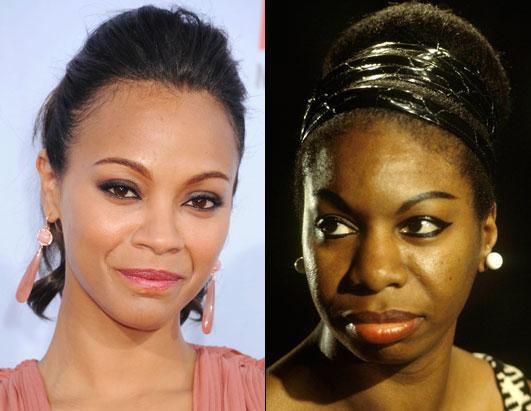

Zoe Saldana’s portrayal of singer and activist Nina Simone in an upcoming biopic has proven controversial, even before the film’s premiere. In press photos, Saldana, a light-skinned woman of color, is clearly wearing dark makeup and a prosthetic nose to appear more like the late singer. Some argue using “blackface” in order to cast Saldana is particularly troubling considering Nina Simone’s own life-long dedication to encouraging the acceptance and embrace of dark skin tones. It also ignores the realities of colorism, which reproduces social inequalities and hierarchies among people of color.

Several studies address the benefits that accrue to light-skinned women. Employers, for example, often evaluate women applicants on physical attractiveness, regardless of job skills. This includes privileging physical features that suggest lighter-skinned women are friendlier and more intelligent. Lighter skin tones also make their female bearers more likely to marry spouses with higher incomes, report less perceived job discrimination, and earn a higher income. In schools, studies find that teachers expect their lighter-skinned students to display better behavior and higher intelligence than their darker peers, and public health research shows lower rates of mental and physical health problems among lighter-skinned blacks.

- Margaret Hunter. 2007. “The Persistent Problem of Colorism: Skin Tone, Status, and Inequality.” Sociology Compass 1(1): 237-254.

- Ellis P. Monk, Jr. 2015. “The Cost of Color: Skin Color, Discrimination, and Health among African Americans.” American Journal of Sociology 121(2): 396-444

Colorism may provide socioeconomic, educational, and health benefits to light-skinned women, but it also challenges their identity as black women. Other blacks may perceive them as not “black enough,” assuming that they are more assimilated into white culture and lack awareness of black struggles. Those with lighter skin may feel isolated as members of their ethic group openly question their authenticity and belonging.

- Cedric Herring, Verna Keith, and Hayward Derrick Horton. 2004. Skin Deep: How Race and Complexion Matter in the “Color-Blind” Era. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.