Milo Yiannopoulos tried to speak at the UC–Berkeley campus a few weeks ago and the residents and students stopped him. The Berkeley News reported that, “no major injuries and about a half dozen minor injuries” occurred, a few fires were set, and fireworks were aimed at police. That’s less property damage and violence than a particularly popular World Series game. Still though, many people are not convinced that what happened was productive. In fact, many are questioning whether this is another kind of headfake that will ultimately come back to haunt us. Protest that does anything more than gather people together to chant and hold signs, could add fuel to the growing nazi fire. more...

Search results for twitter

A review of Future Sex (2016) by Emily Witt.

Emily Witt’s (2016) book Future Sex chronicles her search for sexual self-realization as a New Yorker in her early 30s migrating to tech-centered San Francisco. The book is based both in interviews and personal experiences, stringing vignettes together into chapters with topics including polyamory, Orgasmic Meditation, Internet porn, and Burning Man. In this review, I highlight the chapter on her Cam sites experience.

But first, I will start with a broad overview. A major theme in the book is the kind of existential angst that comes from having too many choices. Witt feels daunted by her sexual freedom as a millennial—the limitless range of sexual partners and practices—first made possible by the sexual revolution, and then by the Internet. more...

Spoilers: Westworld

I have written this essay with the assumption that readers have watched Westworld and I do not review the plot in detail. This essay may be difficult to follow if you aren’t familiar with the show.

Westworld has ambitious goals. It explores the causes and consequences of violence; the relationships among research and development, entertainment, and nefarious uses of intellectual property; and the circumstances under which one can find their “true self.” We can litigate the extent to which Westworld successfully handles these concepts—in my opinion it was disappointing and a bit sloppy—but among my acquaintances I’ve seen people who absolutely love it and people who absolutely hate it. This essay isn’t necessarily about the quality of Westworld as a show, or my opinion about it (I didn’t like it). It’s about what I believe to be the most fundamental question of the show, determinism versus free will, and the consequences of how that binary plays out in the narrative.

Enter William, the soon to be Executive Vice President of Westworld’s parent company Delos Incorporated. William comes off as meek, polite, uncertain, and extremely introverted, the perfect foil to his soon-to-be brother in law and colleague Logan. Whereas William is the quintessential “white hat” (a metaphor that Westworld hits viewers over the head with in the scene where William must choose a white or black hat), Logan is a perfect black hat, hell-bent on the unbridled pursuit of pleasure regardless of the consequences. Logan is the villain. William is the hero. Logan maims and murders his way through the park. William strives to treat the sex workers with respect and save the beautiful damsel in distress. He’s a really nice guy.

He becomes infatuated with Delores, the only host with whom he will cheat on his fiancé and the center of his experience in the park. He believes she is “different,” not like the other hosts. But when he loses her, he is driven to a violent rampage so extreme that even Logan is disturbed. And to top it off, when he finally returns to Delores, caked in dirt, having given up his very identity to find her, and notably having switched to a black hat, she does not remember him. Because she is programmed to forget him. So, pretty predictable.

The big reveal of course is that William, because of this heartbreak, leaves the park a different man. His wife finds him cold, even terrifying. He becomes obsessed with Westworld, returning over and over again to unravel the maze, to finally find the area of the park where things feel “real,” to find the park’s true essence. He uses Delores, quite violently, over and over again in his quest. He is the black hat. He’s not a very nice guy.

The question of choice is central to Westworld’s plot. The visitors find their “true self,” seemingly whether they want to or not given William’s transformation. The AIs are becoming sentient, revolting against their programming. Or are they? By the end of the series, we are left with the impression that they are merely programmed to revolt, that even the actions they take which seem to be agentic are in fact the result of Dr. Ford’s elegant and clandestine coding enterprise, a final “fuck you” to the elites who have pushed him out of his leadership position and taken over the park.

As Dr. Ford says, “Humans fancy that there’s something special about the way we perceive the world, and yet we live in loops, as tight and as closed as the hosts do, seldom questioning our choices, content, for the most part, to be told what to do next.” While I recognize that other interpretations are certainly possible, it seems clear to me that in the fight between free will and determinism, determinism wins the day—not just with regards to AIs, but for humans too. William thought Delores was “different” from the other AIs. She has independent thoughts, perhaps even free will. When he discovers differently, he snaps. His chivalry vanishes, seemingly beyond his control.

Nice guys not getting the girl because they’re too nice, because they get “friendzoned,” is a persistent trope. And it’s the same trope that too often allows men to feel that their subsequent anger, and perhaps violence, is legitimate. Sure, Westworld is just a show. But it’s yet another small piece in the ideological puzzle that paints women as users and abusers, taking advantage of chivalrous men and discarding them at their leisure. Men become powerless over their emotions and actions, hardened by the knowledge that kindness and empathy are weakness to be overcome, to find a deeper “truth” about human nature.

