Lots of time and care consideration goes into the production of new superheroes and the revision of time-honored heroes. Subtle features of outfits aren’t changed by accident and don’t go unnoticed. Skin color also merits careful consideration to ensure that the racial depiction of characters is consistent with their back stories alongside other considerations. A colleague of mine recently shared an interesting analysis of racial depictions by a comic artist, Ronald Wimberly—“Lighten Up.”

“Lighten Up” is a cartoon essay that addresses some of the issues Wimberly struggled with in drawing for a major comic book publisher. NPR ran a story on the essay as well. In short, Wimberly was asked by his editor to “lighten” a characters’ skin tone — a character who is supposed to have a Mexican father and an African American mother. The essay is about Wimberly’s struggle with the request and his attempt to make sense of how the potentially innocuous-seeming request might be connected with racial inequality.

In one panel of the cartoon, you can see Wimberly’s original color swatch for the character alongside the swatch he was instructed to use for the character.

Digitally, colors are handled by what computer programmers refer to as hexadecimal IDs. Every color has a hexademical “color code.” It’s an alphanumeric string of 6 letters and/or numbers preceded by the pound symbol (#). For example, computers are able to understand the color white with the color code #FFFFFF and the color black with #000000. Hexadecimal IDs are based on binary digits—they’re basically a way of turning colors into code so that computers can understand them. Artists might tell you that there are an infinite number of possibilities for different colors. But on a computer, color combinations are not infinite: there are exactly 16,777,216 possible color combinations. Hexadecimal IDs are an interesting bit of data and I’m not familiar with many social scientists making use of them (but see).

There’s probably more than one way of using color codes as data. But one thought I had was that they could be an interesting way of identifying racialized depictions of comic book characters in a reproducible manner—borrowing from Wimberly’s idea in “Lighten Up.” Some questions might be:

- Are white characters depicted with the same hexadecimal variation as non-white characters?

- Or, are women depicted with more or less hexadecimal variation than men?

- Perhaps white characters are more likely to be depicted in more dramatic and dynamic lighting, causing their skin to be depicted with more variation than non-white characters.

If any of this is true, it might also make an interesting data-based argument to suggest that white characters are featured in more dynamic ways in comic books than are non-white characters. The same could be true of men compared with women.

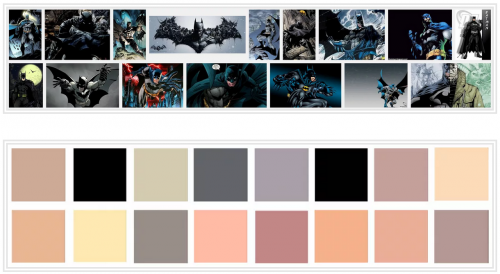

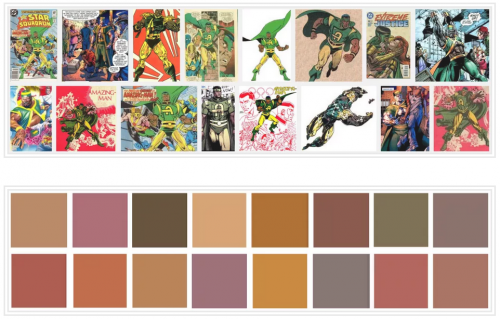

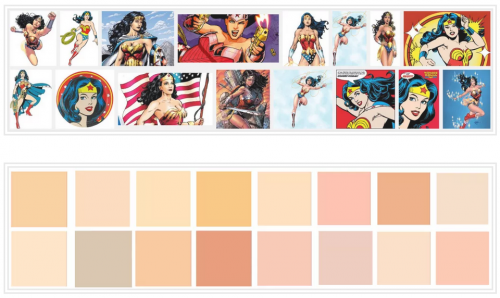

Just to give this a try, I downloaded a free eye-dropper plug-in that identifies hexadecimal IDs. I used the top 16 images in a Google Image search for Batman (white man), Amazing-man (black man), and Wonder Woman (white woman). Because many images alter skin tone with shadows and light, I tried to use the eye-dropper to select the pixel that appeared most representative of the skin tone of the face of each character depicted.

Here are the images for Batman with a clean swatch of the hexadecimal IDs for the skin tone associated with each image below:

Below are the images for Amazing-man with swatches of the skin tone color codes beneath:

Finally, here are the images for Wonder Woman with pure samples of the color codes associated with her skin tone for each image below:

Now, perhaps it was unfair to use Batman as a comparison as his character is more often depicted at night than is Wonder Woman—a fact which might mean he is more often depicted in dynamic lighting than she is. But it’s an interesting thought experiment. Based on this sample, two things that seem immediately apparent:

- Amazing-man is depicted much darker when his character is drawn angry.

- And Wonder Woman exhibits the least color variation of the three.

Whether this is representative is beyond the scope of the post. But, it’s an interesting question. While we know that there are dramatically fewer women in comic books than men, inequality is not only a matter of numbers. Portrayal matters a great deal as well, and color codes might be one way of considering getting at this issue in a new and systematic way.

While the hexadecimal ID of an individual pixel of an image is an objective measure of color, it’s also true that color is in the eye of the beholder and we perceive colors differently when they are situated alongside different colors. So, obviously, color alone tells us little about individual perception, and even less about the social and cultural meaning systems tied to different hexadecimal hues. Yet, as Wimberly writes,

In art, this is very important. Art is where associations are made. Art is where we form the narratives of our identity.

Beyond this, art is a powerful cultural arena in which we form narratives about the identities of others.

At any rate, it’s an interesting idea. And I hope someone smarter than me does something with it (or tells me that it’s already been done and I simply wasn’t aware).

Originally posted at Feminist Reflections and Inequality by Interior Design. Cross-posted at Pacific Standard. H/t to Andrea Herrera.

Tristan Bridges is a sociologist of gender and sexuality at the College at Brockport (SUNY). Dr. Bridges blogs about some of this research and more at Inequality by (Interior) Design. You can follow him on twitter @tristanbphd.