When news stories started popping up around the mysterious YouTube account Webdriver Torso, more than one person noted that the truth behind it would almost certainly turn out to be nowhere near as interesting as all the speculation about what that truth might be. More than one person suggested that it might be better if no one find out the truth at all, because mysteries are pleasurable, no matter how much we might think we want them to be solved.

A quick primer, for those who don’t know (this has been going on for a while but only came to my attention in the last few weeks): Webdriver Torso features approximately 77,000 separate 10 second videos featuring cycling colors and tones. The purpose of these videos and their content was unknown, and of course, this being the web, there was a frantic search for explanations as well as frantic speculation about same.

The explanation – of course – turned out to be very mundane:

Isaul Vargas, a New York-based software tester, spotted the videos in a post on BoingBoing and recognised them from an automation conference he had been at a year ago. They were being shown by a European firm that made streaming software for set-top boxes, the kit that sits under a TV and connects to services such as Sky or Netflix.

The company needed to be able to quickly and reliably upload digital video, a capability which it tested by uploading short, randomly generated snippets to its YouTube channel and running image-recognition software on it. “Considering the volume of videos and the fact they use YouTube, it tells me that this is a large company testing their video encoding software and measuring how Youtube compresses the videos,” says Vargas.

Cue disappointed sigh. But the explanation doesn’t interest me so much as how people reacted to this account and what they saw in it.

Something that pops up again and again in these news stories is Horse_ebooks, primarily – I think – because that’s the easiest social media reference point for many people. What was great – and frustrating – about Horse_ebooks was what it revealed about our fascination with perceived signals in the noise, with hidden meaning behind what seems random. It served as a reminder that we are, as I said in a post after the Horse-ebooks outing, “little sacs of walking pattern recognition algorithms”.

With Horse_ebooks, though, we thought we had the answers. We thought we knew what was going on. We didn’t. It wasn’t just a bot, it had real intent and purpose, and it was not randomness, at least not completely. And that ended up being disappointing for a lot of followers, because the meaning we thought we had found for ourselves had been put there by actual people. Our story was not legitimate. It wasn’t just that the explanation was mundane; we thought we already had the explanation, and it was mundane. The problem was that a lot of people felt lied to.

Webdriver Torso was and is something quite different, and I think we can analyze it using the concept of the uncanny. With some modifications.

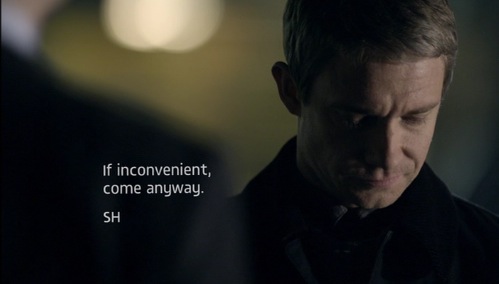

The uncanny, as it’s commonly used, refers to the “uncomfortably strange”, things that are almost recognizable but which fall short in such a way as to make us feel disoriented and repulsed – as with robots who look just human enough to be majorly creepy. That latter definition isn’t entirely useful when it comes to Webdriver Torso, because it doesn’t make much room for attraction and fascination, which we tend to feel even for the most nightmare-fueling mysteries. Webdriver Torso is uncanny because it presents the possibility of a signal that we feel we almost understand, but that lack of understanding is discomfiting and even frightening, depending on the context. We recognize order. Chaos is bewildering and therefore scary. But the hints of order lurking within chaos are uncomfortable on an entirely different level, because we can’t understand and we desperately want to in a very instinctive way.

An additional useful and related concept is abjection – an object that has been removed from the familiar symbolic order and is therefore rendered strange and threatening. The difference here is that this kind of mystery hasn’t been removed from anything. It comes from the outside unknown and is unknowable; we feel like it should fit somewhere but it doesn’t. It doesn’t upset the social order but rather the order by which we understand anything at all. Normal ways of understanding no longer apply.

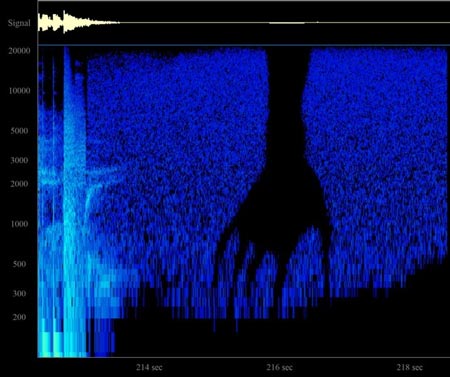

Another example that shows up in a number of these news pieces – an example that I think is much more analogous – is that of numbers stations. The explanation for the weird sounds and voices carried by these shortwave signals seems to also be relatively mundane, though still pleasantly unsettling: they’re probably coded signals being sent to various undercover agents in various countries, shortwave radio being quite appropriate to the task. But the codes themselves are just that kind of uncanny: hints of signal in the noise that tantalize and unsettle. One of the best examples of this is the deeply creepy “Swedish Rhapsody”:

Mysterious children’s voices are never not creepy, by the way.

What makes this particular to contemporary forms of technologically-mediated communication is that we’re especially primed to look for signals in that noise and therefore especially worried when we aren’t quite able to grasp those signals. This obviously isn’t confined to the web; radio seems to do the job just as well. There’s also, I would argue, something specific about audio that lends itself to this kind of uncannyness. Couple audio with video/images, as in the case of Webdriver Torso, and you truly have something special.

We can also see fascination with this kind of uncanny mystery in certain Augmented Reality Games (ARGs). Much of the time we know what we’re dealing with, but sometimes we only find out once we’re pretty deep into it, and in any case the results can feature exactly that kind of spine-shiver that one gets from listening to numbers stations recordings late at night. I’ll never forget how I felt when I saw the spectrogram image that someone pulled out out of the static at the end of one of the songs on the Nine Inch Nails album Year Zero.

So what differentiates the workings of our capacity for pattern recognition between things like Horse_ebooks and Webdriver Torso is that mystery, that need to understand, and discomfort at the elusiveness of the signal. Of course the understanding is never as fun. But the discomfort, while it lasts, is something we treasure even as it keeps us up at night.

Sarah is frequently unknowable on Twitter – @dynamicsymmetry