In mid-March 2020, schools across the United States shuttered their doors. Kids were sent home and parents were expected to figure out how to work, supervise learning, and take on added caregiving and housework simultaneously. It’s no wonder parents are exhausted.

Initial hopes that schools would return to normal following summer break are now very much in question as rates of COVID-19 reached all-time highs just weeks before the anticipated start of public schools. Many school districts, including some of the largest in the country, have already made decisions to go fully remote in the fall. For working families in these districts, parents will once again juggle the competing demands of homeschooling and job responsibilities—all this as childcare centers are closed or operating on limited capacity and extended family care is limited to reduce the risk of exposure. We know that mothers already took on a larger share of childcare than fathers before the pandemic. Under these new conditions, it’s not surprising then that mothers’ employment has taken a serious hit.

A Work Crisis For Mothers

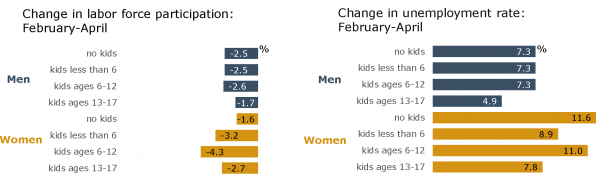

In a recently published study in Socius, we used data from the Current Population Survey to estimate just how much recent pandemic-related changes to family life have affected women’s and men’s employment outcomes. We compared a number of labor force estimates between February and April 2020, examining the period of time prior to the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S. to the height of the first wave when stay-at-home orders were issued across the country. We show that since February, labor force participation has dropped among mothers of younger children, while unemployment has risen dramatically. Mothers are also scaling back work hours among those with more flexibility to do so.

Data: Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS) Current Population Survey February and April 2020

Source: Liana Christin Landivar, Leah Ruppanner, William J. Scarborough, and Caitlyn Collins. 2020. “Early Signs Indicate COVID-19 is Exacerbating Gender Inequality in the Labor Force.” Socius 6:1-3. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120947997

Among married women employed in February, the labor force participation rate dropped by 4.3 percentage points by April, falling from 75.7% to 71.4%, for those with children ages 6 to 12. These children likely require more caregiving and remote learning supervision than teenagers. Labor force participation also fell among mothers of the youngest children (ages 1-5), declining by 3.2 percentage points. In all, nearly 250,000 more mothers than fathers with children under 13 left the labor force between February and April. Unemployment, up across the board, increased the most among childless women (11.6 percentage points) and mothers of young school-agers (11.0 percentage points), resulting in an April unemployment rate of 13.6% and 13.1%, respectively.

In another new study in Gender, Work & Organization, we show that mothers scaled back on work hours four to five times more than fathers over the same time period. Married mothers’ work hours declined by nearly two hours per week. Declines in hours worked were slightly larger among mothers of children ages 1-5 where both parents worked in occupations that allowed for teleworking. Most fathers’ reductions in hours worked were statistically insignificant. As a result, the gender gap in hours worked increased by 25% among all married, heterosexual couples and up to 50% among couples in occupations that allow telecommuting. This is a staggering reduction in work hours for mothers, leading to a dramatic increase in the gender gap in work hours over a short period of time.

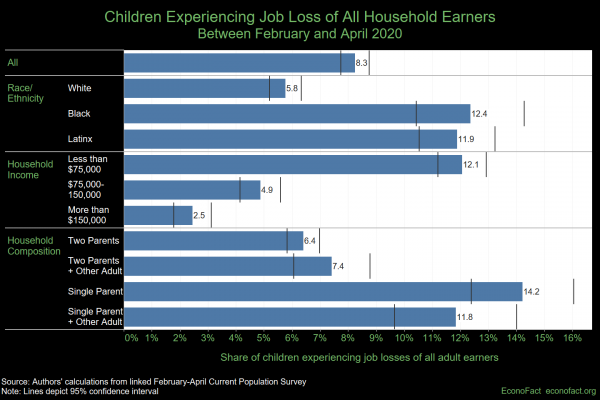

Policy Suggestions to Support Mothers’ Employment

The uncertainty of how long remote learning will continue and the lack of federal provisions to facilitate employment or help parents retain job attachment (e.g., though paid caregiving leave) may result in serious long-term effects for mothers’ employment who will be more likely to leave the labor force. Research shows that stepping out of the labor force for family reasons is stigmatized by many employers. As a result, mothers who leave work now may face barriers to re-entry later on. Reductions in employment as a result of the pandemic are likely to be steeper among Black and Latina mothers who are more likely to have to work onsite making simultaneous caregiving impossible in most instances, work in industries facing more significant disruptions, and are less likely to have flexible work options or paid leave.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) provided limited caregiving leave of up to 12 weeks for families who experienced school or childcare closures. However, the FFCRA exemptions by employer size and sector left millions of working parents without coverage. Removing the exclusions and expanding the amount of caregiving leave offered, as parents must now cover a new school year at home, would help parents retain attachment to an employer while taking leave to provide care or remote learning assistance to their children. Shoring up the childcare infrastructure—already weak in the United States—will be critical as childcare centers operate on slim margins and capacity restrictions may push many out of business. We have shown that subsidized childcare was critical to states’ economic recovery following the previous recession. Given the extreme pressure on families, we believe these resources are even more critical during this recession. Prioritizing the reopening of elementary schools would help families as children of this age have more intense childcare needs and are least able to learn effectively remotely. Finally, employers will need to continue to provide maximum flexibility to avoid significant turnover and loss of workers with caregiving responsibilities. Without proper supports, mothers’ employment may continue to drop, with lasting harmful effects to families’ economic security, gender and racial inequality, and national economic prosperity.

Liana Christin Landivar is a sociologist and a faculty affiliate at the Maryland Population Research Center, and is the author of Mothers at Work: Who Opts Out?. Follow her on twitter at @lclandivar. Leah Ruppanner is an Associate Professor of Sociology and Co-Director of The Policy Lab at the University of Melbourne and author of Motherlands: How U.S. States Push Mothers Out of Employment. Follow her on twitter @LeahRuppanner. William Scarborough is an Assistant Professor at the University of North Texas. Follow him on twitter @BuddyScarboro. Caitlyn Collins is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Washington University in St. Louis and author of Making Motherhood Work: How Women Manage Careers and Caregiving. Follow her on twitter @CaitlynMCollins