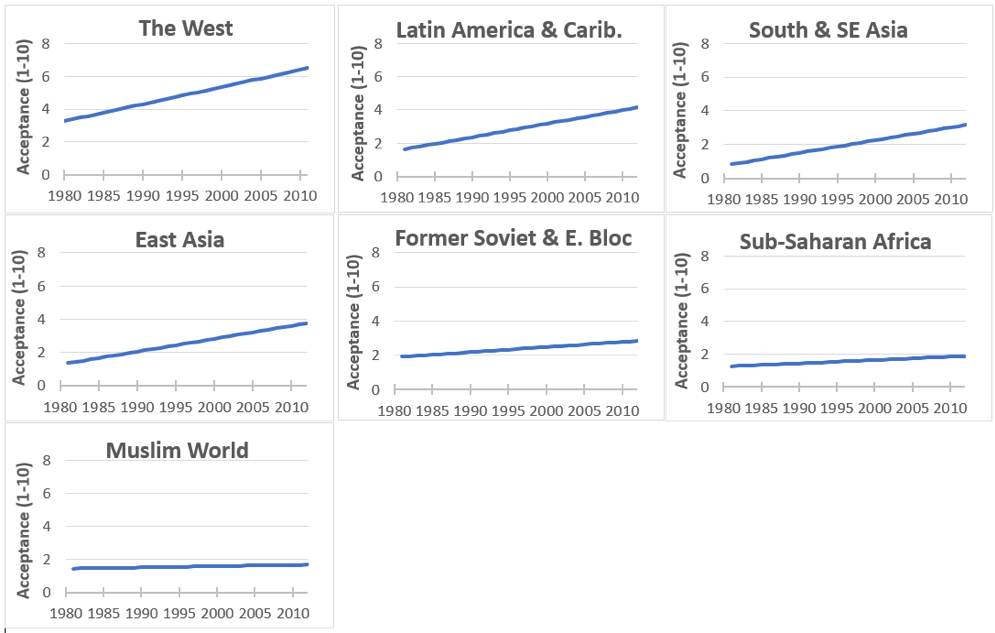

We know that public attitudes towards gay and lesbian people have become more favorable over recent decades in many Western countries, including in the United States. But we know much less about the attitudes of people around the globe. Have people’s attitudes outside of Western societies also shifted? In a new study, I find that the shift towards more favorable attitudes about gay and lesbian people has not been confined to Western countries. There has been a broad global upswing in the acceptance of same-sex sexuality. Between 1981 and 2012, attitudes became more favorable towards same-sex sexuality in most or all world regions, including Latin America and East and Southeast Asia. That said, average attitudes still vary greatly between countries. And some countries have changed much more slowly than others. Societies that had the least favorable attitudes in the early 1980s changed the most slowly, while societies that began with comparatively more favorable attitudes changed the fastest. As a result, the attitudinal gap between countries has actually widened over time.

In a recent Social Science Research article, I analyzed data on average national attitudes from 87 countries that together include 85% of the world’s population. The data were taken from the integrated World Values Survey/European Values Survey, which began in 1981.My study also addressed what factors explain the broad, global upswing in favorable attitudes towards gay and lesbian people — along with the slow pace of change in some countries and some parts of the world.

One type of explanation that has been forward to explain such trends is that economic development encourages more favorable attitudes toward same-sex sexuality. In other words, people in poor nations may be so focused on basic survival that they cannot afford to be as open as those in wealthy countries. However, my study failed to support this explanation. I find, for example, that countries that got wealthier over time actually became less favorable towards same-sex sexuality, net of other factors.

A New Global Norm

What does appear to explain the widespread upswing in positive attitudes towards same-sex sexuality is cultural globalization, and the associated worldwide spread of these favorable views. I find that acceptance of same-sex sexuality increased fastest in countries that were more exposed to the international flow of information and ideas – as measured by levels of international communication and travel, media consumption, and the import and export of books and other cultural products. More isolated societies with less exposure to the outside world changed more slowly.

I also find that more educated societies reported more favorable attitudes toward same-sex sexuality. This was likely because mass education systems tend to have a globalizing cultural influence. Research suggests that the norms that are accepted amongst an influential global elite — for example, norms surrounding human rights — are embedded in the educational curricula taught to students in schools and universities around the world.

