Note: This is half conventional Cyborgology post – if such a thing can be said to exist – and half explanation/personal apologia. It’s front-loaded with the latter. I usually assume it’s understood that when I have an opinion it’s not CYBORGOLOGY’S OPINION, all official-like, but I want to be very clear about that here for reasons that will become evident.

It seemed almost like fate, the way Vice’s tech blog Motherboard launched its new online science fiction short story magazine – somewhat ironically called Terraform – the day after nominations opened for the Nebula awards and all us SFF (science fiction and fantasy) writers were bemoaning the sheer amount of reading we all had to do to even have a prayer of being able to participate in the process.

Here’s why:

Science fiction is everywhere. It may be our most popular, and populist, of genres. We can’t seem to get enough of it in the multiplexes and on Netflix. But, weirdly, there’s a distinct dearth of science fiction in its purest, arguably its original, form—short fiction—in the environment to which it seems best-suited. The internet.

That’s the first paragraph from Terraform’s manifesto regarding why they exist (the rest of the text proceeded along the same lines until it was edited). It made people angry. Specifically, it made SFF short story writers and editors angry, and a dogpile ensued both on Twitter and in the comments, in which – full disclosure – I participated. I did so because I felt very strongly about why Terraform claimed to be doing what they were doing. A lot of us felt strongly. The reasons for this might not be evident to someone who isn’t embedded in the SFF community, and I want to talk about them, in part because I feel like they should be articulated but also because I think the whole thing serves as an interesting and instructive example of what happens not only when someone blunders into a community and proceeds to violate a bunch of its norms but, in fact, when someone blunders into a community and doesn’t seem to realize they’ve done so.

And it’s an example of how someone powerful can perpetuate harmful processes without knowing or intending to do so.

The most immediate problem with Terraform’s statement above is that it just flat-out isn’t true. Short SFF is going through a renaissance at the moment, and has been for a while – and the primary reason is the explosion of online short SFF fiction markets. Not only is there not a “dearth” of short SFF online, there is more of it – and more amazing stuff within it – than one could ever hope to keep up with. Yes, I’m obviously biased. I’m also right, in a literally quantifiable sense. And it was puzzling that Terraform appeared to not be aware of what it would have taken ten seconds and Google to know.

More than that, though, people were offended, and it’s this reaction that I think might have been most puzzling to outsiders. Why should a magazine feel obligated to acknowledge its “competitors”? Why would that be something they would want to do? As one commenter argued:

I would suggest that successful businesses entering new markets do not start their press releases by acknowledging the fine products already put out by their competitors who are already servicing their audience just fine. They start by exaggerating and saying there is a great need for their prduct(sic) and that they are going to change the landscape.

The problem there is something of which the commenter is apparently not aware, and Terraform also seemed to not know: Launching a fiction magazine – especially in genre – is not like launching a news magazine or even a topical blog. “Competition” in the capitalist free-market sense simply doesn’t apply. This is especially true in SFF in 2014, because of the tight-knit relationships this kind of digital publishing facilitates. Magazines don’t compete; they cross-promote. Editors send writers to each other and spotlight writers at other magazines. When nominations open for the Nebulas and Hugos, we all recommend stories to each other, from everywhere. Fiction writing is, by its very nature, a communal enterprise, and the bonds that hold that community together can be powerful, and governed by powerful norms. Terraform may have thought they were simply indicating that there was a need for what they were offering, but to the rest of us, to essentially state that reality wasn’t as it is was bizarre. It was bizarre, and to some it felt like a fairly pointed snub on the part of a newcomer.

One might not like that we got angry, but to be surprised is frankly naive. This is how communities work.

There’s an additional point of normative misunderstanding that I think played a role. The same commenter I quoted above articulated it pretty nicely:

The entirety of the people who are pissed off are the authors (and those that publish them). This announcement is for the readers, not the writers.

Okay, two things.

A) In the SFF genre, the line between “fan-reader” and “author” – and indeed “editor” – is so thin and porous as to be nonexistent. Most of us wear multiple hats. Authors frequently edit and vice-versa. And we all read. We are all fans. This is part of why:

B) The launch of a fiction magazine is going by its very nature to be for authors just as much as people who purely read. Whether or not Terraform intended or wanted this is irrelevant. Because we are hungry, and we are frequently poor. We don’t want to keep newcomers out; we want as many of them as possible, because we like to be paid. The more paying markets there are, the more money there is to go around. So we’re always watching, and when a new zine launches we’ll notice within seconds. Terraform launched with no submission guidelines and no stated pay rates, which – to us – is so strange as to be almost unthinkable. Many if not most new zines lead with guidelines and pay rates before they ever officially open their doors or announce the featured authors in their first issue.

