Wonderful new cover story from the New York Times Magazine about death on Facebook. Read it here.

Wonderful new cover story from the New York Times Magazine about death on Facebook. Read it here.

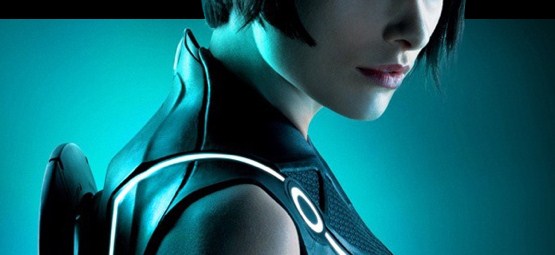

Yes, even a CGI-filled big-budget glowing Disney spectacle can provide opportunity for theorization. Of the recent Internet-themed blockbusters – namely, Avatar (2009); The Social Network (2010) – Tron: Legacy (2010) best captures the essence of this blog: that the digital and the physical are enmeshed together into an augmented reality.

This seems surprising given that the film is premised on the existence of a separate digital world. Indeed, the first Tron (1982) is all about a strict physical-digital dualism and the sequel plays on the same theme: physical person gets trapped in a digital world and attempts to escape. However, Tron: Legacy explores the overlapping of the physical and digital. The story goes that Flynn, the hero from the 1982 film, develops a digital world that does not have the imperfections of its physical counterpart. His grand vision was to gloriously move humanity online. Simultaneously, the beings in the digital world want to export their perfection out of the digital world and to colonize the offline world, removing all of its imperfections (i.e., us). Flynn comes to realize that enforced perfection (read: Nazism) is unwanted. Instead of a highly controlled and orderly universe, what has to be appreciated is what emerges out of chaos. And it is here that the film makes at least two theoretical statements that are well ahead of most movies and popular conceptions of the digital.

First is the tension between (1) top-down order and restricted information flows to create profit versus (2) generative spontaneity and the information-should-be-free ethic of what has come to be known as “cyberlibertarianism.” This is Web 1.0 versus Web 2.0, and the Tron sequel is fundamentally a Web 2.0 movie. The movie begins by showing a super-powerful software company overcharging for a stale product. One might be reminded of Microsoft here, and that fits, but what is more fitting is Apple. Apple exerts far more top-down control over their products and software, e.g. its walled-garden Apple Store. In fact, the software giant in the movie refers to their main product, an operating system, as simply “OS”, just as Apple does. This Web 1.0 software giant is the enemy in the physical-world and the enemies in the digital world are those who believe that information should be ordered and perfect. Instead, the heroes in the film are hackers who make the software available for free and believe that all information should be free. They believe in spontaneity and the generative power of chaos –the cyberlibertarian/hacker ethos of Web 2.0.

Second, the film updates the digital-physical dualism of its characters. In the 1982 version, one was either a digital “program” or a physical “user”; or as is the case of Flynn, a user transformed into something digital. The dualism remained strict. The purpose of this blog is, in part, to describe the ways in which the physical and technological and digital have all enmeshed together creating an augmented world occupied by cyborgs. And Tron: Legacy takes this directly into account by introducing revolutionary (and perhaps emancipatory) cyborg beings that are part digital and part physical –what Flynn (Jeff Bridges) describes as “bio-digital jazz, man.”

Second, the film updates the digital-physical dualism of its characters. In the 1982 version, one was either a digital “program” or a physical “user”; or as is the case of Flynn, a user transformed into something digital. The dualism remained strict. The purpose of this blog is, in part, to describe the ways in which the physical and technological and digital have all enmeshed together creating an augmented world occupied by cyborgs. And Tron: Legacy takes this directly into account by introducing revolutionary (and perhaps emancipatory) cyborg beings that are part digital and part physical –what Flynn (Jeff Bridges) describes as “bio-digital jazz, man.”

While The Social Network suffered from a severe misunderstanding of the Internet and social network sites specifically, Tron: Legacy seems to get it. Yes, the plot is weak and the dialogue is often cringe-worthy. However, one can instead focus on the theoretically-forward conceptual decisions that went into the film, to say nothing of the head-thumping Daft Punk soundtrack and the amazing neon head rush visuals that CGI was made for.