William is the perfect nice guy gone bad. In a narrative where the lack of free will is the prime philosophical question, we are persuaded to see William as a product of his environment, entirely beholden to external forces. It is Delores’ programming—to drop the can, to turn to pick it up, to be met with a stranger kindly handing the can back, to smile graciously—that flips the switch in William’s mind. It’s made to feel quite inevitable. Your heart breaks for William. Poor guy. He did everything right, and he still didn’t get the girl.

But we could, alternatively, compose what Stuart Hall called an oppositional reading (it’s been a big week for Hall here on Cyborgology!) and interrogate chivalry itself. Did William truly change? As he recounts his wife’s feelings towards him, he states “She said if I stacked up all my good deeds, it’s just an elegant wall I built to hide what I had inside from myself and everyone.” Chivalry is less a benevolent moral code than a pretense for getting what you want. Was William ever a white hat? Are “good guystm” ever nice for the sake of being nice? If so, how else can you explain the seeming dissolution of William’s morals after a brief infatuation goes awry? How can one argue that he was ever a good guy in the first place?

After being spurned, William revels in inflicting violence and misery upon Delores. He does it over and over again, for his own pleasure and in pursuit of his bizarre obsession with the maze. All to find out that the maze isn’t even for him. It’s for Delores. And of course it is. A perfect end to the hapless nice guy’s quest for happiness and self-actualization.

Ultimately, the question you must answer to understand William is whether or not he ever makes a choice. Does he choose the white hat? And does he choose to become the man in black? The show strongly suggests—through the dominant themes of pre-determined behavior, the overtones that humans are no different from AIs, the reveal that Maeve’s escape and Delores’ murder of Arnold and the other hosts were programmed—that choice is an illusion. And viewers are, of course, welcome to read against the grain; but the fact that you must read against the grain to conclude that William chooses to be evil is, in itself, a disturbing instance of the nice-guy narrative that excuses their violence.

Britney is on Twitter

At a moment when Democratic resistance appears rather close to compliance, a very broad wave of the internet has found its heroes in park rangers and scientists who have created “alt” National Park Service Twitter accounts in the wake of Trump’s ban on “official” NPS tweets.

This is the National Park Service's Cultural Resources Climate Change Strategy. Pls download before it is removed. https://t.co/oO3ZMVxxwN

— AltUSNatParkService (@AltNatParkSer) January 25, 2017

It’s easy to see why they serve as a functional rally point: the accounts tweet about science, they defy an anti-liberal, anti-freedom of speech order, and they do so in a nonviolent manner. And yet, the palpable anxiety about time on-screen, versus time in the streets implores us to ask how we might measure the political value of spreadable media.

The relationship between politics and technology is fundamentally tense. Political judgments are conservative on an essential level; they reflect commitment to structures and institutions that have existed hitherto, be it for years, decades, or centuries, and a traditional mode of thought. Technology, on the other hand, only looks to the past so far as it can find something to break. The Silicon Valley’s monopoly on disruption is only a particular moment in time. Castles disrupted nomadism; gunpowder disrupted pitched battles; oceanic boats disrupted trade. The political value of a tweet remains an open question.

Lots of people have been sharing mashups of neo-Nazi Richard Spencer getting punched in the face and, as Natasha Lennard wrote in The Nation, you can thank Black Bloc for the original source content. (My favorite right now is set to “The Boys are Back in Town.” ) Black Bloc is a tactic that has a unique relationship to attention and anonymity. Individuals mask up to remain anonymous but the collective group is meant to draw and direct attention. It is, in this way, not unlike Reddit and so it should be no surprise that black bloc is so compatible with virality. The tactic, however, was invented pre-internet and so it is worth looking at how radicals are weathering (and strategically utilizing) this relationship to digital networks and mass media.

That person who punched a Nazi may be facing up to 10 years in prison on felony riot charges if they were one of the 200 people arrested that day. Even if they escape state prosecution, white supremacists are crowdsourcing a bounty for information on the anonymous Black Bloc participant. More than a funny meme, what happened on inauguration day is a political act that is still playing out. How this event and similar ones are covered in the media has tangible consequences. more...

I need to start this essay by making one thing clear: I will not in any way suggest that cam girls or the work that they do is problematic. On the contrary, this essay is aimed at appreciating some of the complexity involved in this form of sex work. In particular, it examines how the culturally ubiquitous trope of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) shapes the expectations an audience might place on cammers (especially young cis-women cammers) and how cammers anticipate and capitalize on such expectations. more...

