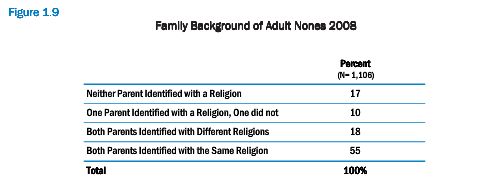

Data from the American Religious Identification Survey (collected in 2008) reveals some interesting things about the population of Americans that do not identify with organized religions: atheists, agnostics, and the “spiritual but not religious.” Most of the non-religious grew up with religious parents. Only 17% report that neither of their parents identified with a religion:

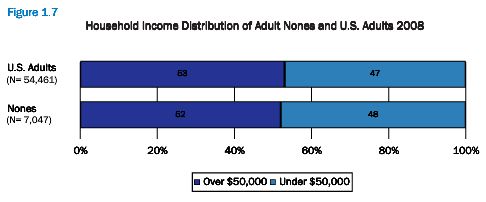

Being non-religious does not correlate with income or education:

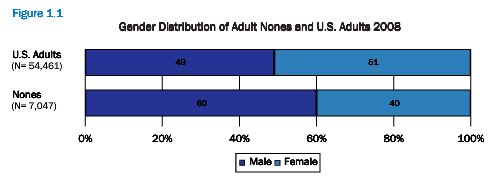

Instead, it’s strongest correlation is with gender. Women are more likely than men to believe in God, more likely to convert to a faith if raised as a non-believer, and less likely to leave a faith they are raised in.

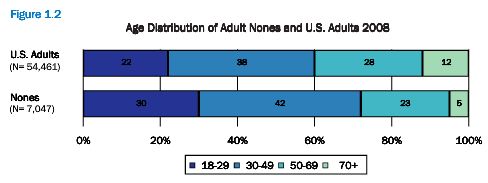

Younger people are also more likely to be non-religious:

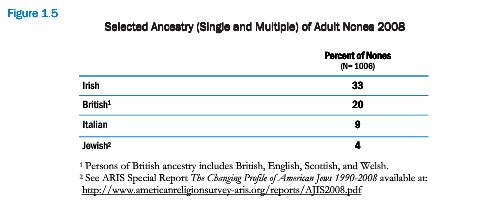

Americans with Irish ancestry make up a significant percentage of the non-religious. They account for about 12% of Americans, but about 1/3rd of all non-religious:

More details at American Nones.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.