Is technology – especially communications technology – a necessary component of contemporary fiction? This is the question posed by Allison Gibson in an excellent piece posted earlier this week; it shouldn’t really surprise most people that she comes down on the side of “yes”, but the question – and its implications – are worth some more serious consideration. Especially when one considers setting, or (I don’t love the term but it has a certain utility) “genre”.

Recently mentions of a new “real-time social feed” called App.net have been creeping into my Twitter feed. Just as the quietly simmering Diaspora and the running joke that is G+ were geared to seize on collective Facebook malaise, it seems App.net is trying to seize on some degree of unrest among Twitter users before taking on Facebook as well. In this case, App.net promises that “users and developers [will] come first, not advertisers”; in an era of “if it’s free, you’re the product”—remember that the much love/hated Facebook “[is] free and always will be”—App.net proposes to offer a Twitter-like social feed (and eventually a “powerful ecosystem based on 3rd-party developer built ‘apps’”) on a paid membership basis instead.

This piece is cross-posted on Microsoft Research New England’s Social Media Collective Research Blog.

In her recent post here on the Cyborgology blog, Jenny Davis brought the pervasive use of Facebook as a study site back into conversation. In brief, she argued that “studying Facebook—or any fleeting technological object—is not problematic as long as we theorize said object.” The take away from this statement is important: We can hope to make lasting contributions to research literature through our conceptual work – much more so than through the necessarily ephemeral empirical details that are tied to a time, a place, and particular technologies.

In this post, I want to give a different yet complementary answer to why it may be a problem if our research efforts are focused on a single study site. This is regardless of whether it is the currently most popular social network site or an already obsolete technological object. more...

I am really pleased to see academics tackling the problems of ineffective activism and capitalist oppression. Overcoming such large and complicated problems means trying out every tool in the tool shed. That is why Levi R. Bryant’s “McKenzie Wark: How Do You Occupy an Abstraction?” is so important. It is one of many efforts by academics to apply their reasoning to an active social movement. His recommendations are quite brazen. Bryant writes: “You want to topple the 1% and get their attention? Don’t stand in front of Wall Street and bitch at bankers and brokers, occupy a highway. Hack a satellite and shut down communications. Block a port. Erase data banks, etc. Block the arteries; block the paths that this hyperobject requires to sustain itself.” The ends that Bryant suggests are intriguing. They certainly demand bigger and better things from the Occupy movement, but the means by which he reaches these conclusions are severely problematic. I think they neglect to consider the full effects of such actions and I attribute this oversight to his choice of analytic tools: object-oriented ontologies, new materialism, and actor network theory.

Chick-fil-A has delicious waffle fries. So delicious. But before getting in to the content of this post, I should locate myself by stating that I have not purchased anything from this company in over a year, and I will never consume those warm checkered squares of potato-y goodness again. The reason for this (in case anyone has been living under a rock/in a dissertation shaped bubble) is that the company explicitly opposes same-sex marriage. I am explicitly anti-bigotry, and so I do not purchase food from Chick-fil-A

Okay, now I can theorize. more...

This is the complete version of a three-part essay that I posted in May, June, and July of this year:

Part I: Distributed Agency and the Myth of Autonomy

Part II: Disclosure (Damned If You Do, Damned If You Don’t)

Part III: Documentary Consciousness

Part I: Distributed Agency and the Myth of Autonomy

Last spring at TtW2012, a panel titled “Logging off and Disconnection” considered how and why some people choose to restrict (or even terminate) their participation in digital social life—and in doing so raised the question, is it truly possible to log off? Taken together, the four talks by Jenny Davis (@Jup83), Jessica Roberts (@jessyrob), Laura Portwood-Stacer (@lportwoodstacer), and Jessica Vitak (@jvitak) suggested that, while most people express some degree of ambivalence about social media and other digital social technologies, the majority of digital social technology users find the burdens and anxieties of participating in digital social life to be vastly preferable to the burdens and anxieties that accompany not participating. The implied answer is therefore NO: though whether to use social media and digital social technologies remains a choice (in theory), the choice not to use these technologies is no longer a practicable option for number of people.

In this essay, I first extend the “logging off” argument by considering that it may be technically impossible for anyone, even social media rejecters and abstainers, to disconnect completely from social media and other digital social technologies (to which I will refer throughout simply as ‘digital social technologies’). Consequently, decisions about our presence and participation in digital social life are made not only by us, but also by an expanding network of others. I then examine two prevailing privacy discourses—one championed by journalists and bloggers, the other championed by digital technology companies—to show that, although our connections to digital social technology are out of our hands, we still conceptualize privacy as a matter of individual choice and control. Clinging to the myth of individual autonomy, however, leads us to think about privacy in ways that mask both structural inequality and larger issues of power. Finally, I argue that the reality of inescapable connection and the impossible demands of prevailing privacy discourses have together resulted in what I term documentary consciousness, or the abstracted and internalized reproduction of others’ documentary vision. Documentary consciousness demands impossible disciplinary projects, and as such brings with it a gnawing disquietude; it is not uniformly distributed, but rests most heavily on those for whom (in the words of Foucault) “visibility is a trap.” I close by calling for new ways of thinking about both privacy and autonomy that more accurately reflect the ways power and identity intersect in augmented societies. more...

Just some of my favorite quotes from what I read this past week on tech&society:

“As people become brands, we expect not friendship from them but customer service”

“I’m left wondering why we’re typing so breathlessly, like we’re all skydiving into prom”

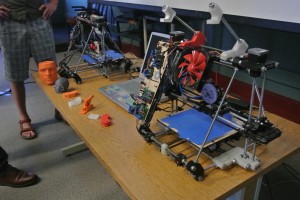

“Are 3D printers ontological white holes that produce reality from their printer heads?”

“TED is an insatiable kingpin of international meme laundering”

“drones are the most anthropomorphized of killing machines…so easily endowed with human subjectivity”

It’s become something like accepted common knowledge in the literature concerning barbarization in warfare that technology increases not only the scope and devastation of the nasty things that human beings are willing to do to each other, but the willingness of people to do those things.

Recently I’ve started to wonder if certain friends of mine aren’t receiving kickbacks from the social music streaming service Spotify. I’ve started calling these friends the “Spotivangelists,” and have jokingly insisted that recruitment bonuses are the only reason they could possibly have for being so intent on getting me to sign up. What I’ll try to examine in this post, however, is not why my friends are so intent on getting me to join Spotify, but why I’ve been so intent on resisting. By rights, I should be some kind of Spotifanatic; music is a huge part of my life, and I discover almost all of my new music through friends. So why am I still holding out?

The price of 3D printers is plummeting. Like all complicated pieces of technology it is quickly moving from large, confusing, and expensive to small, simple and cheap. This year has been full of consumer-level 3D printers that are cheaper than some professional grade photo printers. Right now, these little things are capable of making plastic do-dads that are, admittedly, of lesser quality than some dollar store toys. But just like a magic trick, you’re not paying for the physical thing, you’re paying for the ability to do the trick. Design an object in a modeling software suite like SketchUp, convert it into some kind of printer-friendly format, and -so long as it is smaller than a bread box and made out of plastic- you can build whatever you want. 3D printers give an individual the ability to transform bits into atoms. In some ways it is a radical democratization of the means of production. For a fraction of the price of a car, someone can gain the ability to fabricate a relatively wide range of material objects. What are the implications for this new ability? What does it say about the relationship of atoms and bits? more...