Via.

This post by Adriano Farano originally appeared on owni.eu on January 5, 2011.

The news that in 2010 Facebook overtook Google as the most visited website in the United States is absolutely astonishing. But one might wonder what meaning this has for the way we use the web today?

Facebook and Google seem to me the frontrunners of two separate conceptions of today’s Internet.

On one hand, Mountain View’s giant is the empire of the reason, the quintessence of what I would call the ‘cold web’. Google is used, deterministically, to search for something you are looking for. It can be extremely useful, though rarely exciting; we like it because its algorithms provide an order to the infinite data on the Internet. In this sense, Google is Apollonian. Like the Greek god of sun, light and poetry, later identified with order and reason, Google helps us to shed some light into the abundant mass of information available online.

On one hand, Mountain View’s giant is the empire of the reason, the quintessence of what I would call the ‘cold web’. Google is used, deterministically, to search for something you are looking for. It can be extremely useful, though rarely exciting; we like it because its algorithms provide an order to the infinite data on the Internet. In this sense, Google is Apollonian. Like the Greek god of sun, light and poetry, later identified with order and reason, Google helps us to shed some light into the abundant mass of information available online.

On the other hand, Facebook symbolizes the ‘hot web’. It is mainly used to keep in touch with our friends and beloved ones, or to satisfy our natural inclination towards voyeurism or other emotional interactions. Facebook may well become addictive, but its compulsive users are rarely proud of the amount of time they spend on it. Just like drinking or smoking, Facebook is more like a top vice of global society, rather than a service that solves our problems. That’s why Facebook is Dionysian. Like the Greek god of wine, later identified with irrationality, Facebook directly talks to our emotional side.

In a time when most platforms try to go social, the Apollonian and Dionysian concepts can be useful to understand the profound differences among them. Take LinkedIn. Isn’t it an Apollonian social network, mainly built to serve the need to manage your professional social life? Twitter is another good example. Because its corporate discourse defines Twitter as an ‘information network’ rather than a social network, this says a lot about its will to position itself within the field of the ‘cold’ exchange of information instead of the ‘hot emotions’ trade.

But the Apollonian/Dionysian one should not be regarded as a permanent dichotomy. In ‘The Birth of Tragedy’, Friedrich Nietzsche argued that the aesthetic primacy of ancient Greek tragedy came from the fact that the works of Aeschylus or Sophocles were able to marry both the Apollonian and the Dionysian.

In a sense, Google’s attempts to go social (e.g. with Buzz) and Facebook’s alliance with Bing to provide a social search experience may both be conceived as embryonic efforts to balance cold and hot, Apollonian and Dionysian. But in both cases the results are far from being successful so far. And Google and Facebook are still predominant in two well-defined and different areas.

The new Silicon Valley war may well be understood from this perspective, rather than with complicated and seldom accurate web metrics. A war which will be won by the first one among Google and Facebook who will be able to overtake the other’s core supremacy while defending its dominant positions.