Why should cultural globalization promote favorable attitudes toward same-sex sexuality? The answer has to do with the emergence of a new global norm on this issue. By “global norm,” I mean an internationally-influential norm that has for the most part been accepted within networks of international organizations like the United Nations and amongst elite, international communities of activists, professionals, and scientists.Over recent decades, acceptance of same-sex sexuality has increasingly become a global norm – although a controversial one. The emergence of the new norm can, for example, be seen in the creation of international lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) advocacy organizations and in the evolution of international law. The influential International Lesbian and Gay Association was founded in 1978, and the International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission was established in 1990. In international law, the European Court of Human Rights 1981 ruling in Dudgeon v. United Kingdom prohibited the criminalization of homosexuality in the European Union (EU). Thirteen years later, the international human rights system followed suit: in Toonen v. Australia (1994), the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Committee ruled that criminal prohibitions on homosexuality violated the UN International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Subsequent developments have further promoted the recognition of gay rights as human rights within international law.

The emergence of a new global norm can also be seen in the evolving stance of international scientific and professional communities and the global media. The American Psychiatric Association chose in 1973 to remove homosexuality from its official Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and the UN World Health Organization followed suit in 1990, when it dropped homosexuality from its International Classification of Diseases. Public health professionals have similarly shifted to promote the acceptance of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) individuals, especially through the international fight against HIV/AIDS. And the globalized media has often promoted the acceptance of homosexuality, via for example the influence of American movies and TV shows.

Arguably, the existence of a pro-acceptance global norm is revealed by international condemnations of deviations from it. For example, Russia’s passage of a law against so-called “homosexual propaganda” in 2013 met with a loud international outcry, especially surrounding the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia, which the leaders of the United States, France, Germany, Canada, and the EU pointedly refused to attend.

Backlash and Resistance

Given the emergence of the new global norm supporting same-sex sexuality, cultural globalization tended to spread a pro-acceptance message to people around the world.

Even so, same-sex sexuality remains far from universally accepted today. I find that membership in the Muslim World, sub-Saharan Africa, and the former Soviet and Eastern Bloc suppressed the rate of gay-favorable change over time (net of other factors). This may well be due to the influence of anti-gay rhetoric among political and religious leaders in these world regions. Certainly, political reaction and rejection of the “global” acceptance norm has occurred worldwide, including in Western countries like the United States. But that reaction and rejection have been particularly pronounced within the institutions and elite discourses of the Muslim World, sub-Saharan Africa, and the former Soviet and Eastern Bloc. Muslim governments and religious elites have forcefully rejected same-sex relations as a decadent Western import. And the leaders of many African nations have decried homosexuality as contrary to “African values.” At the international level, the Organization for Islamic Cooperation, the African Group, and the Arab Group have all actively opposed the recognition of sexuality rights. And approximately two-thirds of the 69 countries that still criminalized homosexuality in 2018 were sub-Saharan African or Muslim-majority nations.

Meanwhile, within the former Soviet and Eastern Bloc region, same-sex sexuality has frequently been opposed in the name of traditional values or a heterosexual, masculine national identity. For example, the Russian government led a campaign beginning in 2008 for the international recognition of universal “traditional values” – in opposition to “extreme feminist and homosexual attitudes.”

Increases in public acceptance of homosexuality have thus been slower in the Muslim World, sub-Saharan Africa, and the former Soviet and Eastern Bloc. In fact, my results suggest that the increased disparity over time between the global norm and the elite cultures of these three regions was in part responsible for the widening attitudinal gap between countries over the 1981-to-2012 period.

Religiosity also plays an important role. I find that, not only were more religious societies generally less accepting and slower to change, but they were also less receptive to the pro-gay ideas that were spreading around the world. In most countries, exposure to the international flow of ideas increased favorable attitudes toward gays and lesbians. But that was not true in highly religious societies. There, it appears that people tended to reject pro-gay ideas even when exposed to them. This makes sense given that people are not blank slates. They interpret new ideas, in part, on the basis of pre-existing cognitive frameworks. Religious frameworks may often have been seen as in conflict with the acceptance of homosexuality, leading to the rejection of pro-LGBTQ messages.Changing Attitudes in the Global Context

Despite the continued resistance to the acceptance of same-sex sexuality — which is substantial — my study suggests that people around the world live in an increasingly global community. Given the broad, worldwide rise in acceptance that has taken place over recent decades, it appears that most of us around the world are being influenced by the same ideas and cultural messages, at least to some extent.