Earlier this week I wrote about what’s become known as GamerGate (can we please call a moratorium on affixing ‘gate’ to things? Just a personal request) wherein I compared the science fiction and fantasy community – in which I’m a writer – to the gamer community – in which I’m a consumer. I drew parallels between the two, mostly concerning the creation of an identity that begins in defiance of perceived “mainstream” culture and then becomes an identity perfectly situation to be marketed and sold to.

But there’s an important difference between the SF&F community and the gamer community that’s worth noting, because of the difficulties it reveals concerning positive change in the later: the ability of community members to participate directly in the creation and recreation of the community’s culture.

In the previous post I linked to Matthew S. Burns’s discussion of gamers as “consumer-kings”, whose gamer identity is centered around the consumption – often conspicuous – of games. In other words, what we’re essentially dealing with, at least where the mainstream is concerned, is consumer capitalism masquerading as an actively agentic identity (“by gamers for gamers”, “power to the players”). This isn’t to say that there’s no agency at work, nor that there’s no culture mutually created by “community members”, merely that the culturally situated identity of “gamer” has been almost entirely co-opted by the game industry as a marketing tool. The identity itself is sold as part of the products: consume this and be that.

Which plays a tremendous role in the persistence of the toxic elements of gamer culture: when you’ve been told you’re special and important because of the identity you’re being sold, you’ll perceive a change in anything that props up that structure as profoundly threatening.

But there’s more, and this is where we have to talk about science fiction and fantasy.

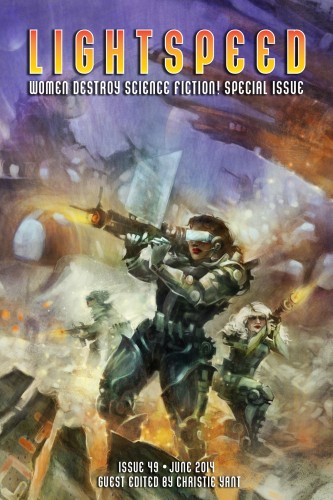

I’ve been writing and publishing SF&F for about five years now. In those five years I’ve witnessed powerful pushes forward on the part of people seeking to make the genre welcoming and inclusive for women, people of color, trans* people, and other marginalized identities. I’ve seen big Nebula wins, big Hugo wins, The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms and Ancillary Justice and Women Destroying Science Fiction and Long Hidden, several WisCons, battles fought and won over the right of people to not be harassed or assaulted at conventions, and countless other victories that I’m remiss in listing. But I’ve also seen endless ugly pushback, harassment and threats, open declarations that These People Don’t Belong Here, and an almost constant background radiation of grossness. Much of which looks a great deal like what we’ve seen in gaming.

The difference is that I’ve been writing in that community. I wanted to create, and I did. I started writing, I started publishing, and more specifically, I started writing what I was writing because it was what I wanted to read, it was what I thought there wasn’t enough of. I know so many people who started writing for that reason. It hasn’t been without difficulty, and marginalized people run into massive pushback and resistance way too frequently, but it can be done, and successful books like I listed above do happen.

More importantly, it can be done with much more practical ease than what has been suggested I do: dropping everything and making a game. The point is that if I don’t like SF&F culture, it’s quite conceivable – though no means simple or easy – for me to actively contribute to the changing of that culture through my own creation.

I could sit down tomorrow and write a novel in three months or so, and very possibly sell it in a few months more. I am not going to sit down and make an AAA video game. No one person can do that: they take entire development teams years and millions of dollars, and require the backing of large publishers to market and distribute. In other words, the barriers to entry are rather high. Considerably higher still if you’re not a white cisgender man.

But I’m talking about the mainstream market. What about the indie scene? Because there is an indie game scene, some would say a flourishing one. Those games tend to be smaller enterprises, things that can feasibly be made by a small group of people, or even one person working alone.

The problem is that – as Mattie Brice has observed – the indie scene is potentially subject to the same market forces as the AAA part of the industry. Further, that once you move out into where a lot of the really weird and interesting stuff happens, where identity is being questioned and examined, engagement is being rethought, and the very idea of play is being played with – Twine games, other text-based games, minimalist games – you’re talking about the margins of the community, at least as far as what people generally think of when they think “gamer”.

The people who are doing the potentially genuinely culture-altering stuff are not the consumer-kings, nor are they the people presenting the kings with their sumptuous feasts and thereby their identities as kings.

The consumer-kings consume. They don’t create. They don’t change. They have power, but what kind of power? From where? To do what?

This isn’t to say there’s no creative or transformative work, or that there’s no overlap anywhere, or that this all isn’t somewhat oversimplified. It’s simply to point out that in these two communities there exist processes of cultural production and reproduction in which power works very differently, and participation has a very different potential and actual meaning. Which means that the profiles for what’s possible and reasonable regarding cultural change – and the timeframe under which it’s likely to occur – look quite different as well.

Despite the ugliness I’ve seen, I’m very optimistic about the SF&F community. I think amazing things lie ahead.

I wish I could say the same for video games.

Sarah is on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry