I attended my first healthy marriage education class with Christine and Bill, a white middle-class married couple studying to become marriage educators for their church. The first relationship skill we learned during our Mastering the Mysteries of Love training was the “showing understanding” skill focused on taking a partner’s perspective. Standing back-to-back, our instructor led us through an exercise during which Christine and Bill alternated describing what they saw in the classroom. Christine described the classroom white board. Bill described the other participants, tables, and chairs. “Is Christine wrong,” the instructor asked Bill, “because she sees the world differently than you? Now turn around. What do you see, Bill?” “I see what Christine saw,” he eagerly replied. This exercise was intended to teach us that learning to see things from our partner’s perspective was an important relationship skill that could revolutionize our love lives and improve our chances of having a happy, lifelong marriage. Bill later reported that developing this skill helped him understand Christine better and that he was falling in love with her all over again after decades of marriage.

I attended my first healthy marriage education class with Christine and Bill, a white middle-class married couple studying to become marriage educators for their church. The first relationship skill we learned during our Mastering the Mysteries of Love training was the “showing understanding” skill focused on taking a partner’s perspective. Standing back-to-back, our instructor led us through an exercise during which Christine and Bill alternated describing what they saw in the classroom. Christine described the classroom white board. Bill described the other participants, tables, and chairs. “Is Christine wrong,” the instructor asked Bill, “because she sees the world differently than you? Now turn around. What do you see, Bill?” “I see what Christine saw,” he eagerly replied. This exercise was intended to teach us that learning to see things from our partner’s perspective was an important relationship skill that could revolutionize our love lives and improve our chances of having a happy, lifelong marriage. Bill later reported that developing this skill helped him understand Christine better and that he was falling in love with her all over again after decades of marriage.

Two years later, I observed another healthy marriage class, this one for low-income, unmarried parents. There that day were Cody and Mindy, both 18 and white, who were struggling to make ends meet while raising their eight-month-old daughter and living in a studio apartment on money Cody made through his minimum-wage construction job. The communication lesson taught in this class—daily check-ins with one’s partner to understand their feelings and concerns—was similar to the one I learned in that first class with Christine and Bill. However, when Cody, Mindy, and I returned to class the following week, Cody shared that he found it difficult to practice what they’d learned. He and Mindy shared the studio apartment with several other people, making it hard to speak privately, and often fought about how they would spend their last few dollars—bus money or formula for the baby—until Cody’s next payday.

Focused on similar lessons about love in the context of widely varying social and economic circumstances, both classes had as their major goal the promotion of healthy marriage. Government funding for classes like these was first approved by Congress in 1996 when it overhauled U.S. welfare policy to promote work, marriage, and responsible fatherhood for families living in poverty. This led to the creation of the federal Healthy Marriage Initiative—often referred to as marriage promotion policy—which has spent almost $1 billion since 2002 to fund hundreds of relationship and marriage education programs across the country like the ones I attended with Christine, Bill, Cody, and Mindy. For three years, I observed over 500 hours of healthy marriage classes, analyzed 20 government-approved marriage education curricula, interviewed 15 staff who ran healthy marriage programs, and interviewed 45 low-income parents who took classes to answer the following questions: What does the implementation of healthy marriage policy reveal about political understandings of how romantic experiences, relationship behaviors, and marital choices are primary mechanisms of inequality? And, ultimately, what are the social and policy implications of healthy marriage education, especially for families living—and loving—in poverty?

My new book, Proposing Prosperity: Marriage Education Policy and Inequality in America, takes the reader inside the marriage education classroom to show how healthy marriage policy promotes the idea that preventing poverty depends on individuals’ abilities to learn about what I call skilled love. This is a romantic paradigm that assumes individuals can learn to love in line with long-term marital commitment by developing rational romantic values, emotional competencies, and interpersonal habits. By studying the on-the-ground implementation of healthy marriage policy, including training as a marriage educator for 18 government-approved curricula, I found that healthy marriage policy promotes skilled love as a strategy for preventing risky and financially costly relationship choices and, consequently, as the essential link between marriage and financial stability. Central to this message is the assumption that upward economic mobility is teachable and that romantic competence and well-informed intimate choices can help disadvantaged couples, such as Cody and Mindy, overcome financial constraints.