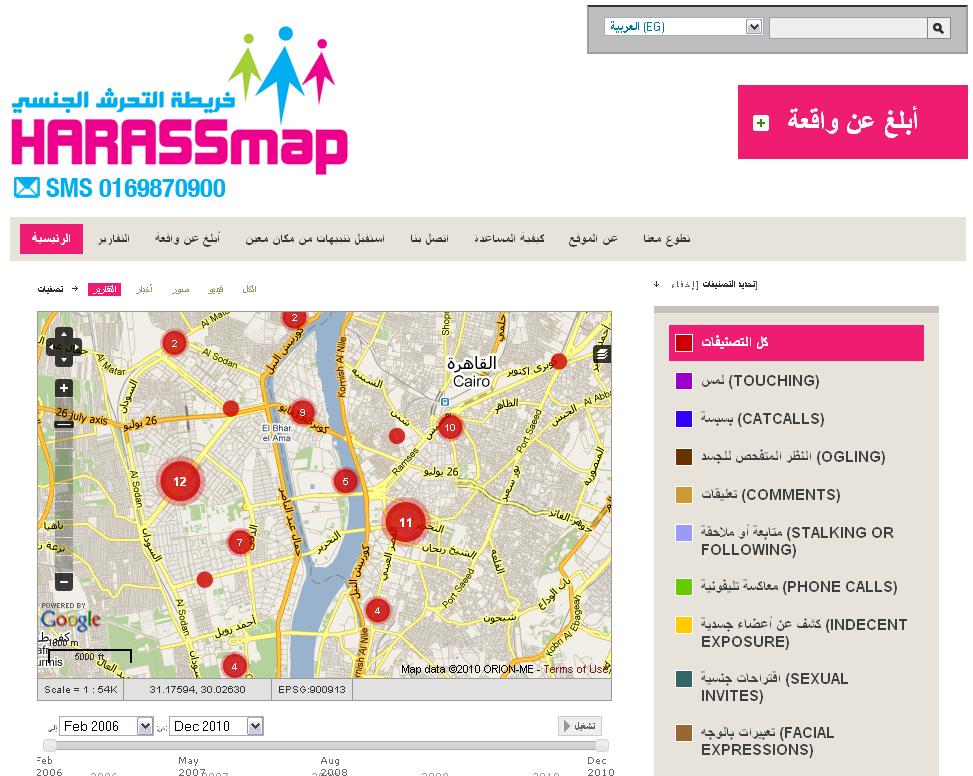

While many write about the various ways that the Internet makes us less safe, namely cyberbullying or being attacked by someone you met on Craigslist, it is also important to look at the new possibilities the web creates to ease suffering occurring in the physical world. When the Cyborgology editors recently spoke to WYPR about cyberbullying, we also discussed cybersupport, as is the case of Dan Savage’s It Gets Better YouTube project. The folks at WYPR also pointed us to another interesting example, the Egypt-based Harassmap created by a group of volunteer techno-activists. According to this report [.pdf], 83% of Egyptian women and 98% of female travelers to this country report being harassed. Given the very limited legal recourse for women in Egypt, this online tool is one way to provide voice to the vulnerable.

The map above is a screen-shot from the Harassmp site. Women in Cairo can report incidences of sexual harassment from their mobile phones via text message. The incident that occurred in the physical world is then digitized as a plot on the map using the phone’s GPS. This provides the masses a reality now augmented with a digital layer that seeks to “act as an advocacy, prevention, and response tool, highlighting the severity and pervasiveness of the problem.” The story of social media is not just how it harms people, but also how it helps.

View the map here. More information here (scroll down for English).