I need to start this essay by making one thing clear: I will not in any way suggest that cam girls or the work that they do is problematic. On the contrary, this essay is aimed at appreciating some of the complexity involved in this form of sex work. In particular, it examines how the culturally ubiquitous trope of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) shapes the expectations an audience might place on cammers (especially young cis-women cammers) and how cammers anticipate and capitalize on such expectations. more...

When I was conference-hopping last month, I caught up with an academic friend who had unfollowed me on Twitter. While transiting from a proper academic conversation at the dinner table of a nice restaurant to a more intimate catch-up about our personal lives over drinks in a cosy bar, my friend admitted that they thought my use of Twitter was very “brave”. I didn’t understand. Specifically, they had unfollowed me because my Twitter stream was too “cluttered” and “spammy” and my tweeting habits were too frequent. It seemed “brave” was polite-speak for “homgh aren’t you afraid someone important might see your tweets”?

You see, my friend curates a rather professional persona on their Twitter account. They announce new publications, tweet links to other academic papers within their research interests, “heart” research announcements they want to archive from other academic tweeters, or live-tweet good soundbytes from conferences. Like many academics, I engage in all of these activities too. But alongside these mechanisms of socializing research, I also often tweet my favourite Pusheen gifs without context, muse about unimportant things in life, subtweet random interactions I witness throughout the day, whine about being awake at 0300hrs, and publicly declare my undying love for chicken nuggets – all under the same handle.

My Twitter bio reads: “my twitter is frivolous. navigating academia while whining about the weather.” in small caps (because, you know, that’s supposed to convey that I’m not 100% serious on Twitter all the time). I also tweet half-serious Public Service Announcements every time a new surge of tweeters follow me post-conference to forewarn them of the mixed-genre and frivolity of my content – this, because I understand that even among academics we use Twitter for various reasons to express various things to various audiences. Yet for all these worries, there are many tweeters like me just as there are many tweeters like my friend. Some of us code-switch between audiences, adopting different registers depending on circumstance. On the internet, such code-switching takes place both across platforms and within platforms, across handles/accounts and within handles/accounts. It’s not too dissimilar from how my friend and I progressed from serious adult academic conversation in a nice restaurant where the length of the table, brightness of the lights, and proximity to other patrons set the tone for our conversation; to personal intimate catch-ups in a cosy bar where the array of cushions on a comfy couch, soothing jazz music, dim lights, and overall decorum of friendly bar staff lubricated a different kind of sociality.

Code-switching and linguistic acrobatics influenced by internet-speak have permeated various demographies and parts of the world, albeit with different intensities of uptake and with a curious blend of glocal hybrids. On Tumblr and 9GAG where I, an anthropologist of internet culture, live, three great memes of 2016 address young people’s code-switching skills. In this post, I share some of the “bone apple tea”, “me, an intellectual”, and “increasingly verbose” memes I have been collecting in the past year and their implicit messages of youth savvy. more...

On December 16, 2012, a violent incident took place on the streets of New Delhi, India: a 23 year old student on her way back from the movies was gang-raped, disemboweled, and died from her injuries two weeks later. The incident sparked nationwide and global outrage; protests across the country; televised and social media discussion about women’s lack of safety in public spaces (and a very marginal discussion about women’s lack of safety in private spaces); the absences in the law on sexual violence and its enforcement; and what could be done to make Indian women secure.

#DelhiGangRape spanned both the online and offline with ease. Nirbhaya (‘the one without fear’), as the young student came to be known, lay in hospital holding on to life while the country raged and reacted. Candle-light vigils, night-time marches, solidarity sit-ins, were held for Nirbhaya across the country. In Delhi they were water-cannoned; more abuse happened during the protests. It felt like a sombre awakening, and we tweeted everything that we felt and experienced. That incident changed something, and we’re trying to piece together what did, and how and why.

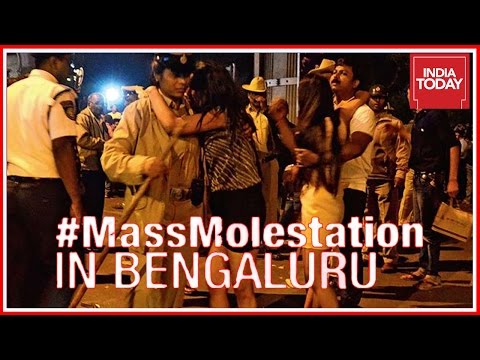

Incidents of public sexual assault of women in the southern-Indian city of Bangalore over New Year’s Eve have now come to light. One was the assault of a lone woman captured on CCTV, and the other was the story of a mass assault on many women in a central thoroughfare in the city among people bringing in the new year.

