A briefing paper prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families’ Symposium Parents Can’t Go It Alone—They Never Have.

A briefing paper prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families’ Symposium Parents Can’t Go It Alone—They Never Have.

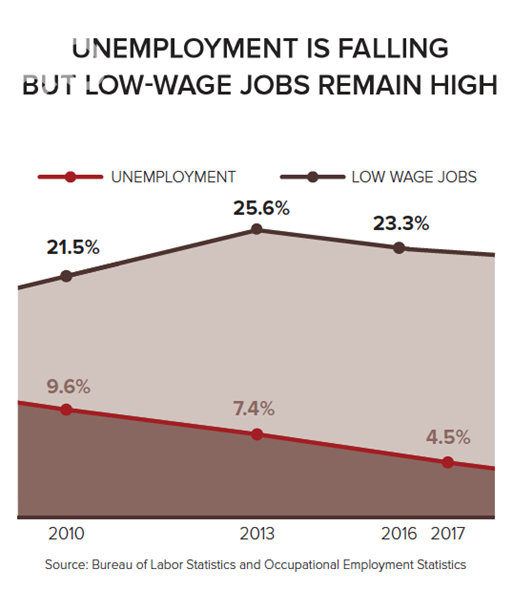

Low-wage jobs may not be anyone’s ideal for a career, but they are not going away anytime soon. The latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics shown (Figure 1) show that nearly one out of four Americans works for low wages. Many are parents. It is critical for the quality of family life in America that we understand how working conditions, including hours and flexibility, affect parents’ well-being, the quality of parenting, and, of course, the well-being of American children.

What are the problems for family life created by working conditions at low-wage jobs and what are some of the solutions to solve them? To understand what about low-wage work hurts families and what helps, we conducted interviews with 360 low-income, working families coping with new parenthood and old jobs.

Time was a theme that came up over and over again in our interviews with new parents. They talked about needing time to sleep, work, care for babies, connect with their partner, or simply to be alone. Parents also needed predictability in their time, meaning consistent and set hours. Parents with whom I talked also expressed the need for some control over their time, such as being able to make last-minute doctor appointments or take a needed sick day.

Parents need access to caregiving leaves, sick time, personal time, flexibility, and predictability—issues currently being addressed by policy initiatives across the country. But they also need better conditions of employment. In our efforts to support families by providing flexibility, predictability, and time away from work, we often overlook the impact of what happens during the 40+ hours per week spent “on the job.” Experiences on the factory floor, in the nursing home, or on food service lines that occur hourly, weekly, monthly, and year after year affect workers’ mental health, emotional well-being, physical health, stress, and energy. Such experiences can either enable or disable workers’ abilities to be engaged and sensitive parents. The question of how we “create” low-wage jobs that provide autonomy, meaning, and support requires listening to the workers themselves and understanding what about their work matters to them.

Recent interventions aimed at improving workers’ control over their schedules and enhancing supervisor support have shown that efforts to provide greater control and autonomy to workers produce better mental and physical health in workers and less employee turnover. But how control and autonomy might look in low-wage jobs is not obvious. My research suggests that what actually matters for low-wage workers is being able to take some initiatives and being recognized for doing so. For example, one woman I interviewed, Linda, who worked in a candle-packing factory as an order packer, reported extremely high levels of job autonomy. We learned that when she first started packing orders for customers, she would slip in some new candle scents with each order with a note to customers about how they might enjoy this new product. Slowly customers began to specifically request her services. Her boss recognized her creativity and “autonomy” and had her train new workers on how to connect with customers. She felt valued and respected for her work. Others parents have described autonomy at work as having their opinions valued and having a voice in decision making.

Conditions on the job affect workers’ mental health, and that affects their relationships at home. Having autonomy and some control at work translates into more engaged parenting at home: Parents are more involved with their babies and exhibit more responsive and sensitive parenting. Jose, a young father who works as a line cook at a steak house, talks about work as fun and energizing; his boss lets him try out new recipes, plan items for the menu, and learn more about budgeting. He works long hours for minimum wage, but feels valued and sees a career trajectory ahead of him. He wants to succeed now that he is a father. When Jose walks in the door at home he completely engages as a parent, holding his son, singing and laughing. It is a pattern we saw time and time again. We also saw the other side: parents working at jobs that are rigid, boring, and disempowering—experiences that can translate to disengaged or often harsh and insensitive parenting at home.

Often when we evaluate the effectiveness of a new policy in the United States, such as the current paid leave policies popping up in states across the country, we demonstrate its success by proving to employers or policy makers that there was no financial fallout from instituting this policy. What if—instead or in addition—we measured success by a reduction in working parents’ stress or in the improved well-being of parents and children? Or what about happiness? A provocative study by Glass, Simon, and Anderson found that parents in the United States report the lowest levels of happiness among the 22 OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries studied. We must continually solicit feedback from workers themselves about what policies and supports are most important to them. Their voices matter. Once a policy is instituted, we need to hear from them about the consequences. Did it help? Did it help some workers more than others? Should we try something new?

As we consider the solutions to better support working families in this country, it is easy to feel overwhelmed by the magnitude of the economic and social inequality. Many of us feel powerless, seeing solutions embroiled in the slow-moving wheels of policy and government action. Yet my data and those of others suggest that today each of us could create ways to improve workplaces and build cultures of respect and support that hold implications for workers and their families, especially their children. Such simple interventions as giving workers some control over day-to-day operations, soliciting their feedback, understanding the challenges they may face at home, and respecting their contributions are concrete ways to improve work settings. If we are truly invested in giving the next generation of children in this country a healthy and equal start, perhaps the first place to look is at workplace. Work matters.

Maureen Perry-Jenkins is Professor of Psychology and Director at Center for Research on Families at the University of Massachusetts, mpj@psych.umass.edu.

Comments