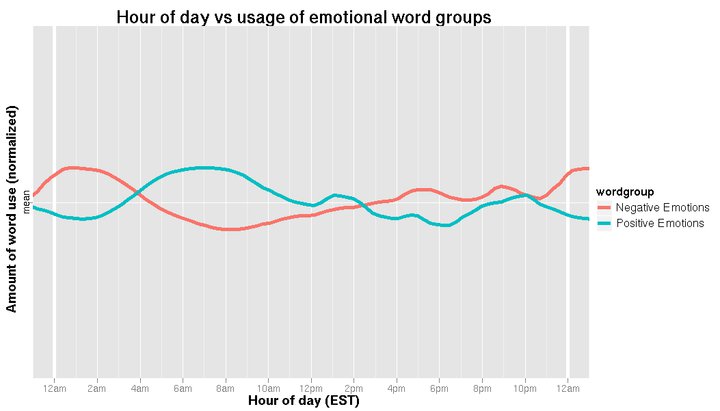

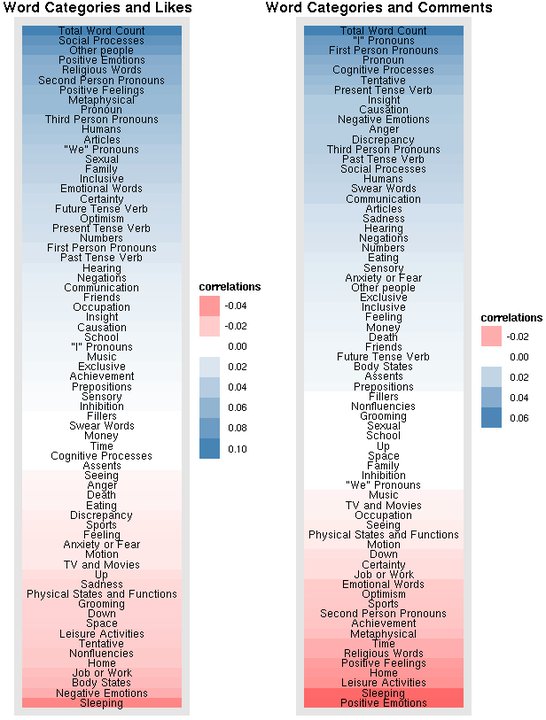

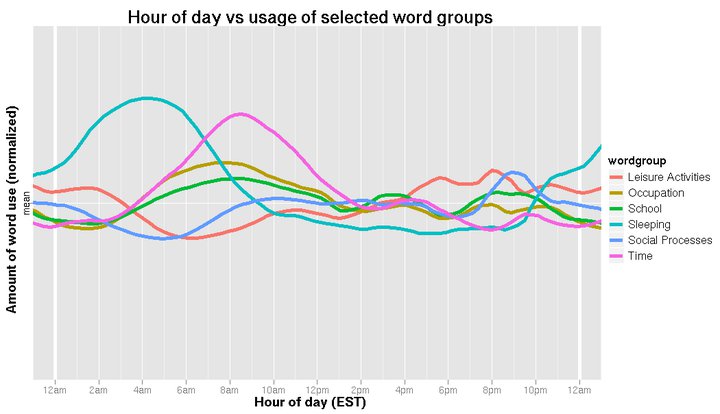

OK Cupid leads the way when it comes to providing analysis of user data in easy-to-understand charts and graphs. Facebook has done so less often, but provided some interesting new data last week. Lots of charts to dig into here. For instance, the types of topics that draw “likes” versus comments are especially interesting. Talk about religion and you’ll get lots of likes but few comments. Just the opposite for angry status updates which tend to garner lots of comments but few likes.

See all of the analysis here.

Should social media companies provide these quick-and-dirty, non-scientific and usually not all that well analyzed data on the web for all to see? The level of analysis is usually quite low (note that this Facebook data was posted by an intern for the site) and surely would not pass the peer review standards of a major social science journal. Are they doing a disservice by providing potential misinformation, or is this fulfilling a public duty to let us know a bit more about our own data?

The rant that anything digital is inherently shallow, most famously put forth in popular books such as “The Shallows” and “Cult of the Amateur,” becomes quite predictable. Even the underlying theme of The Social Network movie was that technology trades the depth of reality for the shallowness of virtuality. I have asserted that claims about what is more “deep” and “real” are claims to truth and thus claims to power. This was true when this New York Times panel discussion on digital books made constant reference to the death of depth and is still true in the face of new claims regarding the rise of texting, chatting and messaging using social media.

The rant that anything digital is inherently shallow, most famously put forth in popular books such as “The Shallows” and “Cult of the Amateur,” becomes quite predictable. Even the underlying theme of The Social Network movie was that technology trades the depth of reality for the shallowness of virtuality. I have asserted that claims about what is more “deep” and “real” are claims to truth and thus claims to power. This was true when this New York Times panel discussion on digital books made constant reference to the death of depth and is still true in the face of new claims regarding the rise of texting, chatting and messaging using social media.

Just as others lamented about the loss in depth when moving from the physical to the digital word, others are now claiming the loss of depth when moving from email to more instant forms of communication. E-etiquette writer Judith Kallos claims that because the norms surrounding new instant forms of communication do not adhere as strictly to grammatical rules, the writing is inherently “less deep.” She states that

We’re going down a road where we’re losing our skills to communicate with the written word

and elsewhere in the article another concludes that

the art of language, the beauty of language, is being lost.

There is much to critique here. Equating “depth” to grammatical rules privileges those with more formal education with the satisfaction of also being “deeper.” Depth is not lost in abbreviations just as it is not contained in spelling or punctuation. Instant streams of communication pinging back and forth have the potential to be rich with deep, meaningful content.

Second, the claim that instantaneity means a loss of ability to communicate seems to ignore the very fact that what we are seeing is an explosion of communication. We are not losing the “art” of language, as she says, but are seeing a proliferation of creative new ways to communicate. New slang, abbreviations, conversational norms and entirely new communication technology platforms are being invented and innovated by the second. Rather than the death of communication, we are seeing language and sociality do what it always does: evolve vibrantly and excitingly over time to adapt to, and also create, new realities.