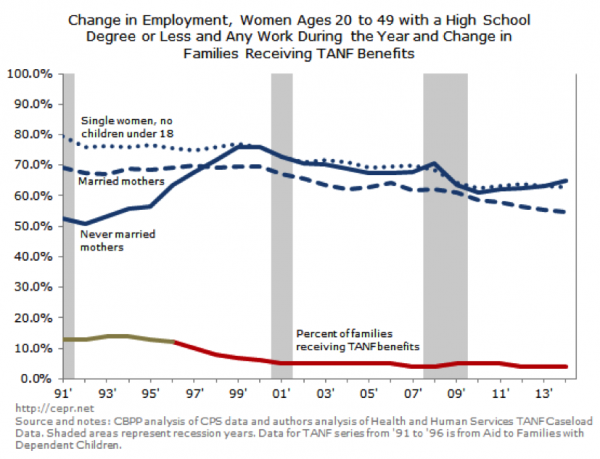

Healthy marriage policy assumes that developing relationship skills creates better marriages, which in turn lead to financial prosperity. However, the low-income couples I interviewed believed that marriage represents the culmination of prosperity, not a means to attain it. In the book, I describe how cultural and economic changes in marriage throughout the twentieth century have created a middle-class marriage culture in which low-income couples are less likely to marry for both ideological and financial reasons. Couples told me they could neither afford nor prioritize marriage until they were more financially stable. Their relationship stories illustrate how financial challenges lead to curtailed commitments, especially when marriage between two economically unstable partners seems like a financial risk. Marriage educators responded to this by deliberately avoiding talk of marriage and instead emphasizing committed co-parenting as the primary resource parents have to support their children.

Though parents frequently challenged instructors’ claims that marriage could directly help them, their children, and their finances, parents did find the classes useful. While low-income couples’ economic challenges made it hard to practice the skills, participants experienced the classes as a rare opportunity to communicate free of the material constraints that shaped their daily lives and romantic relationships. Hearing other low-income couples talk about their challenges with love and money normalized parents’ intimate struggles and allowed them to better understand how relationship conflict and unfulfilled hopes for marriage are shaped by poverty. This finding suggests that publicly sponsored relationship education could be a valuable social service in a highly unequal society where stable, happy marriages are increasingly becoming a privilege of the most advantaged couples.

Yet, low-income parents’ experiences with healthy marriage classes point to how relationship policies would likely be more useful if they focused more on how economic stressors take an emotional toll on romantic relationships and less on promoting the dubious message that marriage directly benefits poor families. I also show how the focus of healthy marriage programs on relationship skills obscures the insidious effects of institutionalized inequalities—specifically those related to class, gender, race, and sexual orientation—on romantic and economic opportunity. “Skills” were often an ideological cover for normative understandings of intimate life that privilege the two-parent, heterosexually married family. Marriage educators presented a selective interpretation of research that deceptively characterizes the social and economic benefits of marriage as a unidirectional causal relationship without accounting for how selection and discrimination shape the connection between marriage and economic prosperity.

What can policymakers learn from the experiences of low-income couples who took healthy marriage classes? Broader, sociologically informed relationship policies would recognize the benefits and costs of marriage and teach under what specific social and economic conditions marriage is typically beneficial. Any policy with the goal of promoting family stability and equality must contend with the intimate inequalities that lead to curtailed commitments. Programs that link economic prosperity with marriage will likely only reinforce couples’ tendencies to make marital decisions based on middle-class ideas of marriageability. The most effective policy approach to strengthening relationships and families will not be grounded in expectations of individual self-sufficiency and strategies—or skills—for interpersonal negotiation and understanding. Instead, it will reflect how love and commitment thrive most within the context of social and economic opportunity and equal recognition and support for all families as they really are, married and unmarried alike.

Jennifer M. Randles is author of Proposing Prosperity: Marriage Education Policy and Inequality in America (Columbia University Press, Publication Date: December 27, 2016). She is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology at California State University, Fresno. Her research explores how inequalities affect American family life and how policies address family-formation trends.

For all of its craziness and scariness, the 2016 election campaign has hammered home for millions of Americans the degree to which

For all of its craziness and scariness, the 2016 election campaign has hammered home for millions of Americans the degree to which