A survey of college and university presidents conducted earlier this year suggests that campus activists are making a difference. The American Council on Education asked 567 presidents about their experience with and response to activists on campus organized around racial diversity and justice.

Almost half (47%) of presidents at 4-year institutions said that such activism was occurring on their campuses and that the dialogue about such matters had increased (41%). The majority (86%) had met with student organizers more than once and more than half (55%) said that the “racial climate” on campus was more of a priority than it had been just a few years ago. The trends for 2-year institutions were weaker, but in the same direction.

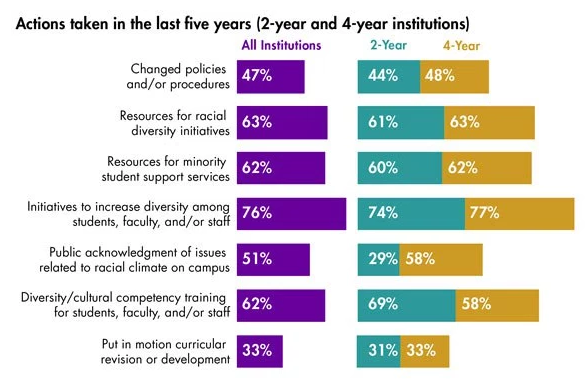

When asked what concrete steps they had taken to improve the racial climate, presidents reported a range of strategies:

As with all activism, progress requires vigilance, so it will be interesting to see how many of these efforts translate into real changes in climate. New policies and procedures can be toothless or even harmful, resources can be mis-spent and trainings can be terrible, public acknowledgement can be nothing but lip service, and curricular revision can die in committee. Still, these data point to the potential for activism to make a difference and are encouraging for those of us who care about this issue.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.