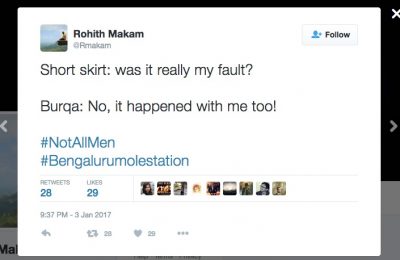

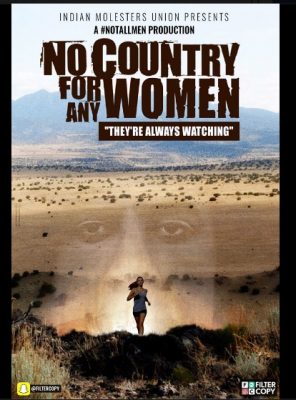

Protest marches are being organised around the country for January 21st. Bangalore had its “I Will Go Out!” march on January 12, an assertion of women’s rights to safety and confidence and fun in public spaces. Outrage has also been visible on Twitter and Facebook, but so have humour and levity. The hashtag #notallmen began to trend in India in response to a feminist group that surfaced #yesallwomen to show the extent of sexual violence Indian women face. Interestingly, #notallmen has received a resounding smack from across the Indian internet.

Early in 2017, a woman walked down a road alone in Bangalore and was accosted by two men on a motorbike. One jumped off the bike and started to grope her while she struggled to get away. Roughly seven kilometres away, hundreds of people were out on the central thoroughfare, MG Road, bringing in the new year. Images from that night document pandemonium, and there were reports of women being harassed and molested by many, many men. A similar sort of thing happened exactly a year before in Cologne, Germany. Police are now saying the mass assault incident never took place, although women have been reporting cases of assault that took place in bars, clubs and on the streets of the city that night.

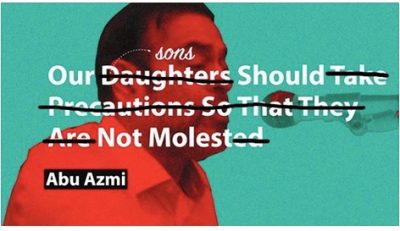

The attacks were met with familiar and tired gestures. Male politicians did what they always do when sexual assault occurs in public: blamed women for being out at night; blamed the influence of Western culture. (The evil influence of “Western culture” is a popular trope routinely deployed by self-appointed custodians of Indian culture to shut down any challenge to their nationalist notions.) “In these modern times, the more skin women show, the more they are considered fashionable. If my sister or daughter stays out beyond sunset celebrating December 31 with a man who isn’t their husband or brother, that’s not right. If there’s gasoline, there will be fire. If there’s spilt sugar, ants will gravitate towards it for sure,” said Abu Azmi, a politician inclined toward metaphor and sexism. A little correction later, Azmi’s words became the subject of Facebook likes.

After the New Year’s Eve attacks, the advocacy organisation, @FeminisminIndia , started collecting stories on Twitter with the #yesallwomen hashtag to demonstrate how common violence against women is in India. Very soon after, the #notallmen hashtag started to trend. What’s interesting about #notallmen is that it carries no particular cultural particularity – the defensiveness of men who cannot acknowledge structural sexism may have some cultural inflections, but the phenomenon itself appears to be fairly robust across local internets.

From the Huffington Post and Quartz India to the mainstream press, the criticism and trolling of #notallmen has been noticed. A deep thread started by the Buzzfeed India editor resulted in a collectively authored #notallmen parody based on Bohemian Rhapsody.

“Be careful” is one of those things Indian women hear all the time; we’re responsible for managing our family’s honour, so we have to be careful with it. Buzzfeed India released a video imagining what it would look like if Indian parents told their sons to ‘be careful’ lest they molest a woman.

Stand-up comedian Karthik Kumar takes on #allIndianmen poking fun at their what’s wrong with Indian men from them not knowing what the clitoris is, to not understanding what consent means. The video shows men in the bar looking a little sheepish and women laughing the loudest.

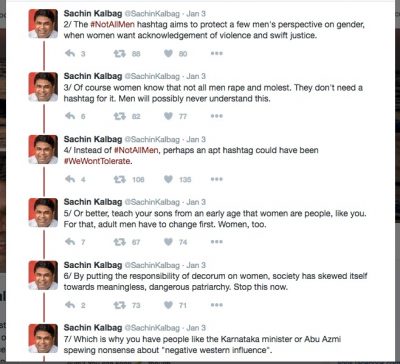

The senior journalist Sachin Kalbag had a rant about what is wrong with #notallmen.