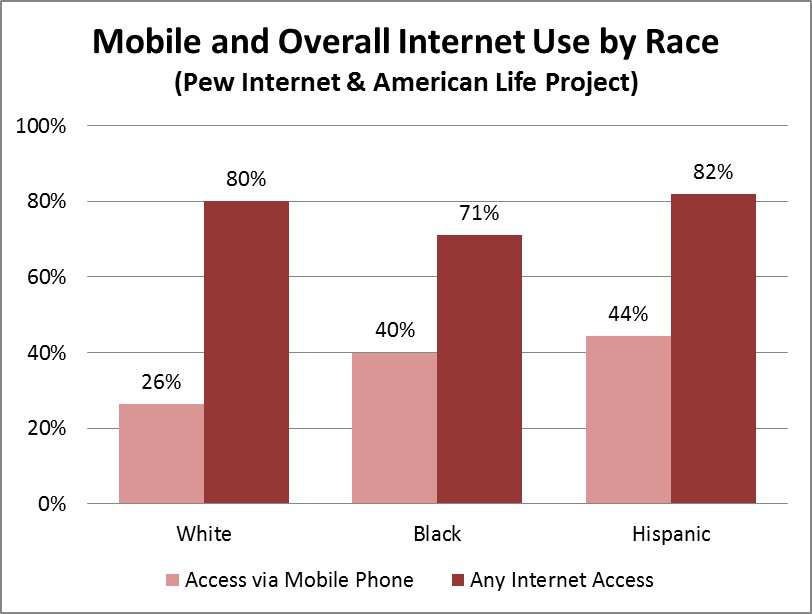

Ultimately, putting down ways of communicating foreign to you as inherently less deep, real and worthwhile is a claim to power. It is a way to reduce the ‘other’ as less fully human and capable. Particularity troubling in this case is the fact that nonwhites are overrepresented in these new, mobile communication technologies (especially Twitter). If one is to claim that instantaneity equals a lack of depth, one must also defend the implicit point that nonwhites utilizing new technologies to communicate in new ways are inherently communicating less deeply than their white counterparts. Who benefits from defining one way –their way- of interacting with information as deeper and more true?

Ultimately, putting down ways of communicating foreign to you as inherently less deep, real and worthwhile is a claim to power. It is a way to reduce the ‘other’ as less fully human and capable. Particularity troubling in this case is the fact that nonwhites are overrepresented in these new, mobile communication technologies (especially Twitter). If one is to claim that instantaneity equals a lack of depth, one must also defend the implicit point that nonwhites utilizing new technologies to communicate in new ways are inherently communicating less deeply than their white counterparts. Who benefits from defining one way –their way- of interacting with information as deeper and more true?

Life is rough for men wealthy enough to own an iPad: “how to carry it in a manner that is practical and yet, well, masculine.”

Life is rough for men wealthy enough to own an iPad: “how to carry it in a manner that is practical and yet, well, masculine.”

This is from a New York Times story that chronicles the danger of the iPad on a man’s masculinity, specifically, the need for a carrying case that does not look too much like –gasp!– a woman’s purse. The horror of appearing slightly feminine runs so deep that CNET ranks bags with a “humiliation index” (would be better to call it a “heteronormativity index”).

The story turns especially dark when we learn that Apple’s neglect has resulted in some men not being able to leave the house with their iPad. Or even worse, not buy one at all in fear of not appearing masculine enough. But there is hope for these rich males: “Scottevest plans to introduce an iPad-compatible blazer in time for Christmas.” See the manvertising here.

