Facebook and Twitter, like any other form of communication, can be used to forge solidarity. As philosopher Richard Rorty reminds us in Method, Social Science, and Social Hope, one of the boundless powers of the humanities and of storytelling—novels, journalism, ethnographies, photography, documentaries—is to grow our imaginations so that the norms which would exclude foreigners, or the poor, or minorities, are replaced with a solidarity against suffering. In stories like Native Son, The Diary of Anne Frank and Brokeback Mountain, the cruelties of those who are not familiar to us are described in astonishing, bright detail. The humans who populate Dirty Pretty Things, Sin Nombre and How to Survive A Plague become less distant, more familiar. Through imagination, their suffering becomes ours. In many instances, networked media facilitate this kind of sensitivity building, this form of democratic attunement. But under the ceaseless pressure of shareability and virality, tragedy on social media often resembles disaster porn: a ghastly vine, a sappy post, attention seeking hashtags, confusing the spread of symbolic images for enduring political achievement.

Facebook and Twitter, like any other form of communication, can be used to forge solidarity. As philosopher Richard Rorty reminds us in Method, Social Science, and Social Hope, one of the boundless powers of the humanities and of storytelling—novels, journalism, ethnographies, photography, documentaries—is to grow our imaginations so that the norms which would exclude foreigners, or the poor, or minorities, are replaced with a solidarity against suffering. In stories like Native Son, The Diary of Anne Frank and Brokeback Mountain, the cruelties of those who are not familiar to us are described in astonishing, bright detail. The humans who populate Dirty Pretty Things, Sin Nombre and How to Survive A Plague become less distant, more familiar. Through imagination, their suffering becomes ours. In many instances, networked media facilitate this kind of sensitivity building, this form of democratic attunement. But under the ceaseless pressure of shareability and virality, tragedy on social media often resembles disaster porn: a ghastly vine, a sappy post, attention seeking hashtags, confusing the spread of symbolic images for enduring political achievement.

That grief is best endured in groups was not lost on those involved in the Boston Marathon or to those who experienced it through networked media. As platforms for articulating emotion, the streams of Twitter and Facebook have been inflected with profound sympathy, unabashed condolence, and a peculiar kind of catastrophe catharsis. Blood drenched pavement has a way of putting petty difference in its place. Tragedy breeds camaraderie.

Mark Zuckerberg’s Law—that each year we will share more of our life-moments on social networks—and Facebook’s axiom, that everything is better when shared with friends, fits nicely into this paradigm. The “My heart goes out to the victims in Boston” and “Prayers to law enforcement” posts can be seen as healthy extensions of sympathy. The hallmarks of Facebook’s logic—extraversion and sharing—seem acutely appropriate for coping with the psychic trauma of disaster.

But even the most gentle heart sees something amiss.

“Like” my kindhearted post where I word-vomit my benevolence onto a trending news story. Render unto me retweets for this unselfish link of teary, bleeding New England faces. Comment on my compassion even as I contort my very remote connection to Boston’s victims into a post that’s really about me.

In this cynical interpretation, documented sharing incentivizes Facebook and Twitter users to traffic in disaster porn. This is the depiction of destruction or tragedy in ways that do not enlighten, but merely sensationalize, pervert, exploit. The ego-stroking affirmations of social networks—the likes and RTs—the ones that push us to share new music and comment on engagement photos, seem perverse when dealing with gory misfortune. From this unsavory perspective, many of the declarations whizzing around Boston look like sympathy but smell like attention-seeking.

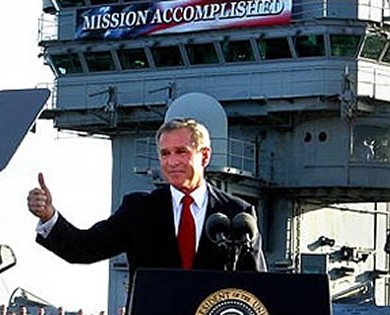

On television, disaster porn is more familiar to us. We’re used to the urge to aggrandize coverage of disastrous events. Attempts to place the episode in historical context or to remain attentive to the victims and their stories are merely secondary to the pornographic pursuit of the prurient. Give us the wrecked storefronts, the shattered car windows. Show us the mangled limbs, the protruding bones. Screaming, twisted faces? all the better! Viral shares are the old pageviews are the old ratings.

This is not an argument about the superiority of “real-life” communication over conversations on networked platforms. For a private message on Facebook or Twitter can be just as endearing as a hug or a handwritten note. Nor is this a claim that “true” empathy is never staged or performative. For attendance at a loved one’s funeral is, in part, a performance. Paying respect is to show that you care—an outward, public expression of solace. To remain skeptical of our use of social media in its current iteration isn’t to dismiss it as unworthy, but to examine our unquestioned habits exposed by jarring, surreal events, like what happened in Boston.

But to what extent are sympathy posts shrewd presentations more eager to convey emotional intelligence rather than sincere concern? If the shifting norm of social media is to always share more, then would not commenting on Boston indicate insensitivity or apathy? By incentivizing emotive broadcast around trending events, are less emotionally resonant but worthy subjects reflexively disregarded? These questions are not mean-spirited challenges to what many would call genuine emotion. They are inquisitive prods, pressing us to view the systems and incentives that can prize superficiality and crowd out other less loud, less popular, less homogenized human responses.

Consider the discussion led by philosopher Judith Butler in Frames of War. She reflects on why some lives are more grievable than others. Noted by more than a few journalists and intellectuals, the day that 2 pressure cookers exploded near the finish line of an international footrace—killing 3 and injuring 176—was the same day that a series of car bombs detonated across 6 provinces in Iraq, taking the lives of 42 and maiming 257. As enlightened democrats, we’d like to think that our brief and infrequent exposure to calamity would still make us more sensitive to the daily, lived-in plight of humans dwelling in a desert war zone. But we know this isn’t true. “Specific lives cannot be apprehended as injured or lost if they are not first apprehended as living,” Butler writes. The fragility of life plays a role in feeling sympathetic, but it doesn’t fully explain why it’s difficult for us to extend regard to others, especially those who do not look or speak like us.