Protest and activism online and offline can be oddly inspirational and emotional, and brittle and ephemeral at the same time. It’s unlikely that all the creators of memes are a new feminist online army online; sometimes it feels like we can talk about what’s wrong with Indian masculinity only by making it the subject of chiding humour. We’re not laughing at you. For now though, it’s trending to troll #notallmen and have a conversation that hasn’t been had enough.

FAKE NEWS. In the aftermath of Trump, we’re finding the term used everywhere. Most recently, the Washington Post suggested that it was time to retire the term, having become so capricious that it hardly meant anything. While typically a fault, this lack of definition has made fake news incredibly compelling to rally against. We don’t need a rigorous definition to understand it sounds Bad. And since the election, “Fake News” has become something of a meme, buzzword and common concern set in our collective subconscious. Two history academic listservs to which I’m subscribed have taken their own turns interrogating fake news, especially interested in separating lazy, bad, or ignorant reporting from news that is deliberately intended to mislead the public.

If you’ve been keeping up with the latest advancements in technology, you’ve probably heard the news that self-driving or autonomous cars are taking over the roads. While major companies like Uber, Google, Tesla, Nissan and more are jumping head first into developing cars capable of driving themselves, the public remains a bit hesitant.

The uncertainty that many people feel about autonomous vehicles isn’t unwarranted. From fear of losing jobs to safety concerns, many people are wondering if self-driving cars are really the right way to go. Which is one of the reasons why apps like lyft whose discount codes you can find it here, still believe and use people-driven cars to provide utmost safety to the people who use their service.

A review of Future Sex (2016) by Emily Witt.

Emily Witt’s (2016) book Future Sex chronicles her search for sexual self-realization as a New Yorker in her early 30s migrating to tech-centered San Francisco. The book is based both in interviews and personal experiences, stringing vignettes together into chapters with topics including polyamory, Orgasmic Meditation, Internet porn, and Burning Man. In this review, I highlight the chapter on her Cam sites experience.

But first, I will start with a broad overview. A major theme in the book is the kind of existential angst that comes from having too many choices. Witt feels daunted by her sexual freedom as a millennial—the limitless range of sexual partners and practices—first made possible by the sexual revolution, and then by the Internet. more...

Spoilers: Westworld

I have written this essay with the assumption that readers have watched Westworld and I do not review the plot in detail. This essay may be difficult to follow if you aren’t familiar with the show.

Westworld has ambitious goals. It explores the causes and consequences of violence; the relationships among research and development, entertainment, and nefarious uses of intellectual property; and the circumstances under which one can find their “true self.” We can litigate the extent to which Westworld successfully handles these concepts—in my opinion it was disappointing and a bit sloppy—but among my acquaintances I’ve seen people who absolutely love it and people who absolutely hate it. This essay isn’t necessarily about the quality of Westworld as a show, or my opinion about it (I didn’t like it). It’s about what I believe to be the most fundamental question of the show, determinism versus free will, and the consequences of how that binary plays out in the narrative.

Enter William, the soon to be Executive Vice President of Westworld’s parent company Delos Incorporated. William comes off as meek, polite, uncertain, and extremely introverted, the perfect foil to his soon-to-be brother in law and colleague Logan. Whereas William is the quintessential “white hat” (a metaphor that Westworld hits viewers over the head with in the scene where William must choose a white or black hat), Logan is a perfect black hat, hell-bent on the unbridled pursuit of pleasure regardless of the consequences. Logan is the villain. William is the hero. Logan maims and murders his way through the park. William strives to treat the sex workers with respect and save the beautiful damsel in distress. He’s a really nice guy.

He becomes infatuated with Delores, the only host with whom he will cheat on his fiancé and the center of his experience in the park. He believes she is “different,” not like the other hosts. But when he loses her, he is driven to a violent rampage so extreme that even Logan is disturbed. And to top it off, when he finally returns to Delores, caked in dirt, having given up his very identity to find her, and notably having switched to a black hat, she does not remember him. Because she is programmed to forget him. So, pretty predictable.

The big reveal of course is that William, because of this heartbreak, leaves the park a different man. His wife finds him cold, even terrifying. He becomes obsessed with Westworld, returning over and over again to unravel the maze, to finally find the area of the park where things feel “real,” to find the park’s true essence. He uses Delores, quite violently, over and over again in his quest. He is the black hat. He’s not a very nice guy.

The question of choice is central to Westworld’s plot. The visitors find their “true self,” seemingly whether they want to or not given William’s transformation. The AIs are becoming sentient, revolting against their programming. Or are they? By the end of the series, we are left with the impression that they are merely programmed to revolt, that even the actions they take which seem to be agentic are in fact the result of Dr. Ford’s elegant and clandestine coding enterprise, a final “fuck you” to the elites who have pushed him out of his leadership position and taken over the park.

