New controversy about free condoms inspires this month’s column, a critique about student health and public health by Chloe E. Bird, Ph.D., senior sociologist at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation and co-author of Gender and Health: The Effects of Constrained Choices and Social Policies (Cambridge University Press).

The Affordable Care Act requires that birth control be made available through health plans, in some cases without co-pays or deductibles. That’s prompted religious institutions to object to paying for care that’s not consistent with their values. But Boston College’s recent steps to stop free condom distribution doesn’t involve sponsoring birth control—it involves location. Boston College Students for Sexual Health, an unofficial campus group formed in 2009, gives away condoms on a sidewalk next to campus and from about 15 dorm rooms, which the group calls “safe sites.”

The Affordable Care Act requires that birth control be made available through health plans, in some cases without co-pays or deductibles. That’s prompted religious institutions to object to paying for care that’s not consistent with their values. But Boston College’s recent steps to stop free condom distribution doesn’t involve sponsoring birth control—it involves location. Boston College Students for Sexual Health, an unofficial campus group formed in 2009, gives away condoms on a sidewalk next to campus and from about 15 dorm rooms, which the group calls “safe sites.”

Until recently, Boston College, a private Jesuit institution, appeared to have taken an approach common among Catholic colleges: tolerating condom distribution by its students as long as it was done offsite, but officially banning the activity on its property. There is some dispute about whether the college previously asked the student groups to stop the on-campus distribution program; however, it recently informed students that any reports that they were distributing condoms on campus would be referred to the student conduct office for disciplinary action. At issue is whether public health policy should protect such actions by students, or whether Boston College and other private universities can ban condom distribution on their property on religious grounds.

If this issue were to be decided on the basis of public health benefits, the outcome would be clear: Condoms indisputably prevent both unintended pregnancies and the spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Although abstinence is the only way to completely prevent pregnancy and STIs, it works only when practiced without exception. Students who have chosen sexual activity over abstinence could benefit from accessible distribution sites—and the numbers indicate that most do choose sex over abstinence. On the spring 2012 American College Association National College Health Assessment, 69.6 percent of college students reported having one or more sexual partners in the previous 12 months, and 27 percent reported having two or more.

Decades of research demonstrate that condoms do not cause individuals to have sex but do reduce rates of STIs, unwanted pregnancies and abortions. Moreover, a lack of available birth control has not been shown to be effective in either causing abstinence or preventing pregnancy and STIs. While a lack of access to condoms might lead students to employ other approaches to reduce the risk of pregnancy, condoms remain the best available option to prevent STIs outside of abstinence. Free distribution is particularly effective because cost has been shown to be a barrier to condom use, particularly among younger males. Consequently, publicly supported condom distribution programs have been both cost-effective and cost-saving.

A recent Guttmacher Institute report noted that unplanned pregnancies interfere with the ability of young women to graduate from college. They also increase the odds that a relationship will fail. And,

People are relatively less likely to be prepared for parenthood and develop positive parent-child relationships if they become parents as teenagers or have an unplanned birth.

Condom distribution programs have been shown to be highly effective not only in increasing condom use among sexually active populations, but also in promoting delayed sexual initiation and abstinence among youth. So both students and their future sexual partners stand to benefit from the free distribution of condoms. Clearly, condoms are critical to student health—especially women’s health.

To be sure, Boston College’s administration does not approach the issue wholly on the basis of public health considerations. The Catholic Church sets narrow limits on the use of condoms—to protect human life and reduce the transmission of HIV. But given the clear public health benefits of condoms, it does make sense to seek a path that honors the right of religious institutions to set limits consistent with their moral principles while also providing access to free condoms for those students who choose to use them.

Massachusetts public health officials, legislators and the general public will have to weigh the merits of allowing religious institutions to ban the free distribution of condoms. If they decide to respect and allow such bans, then perhaps they should consider joining Washington, D.C., and New York State in establishing condom distribution programs for all residents.

