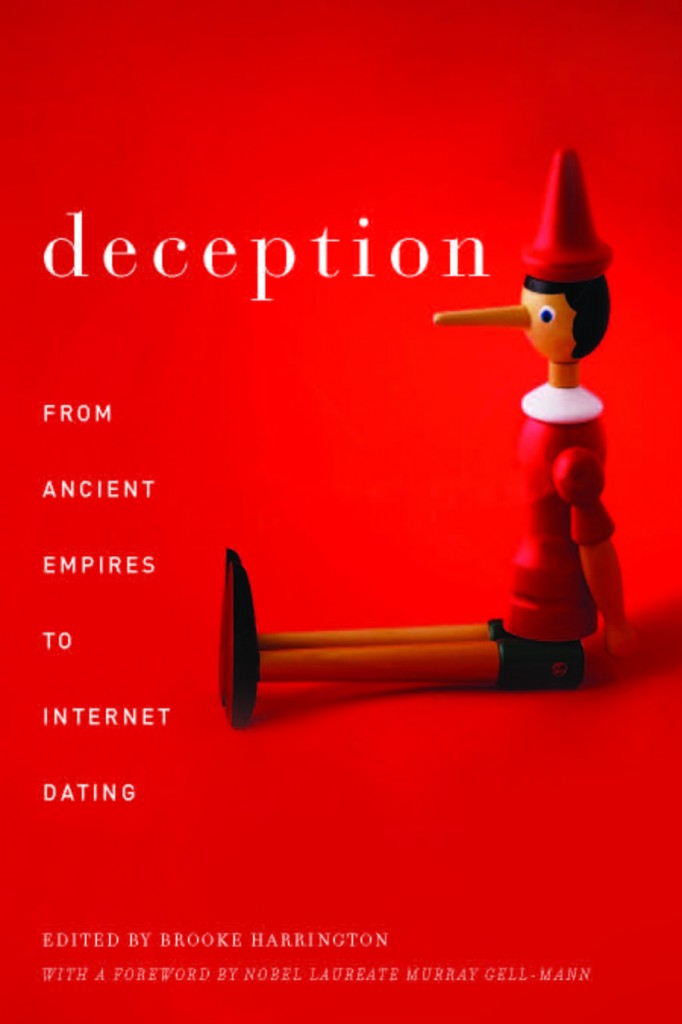

I know what you’re thinking when you see this photo: where can I get free samples of SPAM? Where is my priceless chunk of junk? Well look no further: I’m here to help.

I have to check the contents of my SPAM filter each and every day, because one time in 20, a legit message gets routed there by mistake. As a result, I get to read the subject lines of 50 or so emails, most of which are SPAM; some of them are so hilarious that I feel the need to memorialize them somehow. Here’s the catch of the day:

uplift your sweet couch experience : does this make it more likely that I’ll find change between the cushions? because if so, count me in!

Footjobs : this is probably a sly solicitation for nude toe modeling.

A Christian Sex Cure : only steely sociological discipline prevents me from clicking on this link; I would contact Max Weber in a seance just to hear what he could make of this one….

Sax can be endless! Im not kidding! : what about the rest of the brass section? what if the flugelhorns feel self-conscious? (P.S.: thanks to the sender of this email for noting that s/he is not kidding; because otherwise, I might have thought “no way can a saxophone be endless! this can only be a Dadaist provocation.”)

Do not worry about trifles , use new debilitant! : what is this “debilitant” of which they speak? I’m hoping it’s like the “neural neutralizer” from Men in Black, because I’ve got a lot of commercial jingles and songs from 1970s AOR floating around in my brain, and the lyrics to “Get Down Tonight” need to make way for things like the difference between Type I and Type II errors:

…I’d even settle for Buck Rogers’ “disintegrator.”

Just to add to the joy, living in Europe means that I now get SPAM in four languages: English, German, French and Italian. To my surprise, instead of showing cultural variations in the content of their wares, they all seem to be shilling the same things: sex, drugs and academic credentials. That last one kind of surprised me, because it would seem to appeal to a very different kind of customer–the academically insecure or ambitious?–than the ones for Viagra and various potions designed to increase (selectively) the size of our appendages.

