Nina Bandelj is Chancellor’s Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Irvine. She is an economic sociologist interested in how relational work, emotions, culture and power influence economic processes and has published widely, including in the American Sociological Review, American Journal of Sociology, Nature Human Behavior, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, Social Forces and Socio-Economic Review. She is the author of From Communists to Foreign Capitalists (2008) and Economy and State (with Elizabeth Sowers, 2010), and co-editor of Money Talks: Explaining How Money Really Works (with Frederick Wherry and Viviana Zelizer), among others. Bandelj served as President of the Society for the Advancement of Socio-Economics and as Vice-President of the American Sociological Association. She was a longtime and first woman editor of Socio-Economic Review and an inaugural associate vice provost for faculty development at UC Irvine. You can find Nina on Twitter @BandeljNina. Here, I talk with her about her new book, Overinvested: The Emotional Economy of Modern Parenting, published on January 20, 2026.

AMW: Your research shows that parents today treat children as both emotional treasures and financial investments. What did you learn about how this dual framing actually shapes day-to-day decisions about spending, saving, or even going into debt for their kids?

NB: What really struck me over the many years of research on this topic is how deeply the idea of investment has seeped into everyday parenting. What’s key is that “investment,” and “to be invested into something” has a revealing double meaning. Yes, it is about money, and parents need to pay ever escalating costs of childcare, of extracurricular activities, of college. But investment is also about emotion and identity: the belief that a good parent pours not just financial resources but their whole self into raising children.

We take it for granted that we need to be super invested to be good parents and forget that this hasn’t always been the case. For much of U.S. history, children contributed to the welfare of families, working on farms or through household labor. As Viviana Zelizer famously showed, the social value of children changed around the turn of the 20th century, from economically useful to emotionally priceless, as she called it. But today’s parents are tasked with taking an additional step: we are told we must invest in our precious children, especially their education, to build their human capital, as if children are assets that will appreciate and yield returns in adulthood. We have begun to treat children as investment projects.

In a country where schooling from preschool to college is enormously expensive, that imperative to build children’s human capital quickly becomes about financial resources. And many people assume that how parents save, invest, and yes, also borrow, for the sake of children is a matter of economic calculation. But when we talked to parents –my research team helped conduct 119 interviews– about what they do for their children, parents didn’t talk like economists about investments and returns. Rather, their narratives revealed how much they are devoted to their children and to being good parents. In this context, money has become a language of love. Parents do relational work, as economic sociologists would say, by using money of various forms (savings, expenditures, financial assets, and loans) to express care, commitment, and the kind of bond they want with their child. And it is “heartbreaking,” as one father said, “where the finances are such that you want something for the kids that you cannot afford to get.”

AMW: Across your interviews, you found that parents increasingly view parenting as the “most important job” and feel compelled to give their “entire selves” to it. What social forces most powerfully drive this sense of obligation, and how does it affect parents’ mental health and family well-being?

NB: What I appreciate about this question is that it lets us step back and see parents’ struggles not as individual shortcomings but as reflections of larger cultural forces. Parents we interviewed came from various socio-economic and racial backgrounds. We interviewed moms and dads, and they were of various religious and political dispositions. Still, our interviewees had something in common; they really wanted to do the best for their children. They took on parenting as the hardest but the most rewarding job, as many said.

But we should ask ourselves: why is raising children today financially and emotionally exhausting labor? We should ask this question especially after the pandemic challenges and after the U.S. Surgeon General pronounced the burnout and mental health of parents as a public health crisis in August 2024. In the book I explain that the understanding of parenting as a job is culturally produced and I identify two central social forces that contribute to it.

The first is what I call the rising dominance of the Economic Style, the spread of economic reasoning and influence of financial structures into areas of social life. We have seen this larger phenomenon in the economy and public policy that Elizabeth Popp Berman documented in her recent book, Thinking Like an Economist. What I show is that parenting hasn’t escaped these trends. Through the influence of economists, demographers, developmental psychologists and policy makers, childhood is understood as a development project. Children are treated as investment projects, where every learning activity, enrichment opportunity or school choice becomes a way to optimize investment.

The second equally powerful social change is the rise of the Emotional Style, or a therapeutic culture that urges us to use emotions as moral authority and center how we feel about ourselves and others. An explosion of parenting advice, given by experts but also coaches, popular psychology and social media, constantly disciplines a parent, telling us what we should be doing. And it also channels our focus on children’s emotional well-being, and to how we feel as parents. This means that today’s exhausting parenting reality is as much about parenting—what you do for your child—as it is about parenthood—who you are as a parent.

