Hooray! Arielle Kuperberg is now to be the editor of CCF @ The Society Pages! Arielle has already populated many spaces in my life—mainly thanks to the interesting work she has done on cohabitation, hooking up, and most recently college debt. She’s been sharing her good research at The Society Pages and via mainstream media and sharpening (and debunking where necessary) some issues people hold dear. I asked Arielle a few questions about her thoughts about forward-facing scholarship as she begins this new role.

VR: You are a busy person, as a scholar, teacher, program director, and parent. In that context, can you tell us about your commitment to public sociology?

AK: I have long had an interest in the types of messages presented in the media, and the degree to which they are inaccurate. I was a media studies major in college before I switched to sociology, and one of my first publications examined media rhetoric surrounding stay-at-home mothers, and how this rhetoric did not match up with reality. After I went to grad school and began to publish more articles, I started becoming frustrated when I would see inaccurate or misleading things in the media that I knew my research could speak to, or contradicted. I was also frustrated that after all the effort of publishing articles on topics I felt were very important, very few people would read my research unless they happened to be doing research on the same topic. I had published articles on topics like the effectiveness of different policies in addressing poverty and gender/race-based pay inequality, and the role of poor labor market conditions in lowering marriage rates for the less educated, but what good did that work do if nobody ever heard of it?

When I was about to publish an article showing cohabitation does not cause divorce I felt this research was important enough that I should make a more concrete effort to get the word out, and that I was at a point in my career where I was ready to get more involved in public sociology. I got in touch with a mentor who recommended I get involved with the Council on Contemporary Families. CCF helped me put together a research brief about that project, and later another one about my research on college hookups, and both of those pieces were picked up by major outlets. I started writing some blog posts for the CCF blog and other blogs, and eventually started recruiting my friends into CCF and interviewing them for this blog, since they too have important research findings that more people should know about. Which is probably how I ended up in this position as the new editor.

I used to think of publication as the last stage in the “research pipeline” but I now think of public sociology as that last stage. For research to make an impact, other people need to hear about it. Academic research on the family has a lot to say about modern mythologies surrounding the family – but if nobody hears about it, it’s not going to be very useful. Pierre Bourdieu has been quoted as saying “My goal is to contribute to preventing people from being able to utter all kinds of nonsense about the social world” and I think that pretty well sums up my philosophy.

And yes I am extremely busy with all my different roles, but one of the reasons I went into academia is I enjoy the busyness and all the different roles you get to play – I’m never bored! I am also extremely lucky to have a partner who is a stay-at-home dad, and who supports my career by doing most of the heavy lifting when it comes to childcare and housework.

VR: Your active support of others’ work really stands out to me. What is your approach to mentoring, collaboration, and supporting colleagues and earlier career scholars?

AK: I am only in the position I am because of the generous mentoring of other people. My first two publications were coauthored with my undergraduate mentor Pamela Stone, who taught me everything from how to read a research article and format a table, to how to respond to reviewers when you get a “revise and resubmit.” She also introduced me to several leading scholars in the field when we went to conferences. Since then I have had several very important mentors who have helped me refine my research skills, wrote letters for me to get into grad school and later to get jobs, guided me through grad school, introduced me to their professional connections, gave me advice when I was facing important career decisions, and helped keep me going when I was facing various professional crises. I feel an obligation to pass that help forward to my students and junior colleagues, so that other people can have the same opportunities I had.

But it’s more than an obligation. I find mentoring to be one of the most rewarding aspects of being an academic. I’ve spent many years of my life developing some very specific skills in research, and some more general “succeeding in academia” skills, many of them learned the hard way. What use is all that knowledge if I keep it to myself? Plus there is a special kind of pleasure you get from seeing someone you mentored going off and doing well for themselves in life.

VR: What are your favorite ways of consuming social media?

AK: I have long been a fan of blogs. Back in 2001 when I was an undergraduate (and for several years afterwards), I started and ran a LiveJournal “community” (group blog) for sociologists, which was one of the earliest sociology blogs as far as I can tell. I think there is just something to be said about the short essay format that allows you to go more in depth than a tweet, but is still digestible in 10 minutes of reading while I’m drinking my morning coffee. One type of blog I particularly enjoy is the more personal memoir type of blogs, and I follow several non-academic blogs, although not as many as I used to.

Apart from that, I love facebook. I have made a few major moves in my life, and facebook lets me keep in touch with friends from the various places I’ve lived, and the academics I meet at various conferences. I also coordinate with two of my long-distance collaborators over facebook chat. I got a twitter account last year but have not used it as much as I could. I like the way it makes it easier to keep up with current events, and since most of the people I follow are academics and writers I have a very interesting feed, but I spend much more time on facebook. I also have participated in many message boards over the years, and right now my favorite one is reddit.

Arielle Kuperberg is an Associate Professor and Director of Undergraduate Studies in Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Follow her on twitter at @ATKuperberg. Virginia Rutter is Professor of Sociology at Framingham State University. Follow her on twitter at @VirginiaRutter.

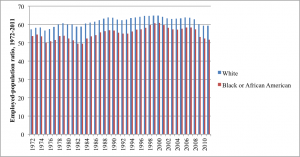

employed are

employed are

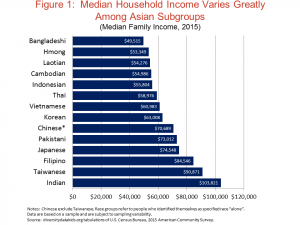

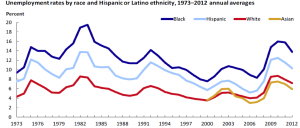

This fact sheet was compiled for the Council on Contemporary Families by scholars at

This fact sheet was compiled for the Council on Contemporary Families by scholars at

I attended my first healthy marriage education class with Christine and Bill, a white middle-class married couple studying to become marriage educators for their church. The first relationship skill we learned during our

I attended my first healthy marriage education class with Christine and Bill, a white middle-class married couple studying to become marriage educators for their church. The first relationship skill we learned during our