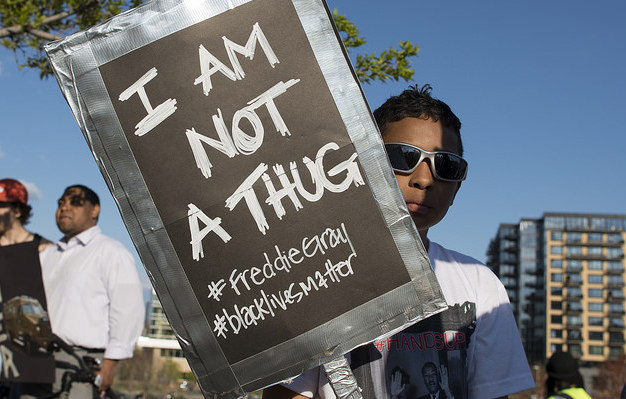

In February, PBS’s Independent Lens series aired “American Denial,” a documentary examining the powerful unconscious biases around race and class that still shape racial dynamics in the United States. The film largely focuses on Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal’s 1944 book An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy, comparing his findings about race relations in the Deep South during Jim Crow with more recent studies of racism and structural inequalities. Myrdal found that racism was not a “Negro Problem,” as his funders at the Carnegie Corporation of New York had told him, but a problem among whites perpetuating irrational fear of African Americans.

Among the many prominent scholars interviewed in the documentary is sociologist Sudhir Venkatesh, whose best-selling book Gang Leader for a Day took an in-depth look at racial inequality and poverty within Chicago’s most notorious housing projects. In the film, Venkatesh says of racism:

“It’s anything but a ‘Negro Problem.’ It’s a condition produced fundamentally by exclusion, racism, discrimination, and the unequal distribution of resources. I think it’s really hard to say we’re not actually doing much better on a lot of these questions about race, because the narrative is ‘America gets better every day.’ Well, what if it doesn’t?”

The film also recognizes earlier scholars of race including Frederick Douglass and sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois, noting that Myrdal’s work was given more recognition that Douglass and Du Bois’ because it came from a white European and was funded by the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

The documentary can be watched in its entirety here.