Given the sociological evidence linking educational attainment to lifetime earnings, I suppose the diploma mill SPAM should be classified under “get rich quick” schemes, along with those helpful “stock tips” that were very common a few years ago. “Stock tip” SPAM seems to have declined precipitously in the last year, at least in my inbox, perhaps because the global market crisis means that when it comes to the stock market, everyone just wants out.

The other notable absence is the 419 or Nigerian bank scam emails. You know the ones: they usually open with an elaborately formal greeting, like “Most Esteemed Sir,” and then continue in this stilted prose–as though the writer had learned English from reading the lesser novels of Charles Dickens–to solicit “urgent help” in stashing a few million dollars in return for a percentage of the funds. This might be because all the publicity that 419 scams have received in the past five or six years has made people less likely to fall for them; or perhaps the world has just run out of fools.

Okay, perhaps that latter speculation stretches the bounds of credulity, but it is an empirical question whether there is a finite audience for these sorts of scams. Recent research is suggestive in this regard: in 2008, computer scientists from UC-Berkeley and UC-San Diego sent out a bunch of “fake SPAM” (how postmodern is that?) purporting to offer prescription drugs online; then they simply counted the number of responses they received.

“After 26 days, and almost 350 million e-mail messages, only 28 sales resulted,” wrote the researchers.

The response rate for this campaign was less than 0.00001%. This is far below the average of 2.15% reported by legitimate direct mail organisations.

“Taken together, these conversions would have resulted in revenues of $2,731.88—a bit over $100 a day for the measurement period,” said the researchers.

Another factor in the demise of the 419 scam is the rise of “web vigilantism,” in which groups like 419 Eater and Scam-O-Rama make sport of stringing scammers along, causing them to waste loads of time and money chasing false leads. The intention is to impose costs on the senders of these scam emails, because the main economic problem with SPAM to date has been that it costs senders virtually nothing. Since they have nothing to lose, even the meagre .00001% return estimated in the UC study would be a meaningful payoff. Particularly in countries where $100/day is a princely sum–countries such as Nigeria, where per capita GDP was US$1,128 in 2007/2008, according to estimates from the United Nations.

Still, if the UC study is correct, any downward pressure on the profits from the tiny proportion of responses that SPAM emails receive might be enough to change the cost-benefit ratio for the senders. The BBC News story concluded with the following sociologically intriguing observation:

Scaling this up to the full Storm network the researchers estimate that the controllers of the vast system are netting about $7,000 (£4,430) a day or more than $2m (£1.28m) per year.

While this was a good return, said the researchers, it did suggest that spammers were not making the vast sums of money that some people have predicted in the past.

They suggest that the tight costs might also open up new avenues of attack on spammers.

The researchers concluded: “The profit margin for spam may be meagre enough that spammers must be sensitive to the details of how their campaigns are run and are economically susceptible to new defences.”

Being “sensitive to the details” might include responding to the monitoring and sanctioning being conducted by web vigilantes. Read some of the stories on 419 Eater and Scam-O-Rama to see how scammers can spend days (and presumably significant sums of cash from their perspective) travelling to and fro in search of Western Union Moneygrams that have somehow been “misrouted” or money-toting messengers who never show for their appointments.

So it appears that there is some good news about SPAM: if profit margins are already razor-thin, as the UC study suggests, it may not be that hard to wipe them out entirely. On the more pessimistic side, I suspect that combatting SPAM in this way may just turn into a giant international game of Whac-a-Mole in which, as profits associated with certain genres of SPAM (like the 419, or online diplomas) asymptotically approach zero, those genres fade away, only to replaced by new ones.

Anyone want to guess what the next years hold for us in terms of SPAM come-ons? Human organs on the DL? Lots of money to be made there, but since eBay banned organ auctions in response to a fellow who tried to sell his kidney via their website, the transactions can’t happen via the legit online markets. So they stay underground, for now. But I wouldn’t be surprised if some of the market starts to bubble up into our SPAM filters. Think of this post when you get the first “are you the guy who can’t produce urea? hre’s new liver 4 u!” email. Til then, feel free to post your predictions, or your favorite SPAM subject lines, in the comments.

Once upon a time, the phrase “The Lady or the Tiger?”–taken from an 1882

Once upon a time, the phrase “The Lady or the Tiger?”–taken from an 1882