A polished version of this post was published in Contexts. You can download it here.

Most of our readers are probably familiar with the now-iconic “We Can Do It!” poster associated with Rosie the Riveter and the movement of women into the paid industrial workforce during World War II:

It is, by this point, so recognizable that it is often parodied or appropriated for a variety of uses (including selling household cleaners). The image is widely seen as a symbol of women’s empowerment and a sign of major gender transformations that occurred during the 1940s.

In their article, “Visual Rhetoric Representing Rosie the Riveter: Myth and Misconception in J. Howard Miller’s ‘We Can Do It!’ Poster,” James Kimble and Lester Olson argue that our current interpretations of the poster don’t necessarily align with how it was seen at the time.

While the poster is often described as a government recruiting item (Kimble and Olson give many examples in the article of inaccurate attributions from a variety of sources), it was, in fact, created by J. Howard Miller as part of a series of posters for the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company — the Westinghouse logo is clearly visible just under the woman’s arm, and the badge on her shirt collar is the badge employees wore on the plant floor, including an employee number. The War Production Co-ordinating Committee was an internal Westinghouse committee, similar to those created by many companies during the war, not a government entity.

The assumption of current viewers of the image is usually that it was meant to recruit women into the workforce, or to rally women in general — an early example of girl power marketing, if you will — and was widely displayed. But the audience was actually only Westinghouse employees. The company commissioned artists to create posters to be hung in Westinghouse plants for specific periods of time; this poster specifically says, “Post Feb. 15 to Feb. 28” [1943] in small font on the lower left. There’s no evidence that it was ever made available to the public more broadly. For that matter, the poster doesn’t identify her as “Rosie,” and it’s not clear that at the time she would have been immediately identifiable to viewers as “Rosie the Riveter”.

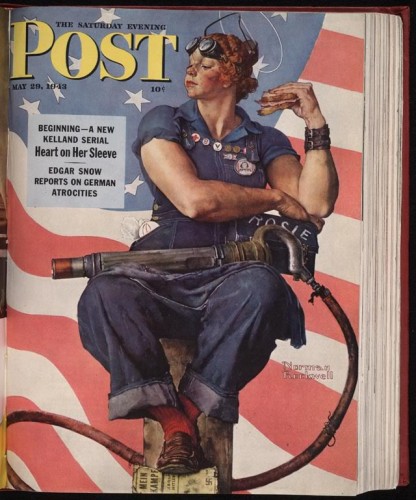

The image that was more widely seen, and is often conflated with the “We Can Do It!” poster, was Norman Rockwell’s May 29, 1943, cover for the Saturday Evening Post:

Here, the woman is clearly linked to the idea of Rosie the Riveter, through both the name on her lunchbox and the equipment she’s holding. She is more muscular than the woman in Miller’s poster, she’s dirty, and her foot is standing on a copy of Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Rockwell’s image presents the woman as a vital part of the war effort; her work helps defeat the Nazis. The image also includes fewer details to make her look conventionally attractive than Miller’s, where the woman has emphasized eyelashes and visibly painted fingernail.

Most interestingly, Kimble and Olson question the female empowerment message presumed to be the point of the “We Can Do It!” poster. We see the poster on its own, through the lens of a narrative about World War II in which housewives left the kitchen in droves to work in factories. But Westinghouse workers would have seen it in a different context, as one of a series of posters displayed in the plant, with similar imagery and text. When seen as just one in a series, rather than a unique image, Kimble and Olson argue that the collective “we” in “We can do it!” wouldn’t have been women, but Westinghouse employees, who were used to seeing such statements posted in employee-access-only areas of the plant.

Of course, having a woman represent a default factory employee is noteworthy. But our reading of the poster as a feminist emblem partially rests on the idea that this female worker is calling out encouragement to other women. The authors, however, point out a much less empowering interpretation if you think of the poster not in terms of feminism, but in terms of social class and labor relations:

…Westinghouse used “We Can Do It!” and Miller’s other posters to encourage women’s cooperation with the company’s relatively conservative concerns and values at a time when both labor organizing and communism were becoming active controversies for many workers… (p. 537)

…by addressing workers as “we,” the pronoun obfuscated sharp controversies within labor over communism, red-baiting, discrimination, and other heartfelt sources of divisiveness. (p. 550)

One of the major functions of corporate war committees was to manage labor and discourage any type of labor disputes that might disrupt production. From this perspective, images of happy workers expressing support for the war effort and/or workers’ abilities served as propaganda that encouraged workers to identify with one another and management as a team; “patriotism could be invoked to circumvent strikes and characterize workers’ unrest as un-American” (p. 562).

And, as Kimble and Olson illustrate, most of Miller’s posters included no women at all, and when they did, emphasized conventional femininity and the domestic sphere (such as a heavily made-up woman waving to her husband as he left for work).

Of course, today the “We Can Do It!” poster is seen as a feminist icon, adorning coffee cups, t-shirts, calendars, and refrigerator magnets (I have one). Kimble and Olson don’t explain when and how this shift occurred — when the image went from an obscure piece of corporate war-time propaganda, similar to many others, to a widely-recognized pop cultural image of female empowerment. But they make a convincing argument that our current perceptions of the image involve a significant amount of historical myth-making that helps to obscure the discrimination and opposition many women faced in the paid workforce even during the height of the war effort.

[The article appears in Rhetoric & Public Affairs 9(4): 533-570, 2006.]

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.