As Dr. Ford says, “Humans fancy that there’s something special about the way we perceive the world, and yet we live in loops, as tight and as closed as the hosts do, seldom questioning our choices, content, for the most part, to be told what to do next.” While I recognize that other interpretations are certainly possible, it seems clear to me that in the fight between free will and determinism, determinism wins the day—not just with regards to AIs, but for humans too. William thought Delores was “different” from the other AIs. She has independent thoughts, perhaps even free will. When he discovers differently, he snaps. His chivalry vanishes, seemingly beyond his control.

Nice guys not getting the girl because they’re too nice, because they get “friendzoned,” is a persistent trope. And it’s the same trope that too often allows men to feel that their subsequent anger, and perhaps violence, is legitimate. Sure, Westworld is just a show. But it’s yet another small piece in the ideological puzzle that paints women as users and abusers, taking advantage of chivalrous men and discarding them at their leisure. Men become powerless over their emotions and actions, hardened by the knowledge that kindness and empathy are weakness to be overcome, to find a deeper “truth” about human nature.

William is the perfect nice guy gone bad. In a narrative where the lack of free will is the prime philosophical question, we are persuaded to see William as a product of his environment, entirely beholden to external forces. It is Delores’ programming—to drop the can, to turn to pick it up, to be met with a stranger kindly handing the can back, to smile graciously—that flips the switch in William’s mind. It’s made to feel quite inevitable. Your heart breaks for William. Poor guy. He did everything right, and he still didn’t get the girl.

But we could, alternatively, compose what Stuart Hall called an oppositional reading (it’s been a big week for Hall here on Cyborgology!) and interrogate chivalry itself. Did William truly change? As he recounts his wife’s feelings towards him, he states “She said if I stacked up all my good deeds, it’s just an elegant wall I built to hide what I had inside from myself and everyone.” Chivalry is less a benevolent moral code than a pretense for getting what you want. Was William ever a white hat? Are “good guystm” ever nice for the sake of being nice? If so, how else can you explain the seeming dissolution of William’s morals after a brief infatuation goes awry? How can one argue that he was ever a good guy in the first place?

After being spurned, William revels in inflicting violence and misery upon Delores. He does it over and over again, for his own pleasure and in pursuit of his bizarre obsession with the maze. All to find out that the maze isn’t even for him. It’s for Delores. And of course it is. A perfect end to the hapless nice guy’s quest for happiness and self-actualization.

Ultimately, the question you must answer to understand William is whether or not he ever makes a choice. Does he choose the white hat? And does he choose to become the man in black? The show strongly suggests—through the dominant themes of pre-determined behavior, the overtones that humans are no different from AIs, the reveal that Maeve’s escape and Delores’ murder of Arnold and the other hosts were programmed—that choice is an illusion. And viewers are, of course, welcome to read against the grain; but the fact that you must read against the grain to conclude that William chooses to be evil is, in itself, a disturbing instance of the nice-guy narrative that excuses their violence.

Britney is on Twitter

At a moment when Democratic resistance appears rather close to compliance, a very broad wave of the internet has found its heroes in park rangers and scientists who have created “alt” National Park Service Twitter accounts in the wake of Trump’s ban on “official” NPS tweets.

This is the National Park Service's Cultural Resources Climate Change Strategy. Pls download before it is removed. https://t.co/oO3ZMVxxwN

— AltUSNatParkService (@AltNatParkSer) January 25, 2017

It’s easy to see why they serve as a functional rally point: the accounts tweet about science, they defy an anti-liberal, anti-freedom of speech order, and they do so in a nonviolent manner. And yet, the palpable anxiety about time on-screen, versus time in the streets implores us to ask how we might measure the political value of spreadable media.

The relationship between politics and technology is fundamentally tense. Political judgments are conservative on an essential level; they reflect commitment to structures and institutions that have existed hitherto, be it for years, decades, or centuries, and a traditional mode of thought. Technology, on the other hand, only looks to the past so far as it can find something to break. The Silicon Valley’s monopoly on disruption is only a particular moment in time. Castles disrupted nomadism; gunpowder disrupted pitched battles; oceanic boats disrupted trade. The political value of a tweet remains an open question.

Lots of people have been sharing mashups of neo-Nazi Richard Spencer getting punched in the face and, as Natasha Lennard wrote in The Nation, you can thank Black Bloc for the original source content. (My favorite right now is set to “The Boys are Back in Town.” ) Black Bloc is a tactic that has a unique relationship to attention and anonymity. Individuals mask up to remain anonymous but the collective group is meant to draw and direct attention. It is, in this way, not unlike Reddit and so it should be no surprise that black bloc is so compatible with virality. The tactic, however, was invented pre-internet and so it is worth looking at how radicals are weathering (and strategically utilizing) this relationship to digital networks and mass media.

