Friends are important because they help us when we are in need, they make us feel supported, and they make happy events even more enjoyable by sharing those good times with us. Fortunately, almost everyone knows how to make friends with a new acquaintance – you look for common interests, you do nice things for the other person, you hang out with them by engaging in their favorite activities or sometimes by participating in mutually-enjoyable activities. You might help your new acquaintance by giving them advice when it is sought, by listening to them, or by sharing with them things they need or want. Often, just showing an interest in a person is an important step in building a bond of friendship with them.

For over twenty years our research team has been studying a particular kind of friendship, that between a stepparent and stepchild. Stepfamilies are a sizable portion of American families; in a 2011 Pew Center survey, 42% of respondents reported having at least one stepfamily member, and younger adults had more step-relatives than older ones, so the numbers will continue to grow. We have been studying stepparent-stepchild relationships because family clinicians and researchers suggest that stepparents’ ability to develop close bonds with stepchildren may be critical to the well-being of couple and family relationships in stepfamilies.

In our first study of what we called “affinity-seeking,” we examined 53 stepparents’ efforts at building friendships with their stepchildren by doing in-depth interviews with stepparents, their spouses, and stepchildren. We found that stepparents who purposefully made friends and tried to build close bonds with their stepchildren before remarriage, and who continued to maintain those bonding activities after remarriage, felt closer to their stepchildren and reported less conflicts. Stepparents who befriended stepchildren when they were dating, but then stopped after remarriage, were not as close with their stepchildren and had more conflicts. Perhaps not surprisingly, stepparents who never made efforts to build affinity with stepchildren had the most emotionally distant stepfamily relationships. We also found, in another in-depth study of dozens of young adult stepchildren, that stepchildren had to notice what their stepparents were trying to do and respond affirmatively to those affinity-seeking efforts; it was not enough for stepparents to try to build bonds, stepchildren had to recognize their efforts, interpret them in a positive way, and respond in kind. In addition, we learned that stepchildren believe that the initial efforts to build a bond are the stepparents’ responsibility, not theirs.

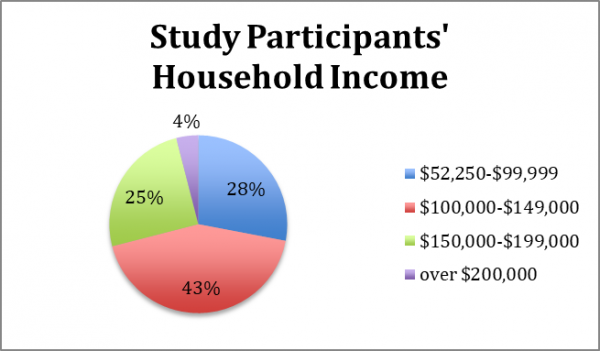

More recently, we gathered survey data online from 291 heterosexual remarried couples in which we asked them about stepparents’ affinity-seeking with stepchildren, marital quality, stepfamily conflict and cohesion. Information was obtained from husbands and wives separately, which allowed us to look at how stepparent affinity seeking related to both the stepparents’ and the biological parents’ perceptions about their marriage and family relationship quality. To assess stepparent affinity-seeking, we asked the partners individually to select the oldest child in their household who was from one of the partners’ previous relationships, and we asked them to think of that stepchild when responding to questions about stepparents’ efforts to build a friendship.

First, we explored factors related to stepparents’ efforts to befriend their stepchildren. Specifically, we evaluated how biological parents’ efforts at controlling stepparents’ interactions with their children (also known as “gatekeeping”) and stepparents’ self-perceptions of how they viewed close relationships with others (also known as “attachment orientations”) were associated with stepparents’ friendship-seeking behaviors with residential stepchildren. Stepparents who felt confident in their close relationships and, perhaps surprisingly, stepparents who felt anxious when interacting with others to whom they wanted to be close, engaged in more friendship- seeking behaviors with their stepchildren than did stepparents whose orientation was to keep their distance as a way to protect themselves in intimate relationships. We also found that both stepparents and their partners reported that the biological parents’ restrictive gatekeeping was strongly associated with fewer friendship-seeking behaviors by stepparents.

Next, we looked at whether the stepparent-stepchild relationship or marital relationship was more closely linked to overall stepfamily functioning. We did this because a researcher years ago had suggested that step-relationship quality was the most important predictor of stepfamily quality; some stepfamily therapists agree, while others contend that marital quality is key to family functioning. In our study we found that both relationships are important, although couples’ confidence in the future of their marriage was slightly more strongly associated with better stepfamily functioning (i.e., emotional closeness, communication, harmony) than was the quality of the stepparent-stepchild bond.

Finally, in a subsample of 234 stepfather-mother dyads, we found, after accounting for duration of mothers’ previous relationships, duration of the stepcouple relationship, the selected child’s biological sex and age, number of children in the household, and mothers’ report of household income, stepfathers’ perceptions of affinity-seeking with the child significantly predicted both partners’ perceptions of stepfather-stepchild conflict, marital quality, marital confidence, and stepfamily cohesion.

The results of these studies suggest that there are benefits associated with stepparent affinity-seeking – less conflict with stepchildren, better couple relationships, and closer stepfamily ties. Our findings provide evidence for encouraging stepparents to focus on building friendships with stepchildren. Our findings also illustrate that this is not always a simple thing to do. For these efforts to work, stepparents should engage in friendship-building behaviors early in the relationship and continue them as the bond builds. Additionally, the stepchildren must notice those efforts and respond affirmatively to them. Biological parents also need to allow opportunities for stepparents and stepchildren to engage with each other. When these things happen, then everyone in the stepfamily benefits. Stepparents and their partners (the parents of the children) need to think about this as an ongoing, long-term project – we found that some stepchildren disliked their stepparents and resisted any efforts to bond for some time, often months or years, before deciding that their stepparents’ efforts should be reciprocated.

Lawrence Ganong is an emeritus professor of human development and family science at the University of Missouri in Columbia, MO. Marilyn Coleman is a Distinguished Curator’s Professor Emerita of human development and family science at the University of Missouri in Columbia, MO. They have been studying stepfamily relationships for over 40 years.