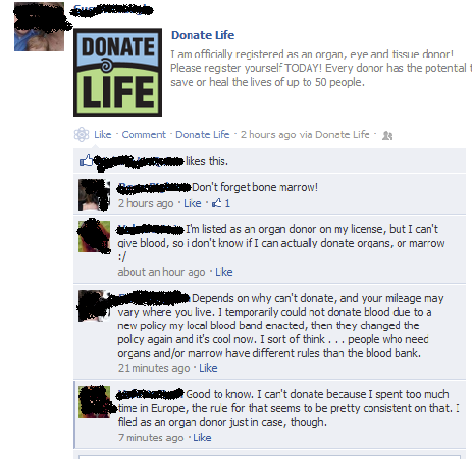

There is often the assumption that the information economy expects us to consume more and more, leading us to process more but concentrate less. Some have called this a “fear of missing out” (or FOMO), a “blend of anxiety, inadequacy and irritation that can flare up while skimming social media.” However, most of these arguments about FOMO make the false assumption that the information economy wants and expects us to always process more. This isn’t true; we need to accept the reality that the information economy as well as our own preferences actually value, even need, missing out.

Many do feel in over their heads when scrolling social media streams. Especially those of us who make a hobby or career in the attention/information economy, always reading, sharing, commenting and writing; tweeting, blogging, retweeting and reblogging. Many of us do feel positioned directly in the path of a growing avalanche of information, scared of missing out and afraid of losing our ability to slow down, concentrate, connect and daydream, too distracted by that growing list of unread tweets. While it seemed fun and harmless (Tribble-like?) at first, have we found ourselves drowning in the information streams we signed up for and participate in? more...