Facebook has had a rough few weeks. Just as the Cambridge Analytica scandal reached fever pitch, revelations about Zuckerberg’s use of self-destructing messages came to the surface. According to TechCrunch, three sources have confirmed that messages from Zuckerberg have been removed from their Facebook inboxes, despite the users’ own messages remaining visible. Facebook responded by explaining that the message-disappearing feature was a security measure put in place after the 2014 Sony hack. The company promptly disabled the feature for Zuckerberg and other executives and promised to integrate the disappearing message feature into the platform interface for all users in the near future.

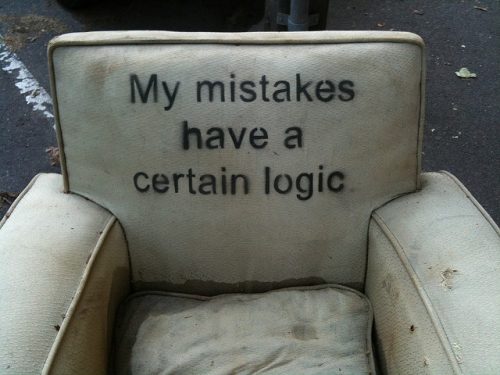

This quick apology and immediate feature change exemplifies a pattern revealed by Zeynep Tufekci in a NYT opinion piece, in which she describes Facebook’s public relations strategy as a series of public missteps followed by “a few apologies from Mr. Zuckerberg, some earnest-sounding promises to do better, followed by a couple of superficial changes to Facebook that fail to address the underlying structural problems.”

In the case of disappearing messages, Facebook’s response was both fast and shallow. Not only did the company fail to address underlying structural issues, but responded to the wrong issue entirely. Their promise to offer message deletion to all Facebook users treated the problem as one of equity. It presumed that what was wrong with Zuckerberg deleting his own messages from the archive was that others couldn’t do the same. But equity is not what’s at issue. Of course users don’t have the same control over content—or anything else on the Facebook platform—as the CEO. I think most people assume that they are less Facebook-Powerful than Mark Zuckerberg. Rather, what is at issue is a breach of accountability. Or more precisely, the problem with disappearing messages on Facebook is that this violated accountability expectations. more...