Geographic and cultural closeness makes some events more tragic and painful. But closer to home, even before the FBI shootout that led to the citywide manhunt for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, an explosion at a West, Texas fertilizer plant took the lives of 14 Americans. Thus, the spectacle of domestic terror, played out on the news and in social media, makes us more attentive in ways that industrial calamity or foreign massacres currently do not.

What’s concerning about Facebook and Twitter use during disasters, then, is the social pressure to promote awareness along the same lines of sharability, RT-worthiness, and a familiar set of consumer-news demands.

In her Regarding The Pain Of Others, the thinker of photography Susan Sontag does not attempt to dictate which victims deserve our devotion. Nor does she indict us for not being psychologically transformed or compelled to political action after witnessing the gruesome. Rather, like Butler, she invites us to question our cultural reflex where “some people’s sufferings have a lot more interest to an audience than the sufferings of others.”

In the logic of social media sharing—especially on Facebook and to a lesser degree on Twitter—we are nudged relentlessly towards the viral. Zuckerberg’s law, when applied to disasters, becomes an overriding impulse: share and comment to inspire maximal stimulation with minimal, frictionless thought. And so, when those who were not high on CNN’s marathon miasma asked: what about the deaths in Iraq or the explosion in Texas? The reason for their perceived lack of coverage became clear: those events weren’t as sharable/viral/likable/worthy-of-(re)tweet.

This is an impoverished way of steering acknowledgement. By not examining the ethical implications of things like Facebook’s news feed algorithm, we accept, as simple market-truth, that what is shared most is most worthy of our thoughts. Researchers like Eli Pariser believe this creates a filter bubble of hyper-personalized selfishness, while others like Evgeny Morozov counter with concerns over “algorithmic paternalism,” the danger of forcing tech companies into roles as progressive civic guardians.

Still, thinkers on both sides of this debate illuminate the risks of ignoring how the news feed itself, with hidden and subtle bias, determines the reach and exposure of certain posts. (This same critique of social sharing can be applied to its forerunner and competitor, Google’s search engine optimization.) As with older forms of news media, this risks entering into a perverse agenda-setting of the moral. To accept an attention-grabbing rubric to determine cultural significance is to bolster the same kind of news norms that we recognize to be malevolent. These include a preoccupation with the global north, xenophobic privileging of moneyed American interests, highlighting pornographic disaster over chronic, pervasive crime, a disregard for victims who are not white, downplaying environmental degradation with no immediate, visible harm.

If we begin to scrutinize behavior generated and visible to us on social media, we can become more alert to our own reflexive cruelty and attentive to the misery of those who suffer at the bottom of news feeds and beyond “social graphs.”

In her penetrating analysis of the Twitter app Vine, Whitney Erin Boesel identities an irresponsible use of social technology. The particular vine that Boesel reviews captured the explosion of the first bomb. On an endless loop, the viewer witnesses “a sharable short story of this afternoon’s events that reduces the tragedy of a violent act down to a bright orange flash.” For Boesel, not only do vines of forever-repeating mayhem highlight carnage over context, they also encourage us to document disastrous events as yet another life-moment to be shared, like Facebook has done with nearly every facet of our social lives. “What would happen if putting tragedies on Vine became commonplace?” she asks. While Vine is not devoid of news value, Boesel urges us to consider its concealed potential to sterilize and repress shock. Conversely, she underscores the mental distress of consuming grisly, narrative-depleted disaster porn.

The hashtag “#prayers4boston” also made its way across the Twitter stream. While, theoretically, this hashtag could be used to inspire charitable collections for the victims’ families or as group therapy for tweeps, the hashtag also functioned in a bizarre and disingenuous way. It was, in Twitter’s linguistic shorthand, a crude mechanism to articulate sympathy. Outside of Twitter’s interface, it would be ridiculous to walk up to someone who just lost a spouse, shake hands, and utter the words, “hashtag sympathy.” This is precisely what took place within Twitter. Who was the intended audience for #prayers4boston? What of the craven wrongness of attaching the concepts of upvoting and trending to human loss?

The absurdity continued in photographs depicting Syrians and Iraqi children holding up signs of commiseration. “Boston bombings represent a sorrowful scene of what happens every day in Syria. Do accept our condolences” read one. Striking to the viewer that these far-away people are thinking about our domestic despair, the spread of these images by Americans became yet another crass, sympathy performance. These pictures could be interpreted to emphasize the peculiar suffering caused by the ongoing crises in Syria, which has commanded a remarkable lack of consideration. But this is too easy, too convenient. Like the #prayers4boston, to link out these photos is, at best, a kind gesture, but that’s all it is. Spreading these overly-figurative images is only to participate in a meme about sharing sentimentality—as weakly tied to transnational unity as stroking the pound sign on a keyboard.

After the uncle of the Tsarnaev brothers gave an impassioned, televised plea, writer Max Read used harsh sarcasm that perfectly captures how this news would travel through social media. “Hilarious Foreign Uncle Becomes Viral Star For Expressing Deep Emotion About Death Caused By Family Members VIDEO.” Instantly mutated into something packaged to be shared, the faux-headline has blatant disregard for those involved, and engages the reader as a sordid, entertainment-consuming drone. And, without much doubt, this hypothetical headline would rocket to the top of our feeds.

Hamza Shaban writes on Web culture and media studies. He’s on Twitter @PlanetHozz.