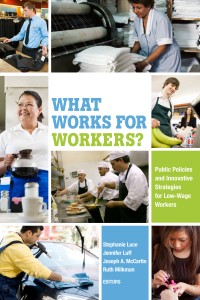

One of the most forceful themes in the 2015 State of the Union Address was the need to help working families. President Obama and other progressives argue that implementing policies like guaranteed paid sick leave and child care tax credits will boost the national economy by making it easier for mothers to work. Opponents believe the policies will hurt businesses, damaging job growth and economic recovery.

Sociologists have long studied how the roles of parent and worker intersect, and some of their data and findings are being put to use in this political debate. The New York Times’s Upshot blog highlighted several studies of paid leave policies, including CUNY sociologist Ruth Milkman’s work. Milkman’s analysis supports paid leave and credits for child care—she argues that “For workers who use these programs, they are extremely beneficial, and the business lobby’s predictions about how these programs are really a big burden on employers are not accurate.” Milkman, along with economist Eileen Applebaum, surveyed California firms about whether their costs had increased as a consequence of that state’s paid leave law. 87% of companies said that their bottom line had not suffered, and 9% found that their costs had actually decreased, thanks to lower worker turnover or health benefits payments.

Yet even in California, New Jersey, and Washington, the three states that have, thus far, enacted paid leave laws, many workers don’t know about the policies. State-level political campaigns may change policy, but a broader national discussion must help change workplace cultures to make good on the policies’ promise.