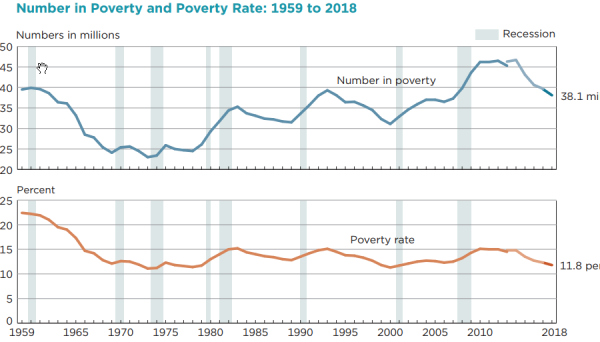

In the United States, poor people are judged harshly — especially when they receive government assistance or “welfare.” Yet, over 38 million people live in poverty. What people often forget, though, is that poverty itself is expensive. Social science research demonstrates that the poor pay more for necessities like housing and food, and debt can have serious consequences beyond just financial.

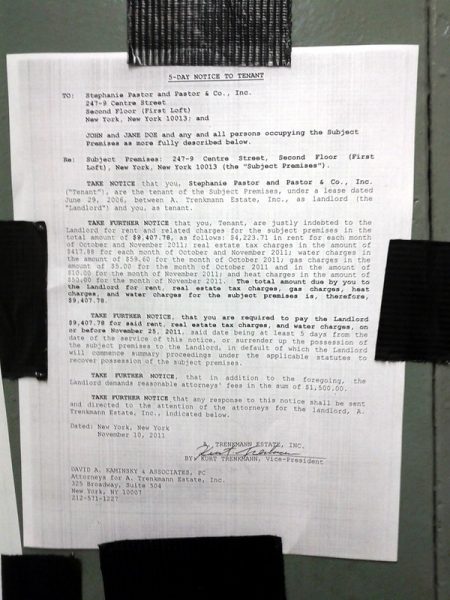

The poor pay significantly more for housing than others — sometimes 70% or 80% of their income. In 2018, low-income households paid over half their income for rent or lived in substandard housing. Further, landlords overcharge tenants in high poverty neighborhoods and those with higher concentrations of African Americans relative to the market value of the property. When families cannot afford basic needs they will make calculated tradeoffs to keep their housing, paying for rent instead of utilities to avoid eviction. Such tradeoffs often lead to compounded costs from late fees, and families living without water, electricity, or heat.

- Matthew Desmond. 2016. Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. Broadway Books.

- Matthew Desmond and Nathan Wilmers. “Do the Poor Pay More for Housing? Exploitation, Profit, and Risk in Rental Markets.” American Journal of Sociology

- Ryan Finnigan and Kelsey D. Meagher. 2018. “Past Due: Combinations of Utility and Housing Hardship in the United States,” Sociological Perspectives.

- Matthew Desmond and Bruce Western. 2018. “Poverty in America: New Directions and Debates.” Annual Review of Sociology 44: 305-18.

Poor families tend to pay more for food, too. Families with precarious housing situations especially struggle — If they do not have a stove or oven to cook with, or space to prepare meals, they must rely on food that can be prepared quickly, like microwave meals or fast food. And even when families are equipped to prepare meals at home, they often do not have the money upfront to buy in bulk, meaning they pay more for food in the long run. According to the USDA, a “thrifty meal plan”– choosing the cheapest options — costs a family between $567 and $651 per month, and this cost does not include home labor. One study estimates families of four would need to spend almost $400 on top of their food stamps to meet guidelines for a healthy diet.

- Sarah Bowen, Joslyn Brenton, and Sinnika Elliot. Pressure Cooker: Why Home Cooking Won’t Solve Our Problems and What We Can Do About It. Oxford University Press.

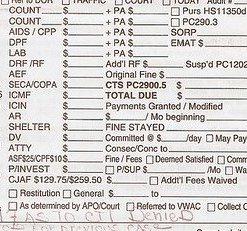

When poor people face fines and fees, their inability to pay or keep up with payments means they go further into debt. When these fees are part of the criminal justice system, failure to pay can also result in jail time. Anyone convicted of any type of crime is subject to fines and fees, from traffic tickets to felony convictions. And sometimes, these fees are not even dependent on a conviction: In North Carolina all felony defendants pay a “cost of justice” fee ($151.50) whether they are convicted or not. Until the costs are paid off, that person is tied to the criminal justice system — for the poor, this can be a lifetime.

- Alexes Harris. A Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions as Punishment for the Poor. Russell Sage.

- Karin D. Martin, Bryan L. Sykes, Sarah Shannon, Frank Edwards, and Alexes Harris. 2018. “Monetary Sanctions: Legal Financial Obligations in US Systems of Justice.” Annual Review of Criminology 1:471-95.

- Alexes Harris. 2014. “The Cruel Poverty of Monetary Sanctions.” The Society Pages, White Paper.

In the wake of the most recent proposed cuts to food stamps — a blip in a long U.S. history of cutting benefits for its poorest citizens — it is important to remember that poverty is not cheap.