A briefing paper prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families’ Symposium Parents Can’t Go It Alone—They Never Have.

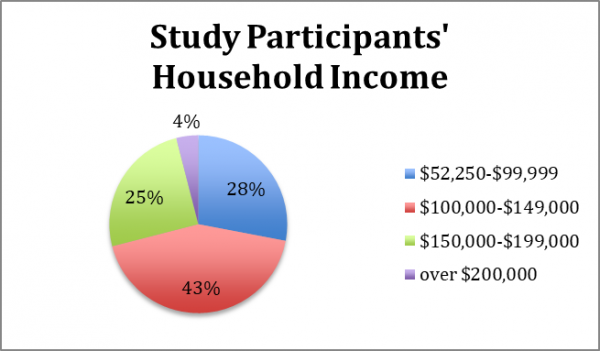

Who doesn’t want their children to grow up happy and healthy? But different families face different challenges. I interviewed 68 newly middle-class Latinx parents in Chicagoland, and learned that one of their pressing concerns is how to shield their children from the possibility of violence in their daily lives. Most people I interviewed were themselves the children of immigrants who had little education and worked low-wage jobs to support their families. This made my interviewees’ recently achieved middle-class status especially significant. They were able to raise their children in households with more than they had growing up. Three-fourths earned six figures. The majority were married couples where both parents worked for pay.

Optimism and Worry

Thanks to their upward mobility as adults, most interviewees reported feeling optimistic about raising their children. They had the money they needed, but could also transmit some knowledge and skills about how the United States worked. But these middle-class Latinx parents voiced serious concerns about the possibility of violence in their children’s lives, especially for their sons. They talked about the vulnerability of young men of color to all kinds of violence: gang-related violence perpetrated by other young men, gun violence, and violence at the hands of the police.

Latinx parents said they were worried because of what they see and had witnessed growing up in Chicago, especially how Black and Latino boys and men are disproportionately affected by the gun violence in the city. Local and national media coverage of shooting injuries and deaths in the city made them attuned to gun violence in Chicago. Chicago experienced an increased spike in violent crime rates in 2016, and 50 percent of shootings that year were concentrated in neighborhoods on the West and South sides of the city, such as Austin, North and South Lawndale, and Humboldt Park.

Neighborhood Advantage Isn’t Enough

Most of the people I talked to didn’t live in high-crime neighborhoods. Even so, the upwardly mobile Latinx parents in my study did not believe that their neighborhood choices could necessarily protect their sons from other forms of violence, such as racial discrimination.

Parents described some strategies they drew on to minimize the chances of their sons’ encounters with violence. They carefully chose where to live. Most of the Latinxs I interviewed lived in the city of Chicago, but a few lived in surrounding suburbs, citing gang and gun-related violence as a key reason for their decision to move. Yet those parents who lived in predominantly white suburbs understood that their sons ran the risk of being seen as a threat, particularly if they had dark skin tone. Just living in a suburb meant their sons could be racially profiled by police.

Latinx Parents’ Versions of “the Talk”

The suburban Latinx parents had to give their sons a version of “the talk.” They gave them specific instructions to help them reduce their vulnerability to police racism. These strategies centered on image and emotion management. They taught their sons to avoid oversized pants and shirts, not to cover their heads with hoodies while walking down the street especially at night, to make an effort to greet adults they met on the street, to avoid getting visibly angry or frustrated if questioned by other residents and police, and to follow directions if detained by police.

For parents who lived in the city, strategies to reduce the likelihood of sons’ exposure to violence included choosing city neighborhoods away from the West and South sides of the city. This strategy only went so far, however, because most parents did not think any neighborhood in Chicago was immune to violence. The parents in my study who did live on the West and South sides chose certain streets in their neighborhood that seemed to have less threat of violence and gang-related activities; they believed the threat of violence varied “block by block.” One father noted that it was possible for one neighborhood block to be generally “violent incident-free,” while the next had more crime, including gang-related physical assaults or gun violence. Parents who lived in the city described particular socialization strategies to protect their sons from violence. These were similar to those used by the suburban parents in my study, such as not appearing defiant or resistant when in contact with police. But these parents had other strategies as well, including teaching their sons which streets and/or street corners to avoid, restricting when and where they walked in the area, disallowing them to wear certain color combinations associated with gangs. They even taught them to be mindful of how to wear their baseball hats and to avoid hand gestures that might be mistaken as signaling gang membership to gang members or to police.

Although parents I talked to were especially worried about their sons’ vulnerability to violence, they also knew that their daughters were not exempt from gun violence or police brutality. Even so, their concerns for their daughters were more focused on sexual violence. They worried for sons because they were young Latino men, but worried for daughters as women vulnerable to sexual violence.

We won’t understand working parents unless we recognize this: All parents have concerns for their children’s safety, but what that means varies by race and class. Despite the economic privileges of reaching the middle class, the Latinx parents I talked to had serious worries about the risk of violence in their sons’ lives. These are stable two-parent families, where both parents work for pay; but they worry about how to keep their children safe when neither parent is around to enforce the rules that they believe will help their children avoid peer or police violence. They worry because no parent can be there around the clock to protect their children. Both academic and popular discussions of how families navigate the need to work outside the home should pay attention to what my research shows—that Latinx parents and other parents of color have additional worries. We need to realize that reducing violence in our cities and ending racism in our criminal justice system are policies needed to support working parents. No parents should have to worry when they go to work about their children experiencing violence.

Lorena Garcia, Associate Professor, is Director of Undergraduate Studies & Associate Head of Sociology & Latin American and Latino Studies, University of Illinois at Chicago, lorena@uic.edu.

Comments