AMW: One of the most consequential findings in the book is that parental overinvestment—financial, emotional, and time-intensive—ultimately harms children, parents, and society. Based on your data, what specific mechanisms lead overinvestment to produce these negative outcomes?

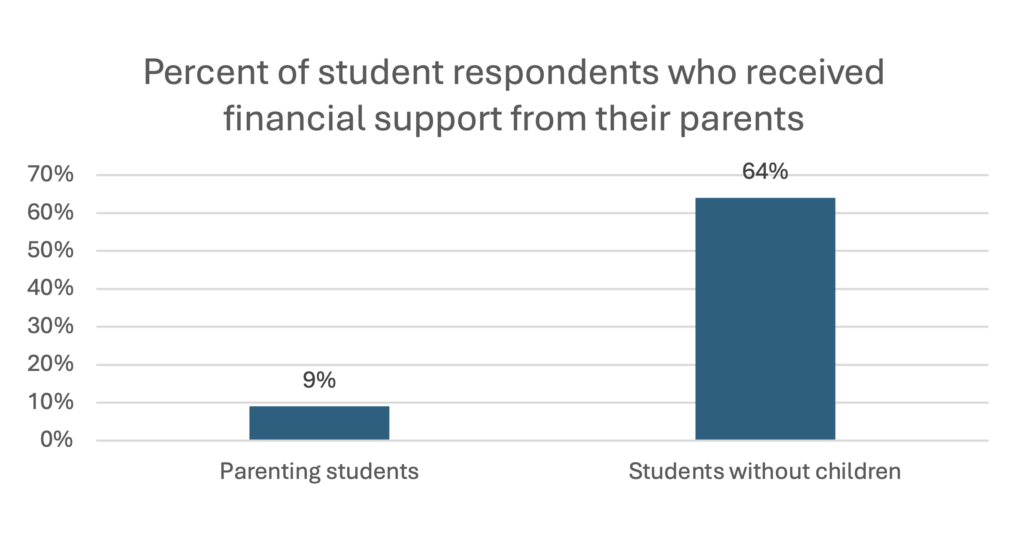

NB: During the pandemic, there was a lot of discussion about stressed out parents. The New York Times offered a “primal scream” phone line for “a parent who’s tired as hell” to call and scream after the beep. What Overinvested shows is that parental exhaustion, both emotional and financial, didn’t suddenly appear because of the pandemic. The pandemic exposed a system already stretched to its breaking point. And while I mentioned cultural changes as culprits, it is important to emphasize how interconnected they are with the U.S. political system that has not budged on a very family unfriendly policy and, what I call, privatization of childrearing. This means that having to bear the increasing financial pressures—because that’s what’s considered good parenting—has starkly unequal consequences for American families with different income and race backgrounds. The evidence from quantitative analyses based on the data from the Survey of Consumer Finances, Consumer Expenditures Survey and Panel Study of Income Dynamics documented in the book shows that wealthier families accumulate financial assets for children, including in 529 tax-advantaged education savings plans, while lower- and middle-income families increasingly rely on debt, especially mortgage debt to reside in good school neighborhoods and on education debt taken on disproportionately by Black families.

What’s the bottom line? Parenting today doesn’t just reproduce social inequality, as pointed out by an influential study in early 2000s by Annette Laureau on concerted cultivation of the well-to-do who pass on advantages to their children by imparting cultural capital. The new standard of (over)invested parenting seriously deepens economic and racial disparities among American families.

And this is in addition to strong evidence of parental burnout mentioned above, and in addition to now well-documented negative consequences of overinvolved/overmanaged parenting for children’s well being. Indeed, in so many ways the modern emotional economy of parenting is in crisis and, as one book reviewer pointed out, it’s high time to face this “urgent reckoning for American parents.”

Alicia M. Walker is Associate Professor of Sociology at Missouri State University and the author of two previous books on infidelity, and a forthcoming book, Bound by BDSM: Unexpected Lessons for Building a Happier Life (Bloomsbury Fall 2025) coauthored with Arielle Kuperberg. She is the current Editor in Chief of the Council of Contemporary Families blog, serves as Senior Fellow with CCF, and serves as Co-Chair of CCF alongside Arielle Kuperberg. Learn more about her on her website. Follow her on Twitter or Bluesky at @AliciaMWalker1, Facebook, her Hidden Desires column, and Instagram @aliciamwalkerphd