“First, let me say that I’m tired of all of this talk about ‘snubs,'” said an anonymous member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. And continued:

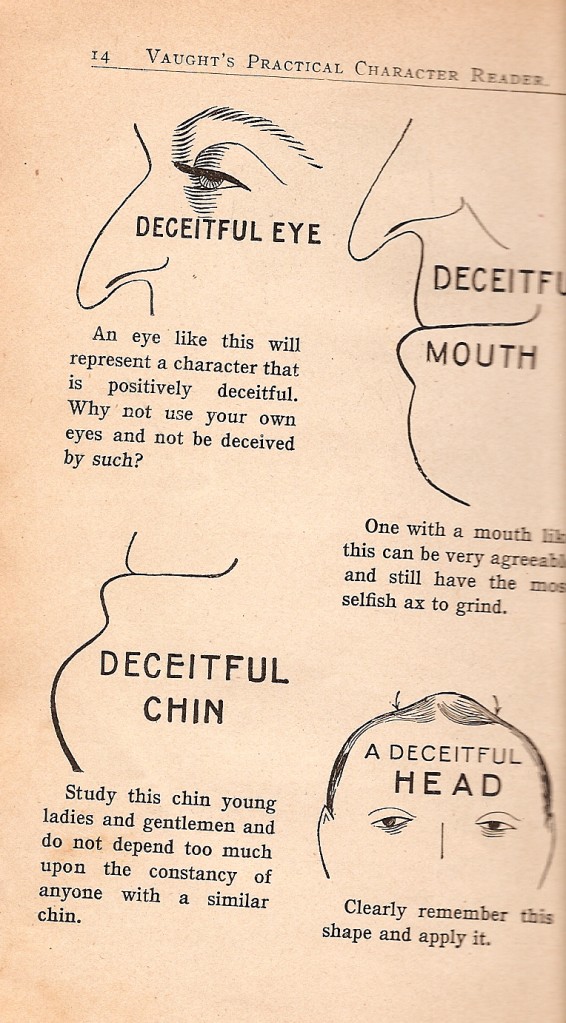

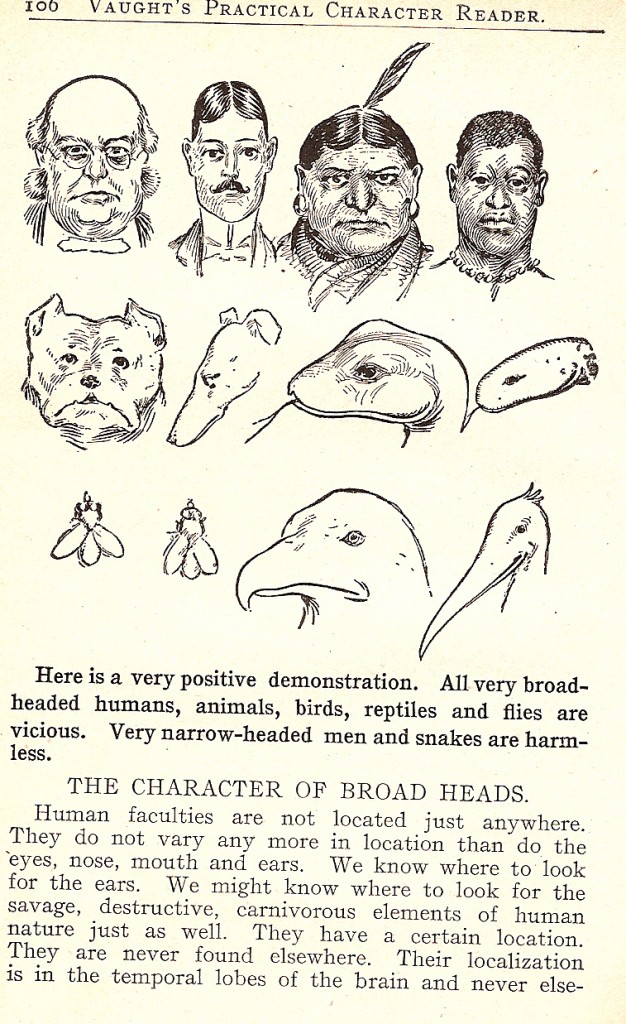

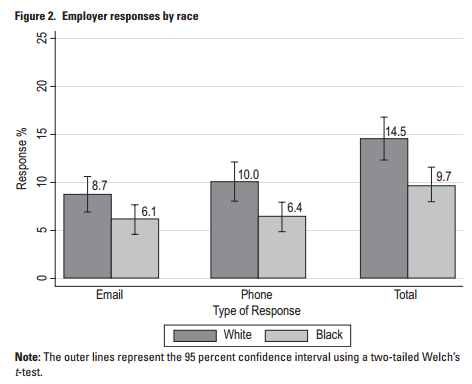

And as far as the accusations about the Academy being racist? Yes, most members are white males, but they are not the cast of Deliverance — they had to get into the Academy to begin with, so they’re not cretinous, snaggletoothed hillbillies.

In the video below, Jay Smooth takes on the idea that only “hillbillies” are racist and asks about the idea of the “good person” and what it actually takes to be one.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.