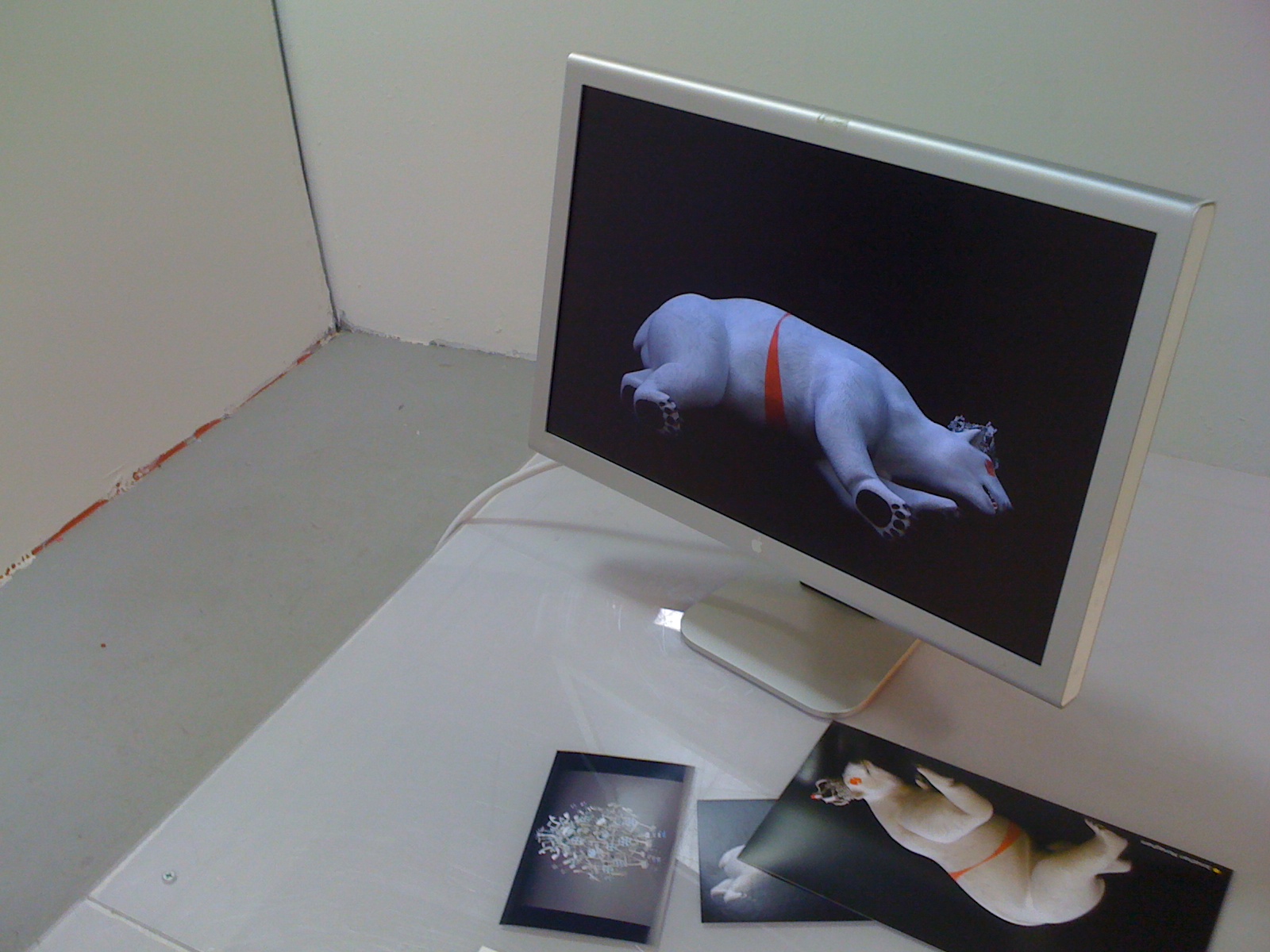

The Cyborgology editors dropped in on artist Jonathan Monaghan‘s studio to discuss his art and how it relates to technology and our contemporary world.

The impetus for my animation “Life Tastes Good” was seeing different depictions of polar bears on television. If they are selling soda, they are having a great time, if they are illustrating climate change, they are dying slow painful deaths. I decided to mix this disparate imagery into a new schizophrenic reality using the same 3d animation tools as those Coke commercials. These alternate digital realities I create in my work are both familiar and alien; playing with our desires, dreams and anxiety.

Jonathan Monaghan’s work is art in the age of hyperreality. Baudrillard offered hyperreality as a bloated, obese and dying environment liquidated of meaning, and here we see the simulated polar bear literally expiring on the screen. Monaghan has turned the simulated polar bear against itself by reintroducing it to the real.

More of Jonathan Monaghan’s work: