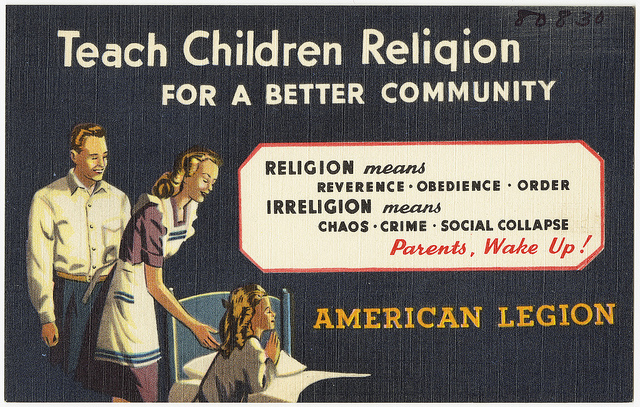

Sociologists Jamie Seabrook and William Avison’s research shatters the myth that children from single parent homes have worse outcomes than kids living with both parents. They told Northumberland Today that other factors better predict the future than whether a child lives with one versus two parents. “Instability really is the risk factor,” said Avison. “When there is a lot of transitioning in the family environment, that kind of instability doesn’t seem good for kids’ educational development and growing up to be adults.” They found that family structure had no impact on a child’s educational achievement or income, as long as the family structure remained consistent over time. When single mothers partnered and re-partnered several times, the researchers saw negative impacts on child outcomes compared to kids whose single mothers consistently single. Another interesting finding of the study is that children who grew up in stable single parent homes are less likely to divorce or separate than children who grew up in two-parent homes.

“The overarching conclusion is we have to be very careful saying the type of family you grow up in predicts kids’ success,” Seabrook said. Even if single parent homes are economically less advantaged than two-parent households, less money does not translate to differences in child education.