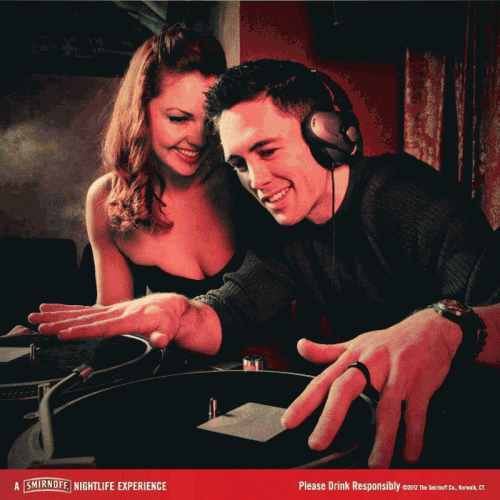

As a sociologist who happens to DJ — or is that the other way around? — I’m always curious to see how DJing is depicted in popular culture and advertising. Ever since the 1970s, when the disco craze helped push the prominence of DJs into the public realm, disc jockeys have become iconic symbols of nightlife culture. Within the milieu of the dance floor, DJs serve as what Sarah Thornton once described as “orchestrators of a ‘living’ communal experience.”

As such, the image of the DJ standing behind a pair of turntables has become ripe for appropriation by liquor and cigarette companies in particular. For them, especially in print ads, the DJ serves as a visual shorthand for any number of values they want their product associated with: culturally hip/cool, entertainment/musical mavens, the source of good times, etc. However, when it comes to that shorthand, this Smirnoff ad from last summer may have come up just a little too short.

At first glance, this image of a DJ working the turntables, with a cleavage-baring admirer looking on, seems uncomplicated: Smirnoff promises a fun, sexy time. However, a closer examination of the mise en scéne yields some instant problems.

- There are no records on the turntables.

- There’s not a mat on the turntables. Especially in a nightclub setting, DJs always use felt mats that sit between the platter and record. This not only protects the vinyl surface from the platter but by reducing friction between the record and platter, the DJ can “slip” a record into play at just the right moment. Hence, felt mats are called “slip mats.” In short, it’s very strange to see a turntable without a slip mat.

- There’s no needle on the turntable arm. Therefore, even if they had bothered to put records on the turntables, Mr. Hip DJ wouldn’t have been able to actually play them.

- There’s no visible DJ mixer. The mixer is absolutely crucial, allowing the DJ to switch between two audio sources, i.e. what makes “disc jockeying” possible to begin with. Normally, the mixer would sit between the two turntables so its absence in the image is conspicuous.

- The gesture — hands posed over both turntables — doesn’t make sense; it’s not a pose that any DJ would ever employ. Normally, you would have one hand on a turntable, the other hand working the mixer but no nightclub DJ would be manipulating both turntables, simultaneously. He looks like he’s trying to play bongos. (A scratch DJ, aka turntablist, may work both turntables for certain techniques but scratch DJs aren’t typically nightclub DJs – hard to dance to someone scratching).

When this ad made its rounds on social media, theories were bandied about to explain just what went wrong in this ad. The most plausible explanation is that the Smirnoff campaign selected a stock image hastily but that still opens up the question of how no one, from the original photographer, to the people in the image, to the people working on the Smirnoff ad itself, seemed to realize just how ridiculous this image was. It’d be akin to a car ad where someone is pretending to drive a car… from the backseat. With the wheels missing. And facing the wrong direction.

Of course, the vast majority of people know what driving a car is supposed to look like. One conclusion one might draw from the Smirnoff ad is that while the basic image of a DJ has some resonance in the public imagination, as a practice/craft, DJing isn’t actually well-understood at all.

————————

Dr. Oliver Wang is an associate professor of sociology at Cal State Long Beach. He contributes regularly on music and culture for NPR’s All Things Considered, KPCC’s Take Two, the LA Times, and KCET’s ArtBound. He also writes the audioblog Soul-Sides.com.