This is because they want to attract authors. They want submissions. And they’re participating in the dynamics of a community. It’s a subtle but important signal to everyone else: We’re here, we’re engaged, we want to play. By neglecting to do this, Terraform’s introduction gave the impression to many of us that not only were they not engaged, but they weren’t aware we were here at all.

(Incidentally, Terraform has since announced they’ll pay twenty cents a word. That is staggeringly good. Had they led with that, I think we would have been willing to forgive them almost anything.)

But here’s the final – and to my mind, the most important and the most damaging – problem, and it’s one that exists entirely because there is so much short SFF online right now.

SFF has historically been very white, very straight, very cisgender, very Western, and very male. For a long time it’s been an uncomfortable place to be if you’re a member of any marginalized group. Not only has the overall atmosphere been toxic to a significant degree, but the doors have been solidly closed to marginalized authors. What the explosion of digital short SFF markets has done – in part – is start to change that. The barriers to entry for a professional-paying (at least six cents a word, as defined by the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America) short fiction market are by no means nonexistent, but they’re significantly lower than they would necessarily be if we were relying on print, and the reach of those markets is tremendously greater.

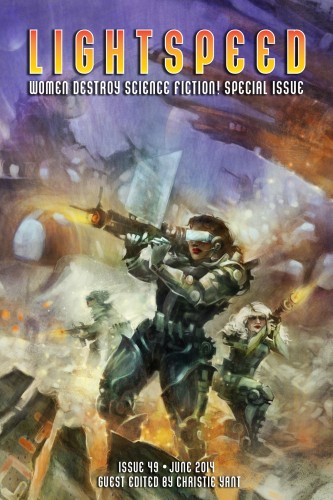

We’re using this advantage, and we’re using it actively. The majority of the professional digital short fiction markets have at least claimed that it’s their goal to find and promote marginalized authors, and many have done so. Strange Horizons – one of the oldest – has been doing it forever. Lightspeed, Clarkesworld, Apex, Tor.com, Shimmer, Nightmare, Daily Science Fiction, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Crossed Genres, Inscription, Uncanny, all of those have either explicitly called for diverse fiction in their guidelines or have gained a reputation for publishing and promoting the same. All of them depend on community support to exist. That interpersonal dependence has made some fantastic things possible. Uncanny happened because of a Kickstarter campaign. Strange Horizons just finished up their annual fund drive. Crossed Genres’s fantastic anthology Long Hidden: Speculative Fiction from the Margins of History was also a successful Kickstarter project, as was The Future Fire‘s We See a Different Frontier, which is an anthology of postcolonial speculative fiction. Women Destroy Science Fiction! was a Kickstarter project, as were Women Destroy Fantasy! and Women Destroy Horror! (Queers Destroy Science Fiction! will follow next year). Clarkesworld just successfully launched its Kickstarted project to bring more translated stories into its issues in an effort to give exposure to SFF writers working outside of the English-speaking West. The Book Smugglers, hitherto a review site, has opened its doors to fiction submissions and is seeking to make things as diverse as possible.

We’ve all worked very, very hard for this. And there’s been resistance. It’s been a fight, and sometimes the fight has been ugly. But things are opening up. The field is richer. Amazing stories are being told that, prior to digital short fiction markets, probably would never have found an audience. This is why we do what we do.

Terraform came on the scene with a first issue full of white writers, no indication of community engagement or statement regarding diversity, suggested none of that work matters, and announced that they were here to fix a problem that doesn’t exist.

What people need to understand is that for many of us, this isn’t about our precious feelings being hurt or having a new kid come to play in our sandbox uninvited. This is about erasure, and processes of erasure that go way back and cut very deep. I’m not saying Terraform intended to do that. But that’s what they did.

They’ve since altered their opening statement – though not the first paragraph – and have said that because of how they’re positioned they hope to bring short SFnal fiction to readers who otherwise wouldn’t see it. That’s great. We need that so much. But that’s not what they said.

Do I seem emotional? I am. Not gonna pretend not to be. This matters to me, to us, for reasons that go far beyond injured pride, and that’s why we reacted the way we did. No, Terraform was and is under no obligation to adhere to community norms. But there are social consequences for not doing so, and we saw that.

I’m glad Terraform is here (TWENTY. CENTS. A. WORD.). I mean that. I’m really looking forward to seeing where it goes. I hope I see some friendly names appearing there (I already have, and that makes me happy). I hope to maybe even show up there myself someday. But there are things they need to do. They’ve already done some of them.

I’ll be watching to see what they do next.

Oh, and if you like short SFF fiction? If you maybe even think you might but have yet to try it? Any of those links up there. Any of them at all. You won’t be sorry. Strange, terrible, and beautiful worlds await.

Sarah is science fictional on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry