In the late 1800s, male Chinese immigrants were brought to the U.S. to work on the railroads and as agricultural labor on the West Coast; many also specialized in laundry services. Some came willingly, others were basically kidnapped and brought forcibly.

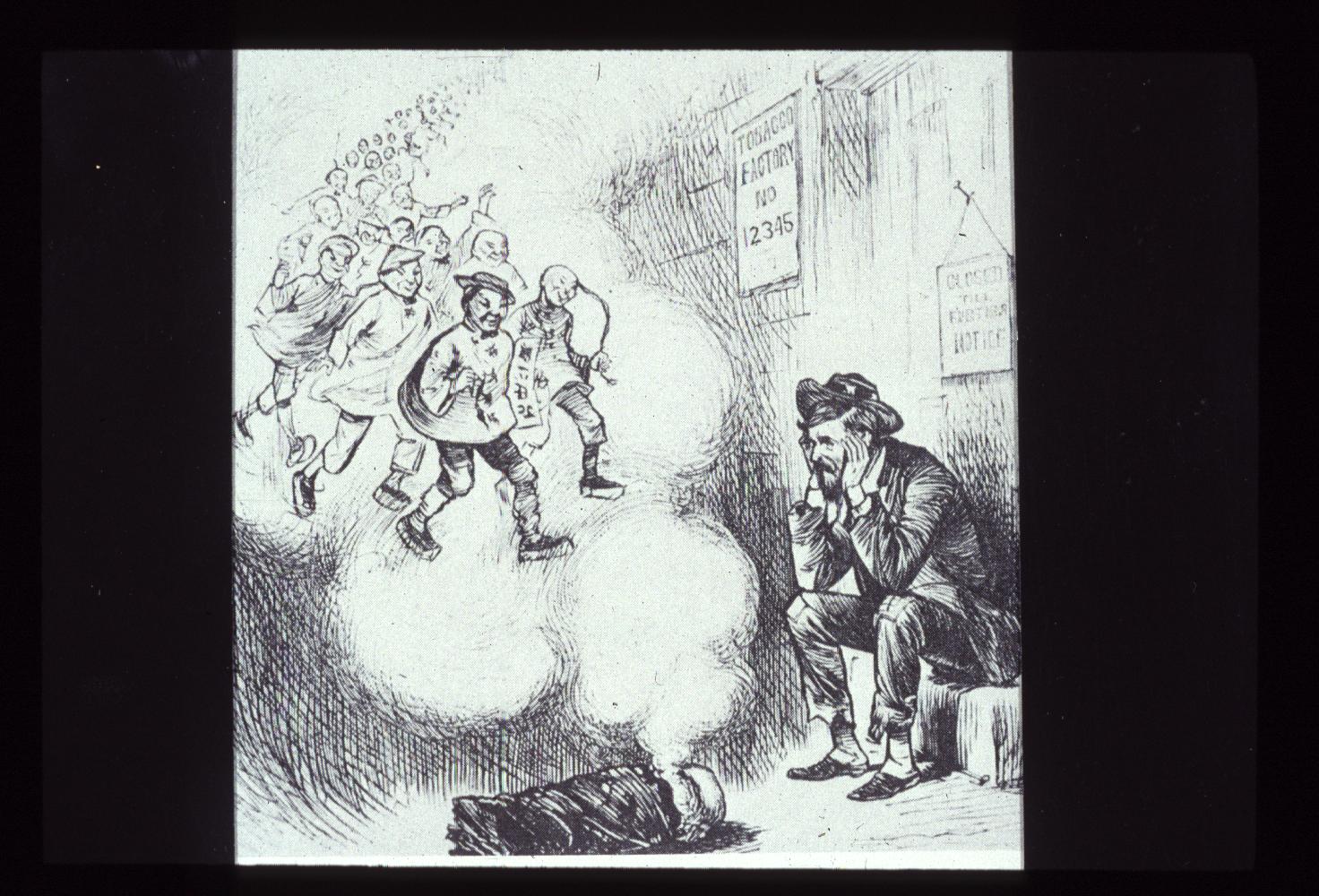

After the transcontinental railroad was completed, it occurred to white Americans that Chinese workers no longer had jobs. They worried that the Chinese might compete with them for work. In response, a wave of anti-Chinese (and, eventually, anti-Japanese) sentiment swept the U.S.

Chinese men were stereotyped as degenerate heroin addicts whose presence encouraged prostitution, gambling, and other immoral activities. A number of cities on the West Coast experienced riots in which Whites attacked Asians and destroyed Chinese sections of town. Riots in Seattle in 1886 resulted in practically the entire Chinese population being rounded up and forcibly sent to San Francisco. Similar situations in other towns encouraged Chinese workers scattered throughout the West to relocate, leading to the growth of Chinatowns in a few larger cities on the West Coast.

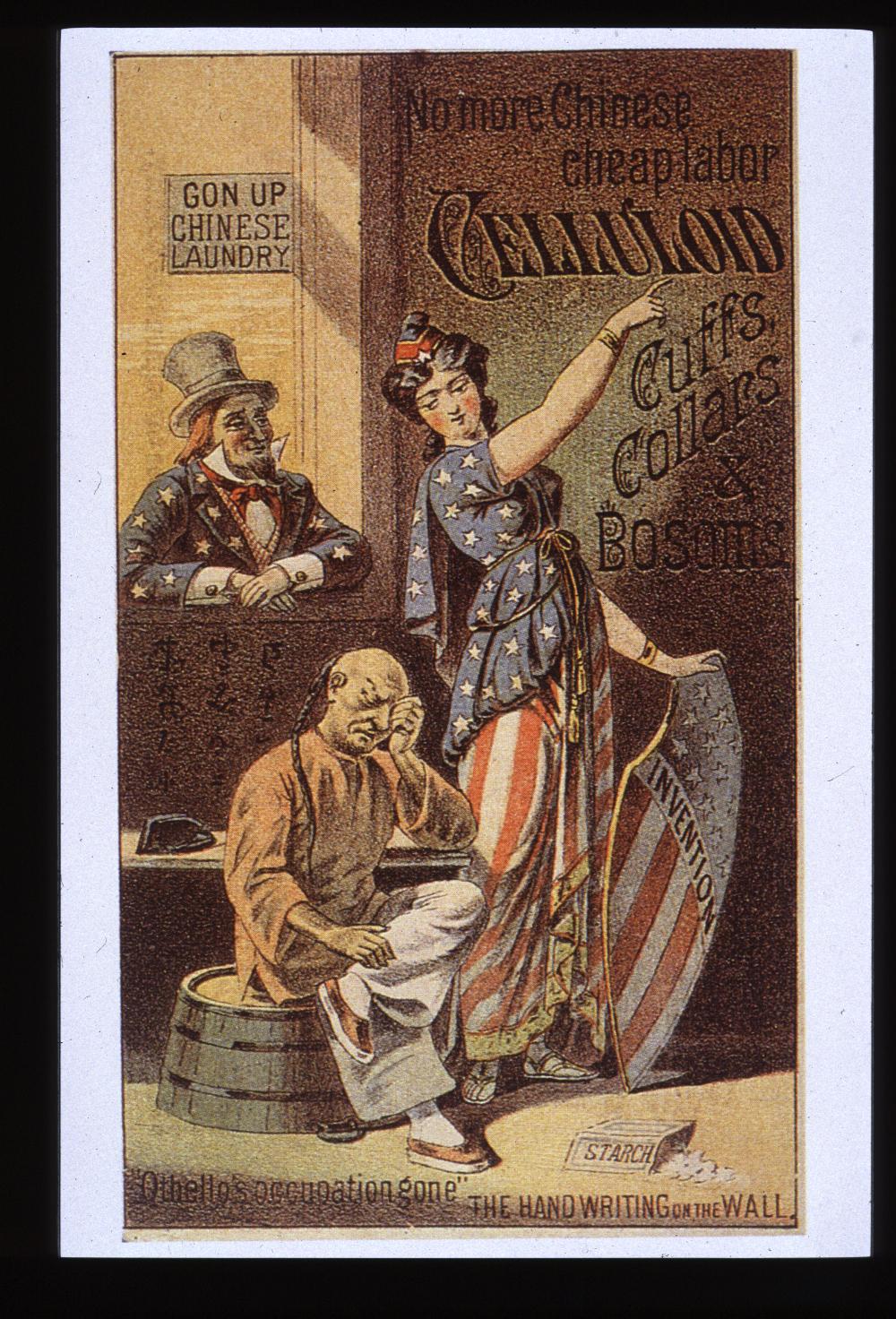

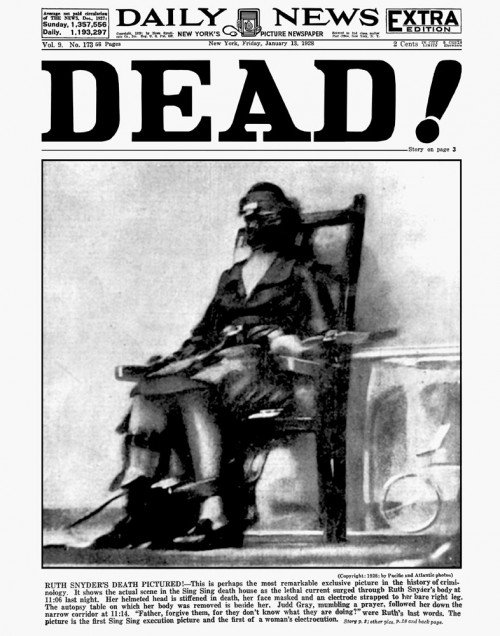

The anti-Asian movement led to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the Gentlemen’s Agreement (with Japan) of 1907, both of which severely limited immigration from Asia. Support was bolstered with propaganda.

