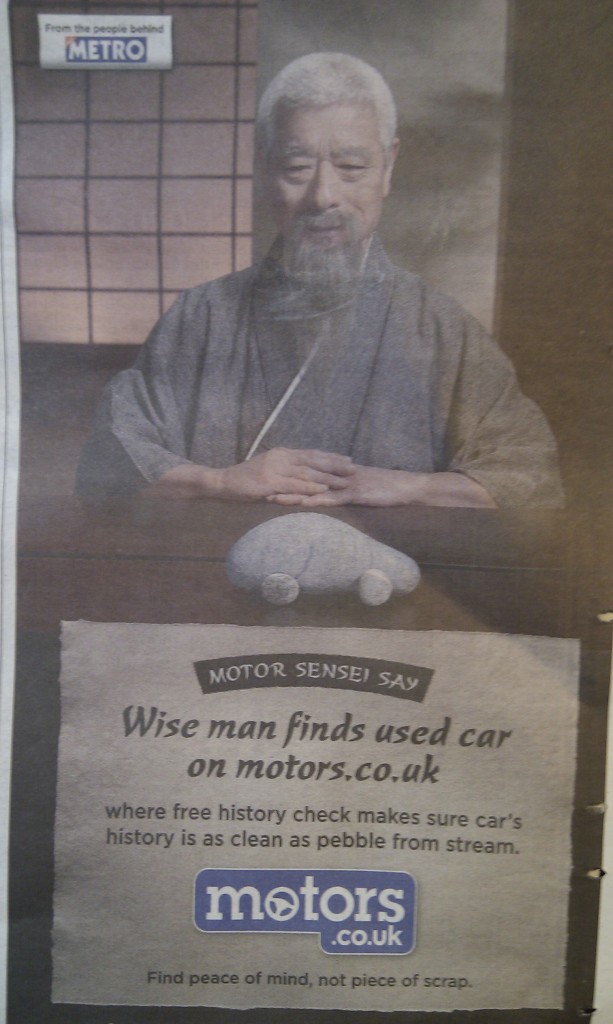

Sebastian sent in this ad for a used car website that uses the stereotype of the wise Japanese “sensei”:

We’ve got all the elements: the wise older man in a robe, stylized letters similar to what Margaret Cho describes as “feng shui Hong Kong fooey font,” the broken English, the reference to nature (“clean as pebble from stream”).

Related posts: Asian enlightenment used to sell food, and more food.