– Crossposted with permission from the Ms. Blog –

You heard about the letter: Princeton alumna Susan Patton

You heard about the letter: Princeton alumna Susan Patton  The folding of

The folding of  Earlier this month I wrote about

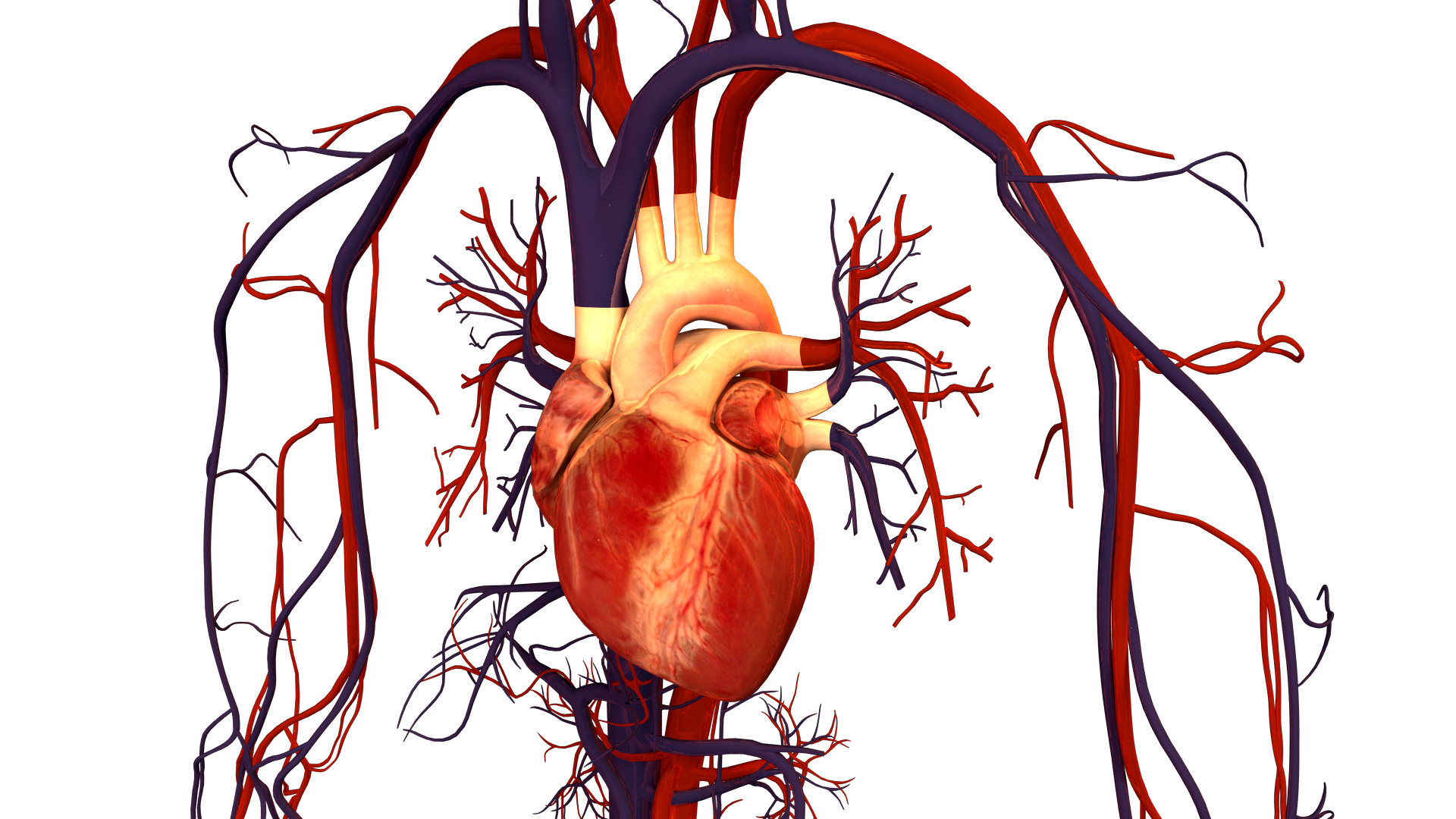

Earlier this month I wrote about  As a women’s health researcher, I am concerned about how long it is taking to bring attention and resources to this problem. After all, it has been decades since we’ve learned that cardiovascular disease affects women every bit as much–or even more–than it does men. Indeed, since 1984, cardiovascular disease has killed

As a women’s health researcher, I am concerned about how long it is taking to bring attention and resources to this problem. After all, it has been decades since we’ve learned that cardiovascular disease affects women every bit as much–or even more–than it does men. Indeed, since 1984, cardiovascular disease has killed  In celebration of International Women’s Day, UN Women has released an English-language song, “

In celebration of International Women’s Day, UN Women has released an English-language song, “ Yesterday in the New York Times, Tamar Lewin reported on

Yesterday in the New York Times, Tamar Lewin reported on