and autistic activists, Occupy Wall Street’s “alternative bankers.” These people create and package new identities. They are “identity innovators”, pushing the boundaries of who they can be and what they can do–and moving the mainstream as they go.

My favorite chapter, no surprise, is the one titled “Beyond Feminism.” Here, Quart profiles a number of transpeople and reflects on how the thinking about gender-as-spectrum is moving the dial:

They were innovating their own identities but also trying to alter feminism itself. Transcending and remixing sex stereotypes, they believed, was a necessary next stage for the development of both men and women. In order to obtain greater equality for all, they thought, we must look again at how gender biases and clichés limit all of us.

Deeply reported, the book at large explores how, as stated on Amazon, “without a middleman, freed of established media, and highly mobile, unusual ideas and cultures are able to spread more quickly and find audiences and allies.” It’s a close look at those for whom being rebellious, marginal, or amateur is a source of strength.

Writes Publishers Weekly, in a starred review, “Quart’s profiles are thoroughly researched and admirably evenhanded.” Says Booklist, “Lots of good food for thought and solid inspiration for those who feel stifled by traditional choices.”

Ever feel like an outsider? Ever hunger for a sharp cultural analysis of how the margins inform the center? Folks, this book is for you.