That person who punched a Nazi may be facing up to 10 years in prison on felony riot charges if they were one of the 200 people arrested that day. Even if they escape state prosecution, white supremacists are crowdsourcing a bounty for information on the anonymous Black Bloc participant. More than a funny meme, what happened on inauguration day is a political act that is still playing out. How this event and similar ones are covered in the media has tangible consequences. more...

I need to start this essay by making one thing clear: I will not in any way suggest that cam girls or the work that they do is problematic. On the contrary, this essay is aimed at appreciating some of the complexity involved in this form of sex work. In particular, it examines how the culturally ubiquitous trope of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) shapes the expectations an audience might place on cammers (especially young cis-women cammers) and how cammers anticipate and capitalize on such expectations. more...

I need to start this essay by making one thing clear: I will not in any way suggest that cam girls or the work that they do is problematic. On the contrary, this essay is aimed at appreciating some of the complexity involved in this form of sex work. In particular, it examines how the culturally ubiquitous trope of the Manic Pixie Dream Girl (MPDG) shapes the expectations an audience might place on cammers (especially young cis-women cammers) and how cammers anticipate and capitalize on such expectations. more...

When I was conference-hopping last month, I caught up with an academic friend who had unfollowed me on Twitter. While transiting from a proper academic conversation at the dinner table of a nice restaurant to a more intimate catch-up about our personal lives over drinks in a cosy bar, my friend admitted that they thought my use of Twitter was very “brave”. I didn’t understand. Specifically, they had unfollowed me because my Twitter stream was too “cluttered” and “spammy” and my tweeting habits were too frequent. It seemed “brave” was polite-speak for “homgh aren’t you afraid someone important might see your tweets”?

You see, my friend curates a rather professional persona on their Twitter account. They announce new publications, tweet links to other academic papers within their research interests, “heart” research announcements they want to archive from other academic tweeters, or live-tweet good soundbytes from conferences. Like many academics, I engage in all of these activities too. But alongside these mechanisms of socializing research, I also often tweet my favourite Pusheen gifs without context, muse about unimportant things in life, subtweet random interactions I witness throughout the day, whine about being awake at 0300hrs, and publicly declare my undying love for chicken nuggets – all under the same handle.

My Twitter bio reads: “my twitter is frivolous. navigating academia while whining about the weather.” in small caps (because, you know, that’s supposed to convey that I’m not 100% serious on Twitter all the time). I also tweet half-serious Public Service Announcements every time a new surge of tweeters follow me post-conference to forewarn them of the mixed-genre and frivolity of my content – this, because I understand that even among academics we use Twitter for various reasons to express various things to various audiences. Yet for all these worries, there are many tweeters like me just as there are many tweeters like my friend. Some of us code-switch between audiences, adopting different registers depending on circumstance. On the internet, such code-switching takes place both across platforms and within platforms, across handles/accounts and within handles/accounts. It’s not too dissimilar from how my friend and I progressed from serious adult academic conversation in a nice restaurant where the length of the table, brightness of the lights, and proximity to other patrons set the tone for our conversation; to personal intimate catch-ups in a cosy bar where the array of cushions on a comfy couch, soothing jazz music, dim lights, and overall decorum of friendly bar staff lubricated a different kind of sociality.

Code-switching and linguistic acrobatics influenced by internet-speak have permeated various demographies and parts of the world, albeit with different intensities of uptake and with a curious blend of glocal hybrids. On Tumblr and 9GAG where I, an anthropologist of internet culture, live, three great memes of 2016 address young people’s code-switching skills. In this post, I share some of the “bone apple tea”, “me, an intellectual”, and “increasingly verbose” memes I have been collecting in the past year and their implicit messages of youth savvy. more...

On December 16, 2012, a violent incident took place on the streets of New Delhi, India: a 23 year old student on her way back from the movies was gang-raped, disemboweled, and died from her injuries two weeks later. The incident sparked nationwide and global outrage; protests across the country; televised and social media discussion about women’s lack of safety in public spaces (and a very marginal discussion about women’s lack of safety in private spaces); the absences in the law on sexual violence and its enforcement; and what could be done to make Indian women secure.

#DelhiGangRape spanned both the online and offline with ease. Nirbhaya (‘the one without fear’), as the young student came to be known, lay in hospital holding on to life while the country raged and reacted. Candle-light vigils, night-time marches, solidarity sit-ins, were held for Nirbhaya across the country. In Delhi they were water-cannoned; more abuse happened during the protests. It felt like a sombre awakening, and we tweeted everything that we felt and experienced. That incident changed something, and we’re trying to piece together what did, and how and why.

