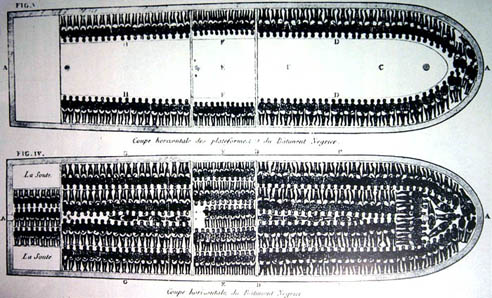

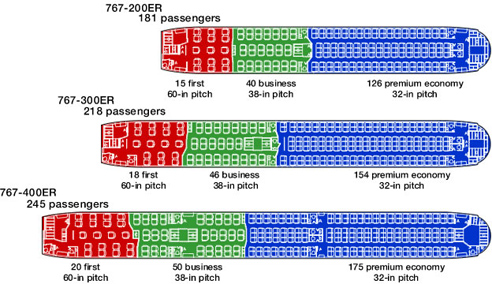

Just as “I’m not a racist, but…” is a sure sign that someone is about to say something racist, an essay that begins “I don’t want to trivialize the inhumane horrors that African slaves endured on slave ships destined for the Americas. But…” is certain to do just that. Indeed, Steven Heller at Imprint began his post this way, going on to suggest that the design of modern airplanes “resemble[s]” that of slave ships. As evidence, he recalls his own discomfort in coach and compares drawings of slave ships and blueprints of airplanes.

Heller prefaced his observations with a disclaimer because he knew comparing modern air travel to the slave trade was sketchy. And it is, indeed, sketchy. The descendants of slaves live life with the knowledge that their ancestors were stolen, shackled, beaten, and denied their very humanity; at least they survived the trip across the Atlantic. Nope, not like air travel one bit.

So, yes, it’s lovely to be clever, but it’s also lovely to be thoughtful and sensitive. In this case, Heller’s desire to be the former won out over the latter. Or perhaps he never really thought that anyone would seriously be upset by the comparison. It’s obviously tongue-in-cheek right? I mean, slavery has been over for, like, ever. Or maybe he forgot that descendants of slaves read the freakin’ internet just like everyone else.

Who knows. In any case, it’s a great example of the trivializing of the histories and traumas of a marginalized population.

Thanks to Dolores R. for the tip.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.