Flashback Friday.

In Race, Ethnicity, and Sexuality, Joane Nagel looks at how these characteristics are used to create new national identities and frame colonial expansion. In particular, White female sexuality, presented as modest and appropriate, was often contrasted with the sexuality of colonized women, who were often depicted as promiscuous or immodest.

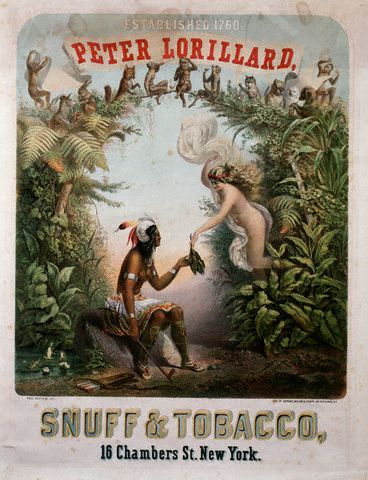

This 1860s advertisement for Peter Lorillard Snuff & Tobacco illustrates these differences. According to Toby and Will Musgrave, writing in An Empire of Plants, the ad drew on a purported Huron legend of a beautiful white spirit bringing them tobacco.

There are a few interesting things going on here. We have the association of femininity with a benign nature: the women are surrounded by various animals (monkeys, a fox and a rabbit, among others) who appear to pose no threat to the women or to one another. The background is lush and productive.

Racialized hierarchies are embedded in the personification of the “white spirit” as a White woman, descending from above to provide a precious gift to Native Americans, similar to imagery drawing on the idea of the “white man’s burden.”

And as often occurred (particularly as we entered the Victorian Era), there was a willingness to put non-White women’s bodies more obviously on display than the bodies of White women. The White woman above is actually less clothed than the American Indian woman, yet her arm and the white cloth are strategically placed to hide her breasts and crotch. On the other hand, the Native American woman’s breasts are fully displayed.

So, the ad provides a nice illustration of the personification of nations with women’s bodies, essentialized as close to nature, but arranged hierarchically according to race and perceived purity.

Originally posted in 2010.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.