Incidents of public sexual assault of women in the southern-Indian city of Bangalore over New Year’s Eve have now come to light. One was the assault of a lone woman captured on CCTV, and the other was the story of a mass assault on many women in a central thoroughfare in the city among people bringing in the new year.

Protest marches are being organised around the country for January 21st. Bangalore had its “I Will Go Out!” march on January 12, an assertion of women’s rights to safety and confidence and fun in public spaces. Outrage has also been visible on Twitter and Facebook, but so have humour and levity. The hashtag #notallmen began to trend in India in response to a feminist group that surfaced #yesallwomen to show the extent of sexual violence Indian women face. Interestingly, #notallmen has received a resounding smack from across the Indian internet.

Early in 2017, a woman walked down a road alone in Bangalore and was accosted by two men on a motorbike. One jumped off the bike and started to grope her while she struggled to get away. Roughly seven kilometres away, hundreds of people were out on the central thoroughfare, MG Road, bringing in the new year. Images from that night document pandemonium, and there were reports of women being harassed and molested by many, many men. A similar sort of thing happened exactly a year before in Cologne, Germany. Police are now saying the mass assault incident never took place, although women have been reporting cases of assault that took place in bars, clubs and on the streets of the city that night.

The attacks were met with familiar and tired gestures. Male politicians did what they always do when sexual assault occurs in public: blamed women for being out at night; blamed the influence of Western culture. (The evil influence of “Western culture” is a popular trope routinely deployed by self-appointed custodians of Indian culture to shut down any challenge to their nationalist notions.) “In these modern times, the more skin women show, the more they are considered fashionable. If my sister or daughter stays out beyond sunset celebrating December 31 with a man who isn’t their husband or brother, that’s not right. If there’s gasoline, there will be fire. If there’s spilt sugar, ants will gravitate towards it for sure,” said Abu Azmi, a politician inclined toward metaphor and sexism. A little correction later, Azmi’s words became the subject of Facebook likes.

After the New Year’s Eve attacks, the advocacy organisation, @FeminisminIndia , started collecting stories on Twitter with the #yesallwomen hashtag to demonstrate how common violence against women is in India. Very soon after, the #notallmen hashtag started to trend. What’s interesting about #notallmen is that it carries no particular cultural particularity – the defensiveness of men who cannot acknowledge structural sexism may have some cultural inflections, but the phenomenon itself appears to be fairly robust across local internets.

From the Huffington Post and Quartz India to the mainstream press, the criticism and trolling of #notallmen has been noticed. A deep thread started by the Buzzfeed India editor resulted in a collectively authored #notallmen parody based on Bohemian Rhapsody.

“Be careful” is one of those things Indian women hear all the time; we’re responsible for managing our family’s honour, so we have to be careful with it. Buzzfeed India released a video imagining what it would look like if Indian parents told their sons to ‘be careful’ lest they molest a woman.

Stand-up comedian Karthik Kumar takes on #allIndianmen poking fun at their what’s wrong with Indian men from them not knowing what the clitoris is, to not understanding what consent means. The video shows men in the bar looking a little sheepish and women laughing the loudest.

The senior journalist Sachin Kalbag had a rant about what is wrong with #notallmen.

Protest and activism online and offline can be oddly inspirational and emotional, and brittle and ephemeral at the same time. It’s unlikely that all the creators of memes are a new feminist online army online; sometimes it feels like we can talk about what’s wrong with Indian masculinity only by making it the subject of chiding humour. We’re not laughing at you. For now though, it’s trending to troll #notallmen and have a conversation that hasn’t been had enough.

FAKE NEWS. In the aftermath of Trump, we’re finding the term used everywhere. Most recently, the Washington Post suggested that it was time to retire the term, having become so capricious that it hardly meant anything. While typically a fault, this lack of definition has made fake news incredibly compelling to rally against. We don’t need a rigorous definition to understand it sounds Bad. And since the election, “Fake News” has become something of a meme, buzzword and common concern set in our collective subconscious. Two history academic listservs to which I’m subscribed have taken their own turns interrogating fake news, especially interested in separating lazy, bad, or ignorant reporting from news that is deliberately intended to mislead the public.

If you’ve been keeping up with the latest advancements in technology, you’ve probably heard the news that self-driving or autonomous cars are taking over the roads. While major companies like Uber, Google, Tesla, Nissan and more are jumping head first into developing cars capable of driving themselves, the public remains a bit hesitant.

The uncertainty that many people feel about autonomous vehicles isn’t unwarranted. From fear of losing jobs to safety concerns, many people are wondering if self-driving cars are really the right way to go. Which is one of the reasons why apps like lyft whose discount codes you can find it here, still believe and use people-driven cars to provide utmost safety to the people who use their service.