Here is a vintage “Yellow Peril” poster. The white female victim at his feet references the fact that most Chinese in the U.S. were male–women were generally not allowed to immigrate–and this poster poses them as a threat to white women and white men’s entitlement to them:

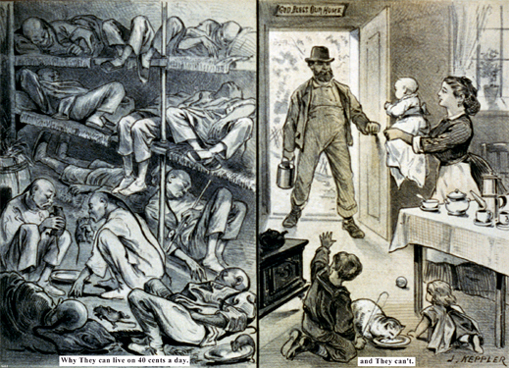

“Why they can live on 40 cents a day…and they can’t,” this poster says, referring to the fact that white men can’t possibly compete with Chinese workers because they need to support their moral families. The Chinese, of course, usually didn’t have families because there were almost no Chinese women in the U.S. and white women generally would not marry a Chinese man.

The following images were found at the The History Project at the University of California-Davis.

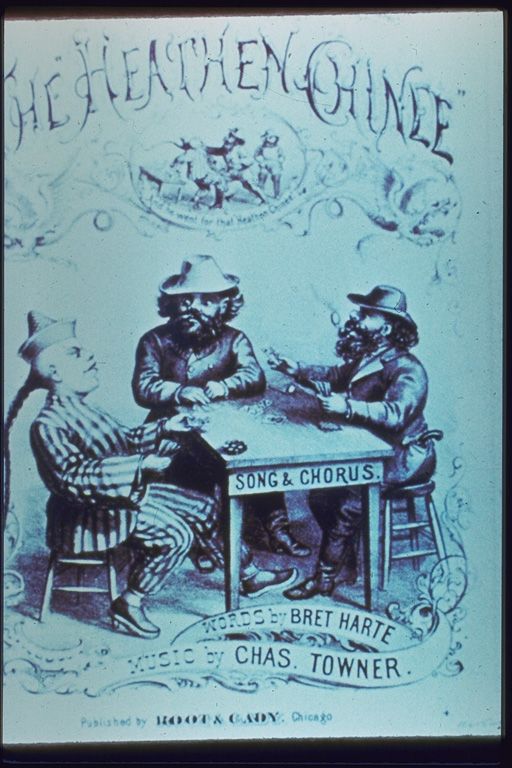

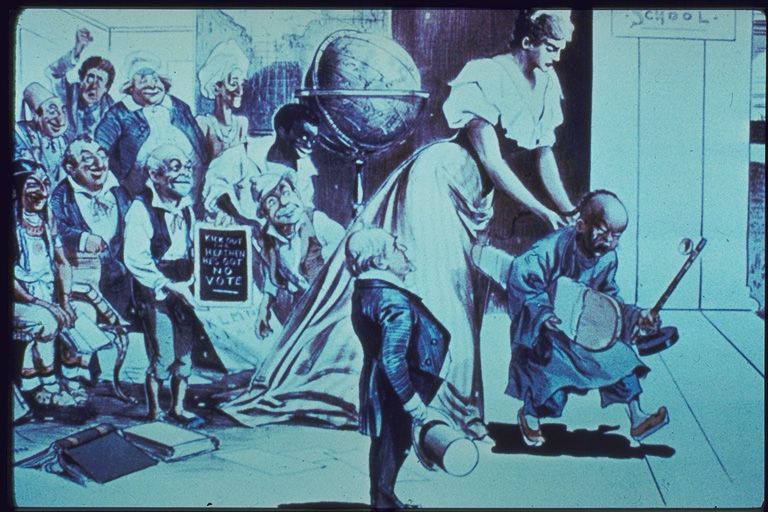

This is the cover for the song sheet “The Heathen Chinese”:

According to the History Project, this next image was accompanied by the following text:

A judge says to Miss Columbia, “You allowed that boy to come into your school, it would be inhuman to throw him out now — it will be sufficient in the future to keep his brothers out.” Note the ironing board and opium pipe carried by the Chinese. An Irish American holds up a slate with the slogan “Kick the Heathen Out; He’s Got No Vote.”

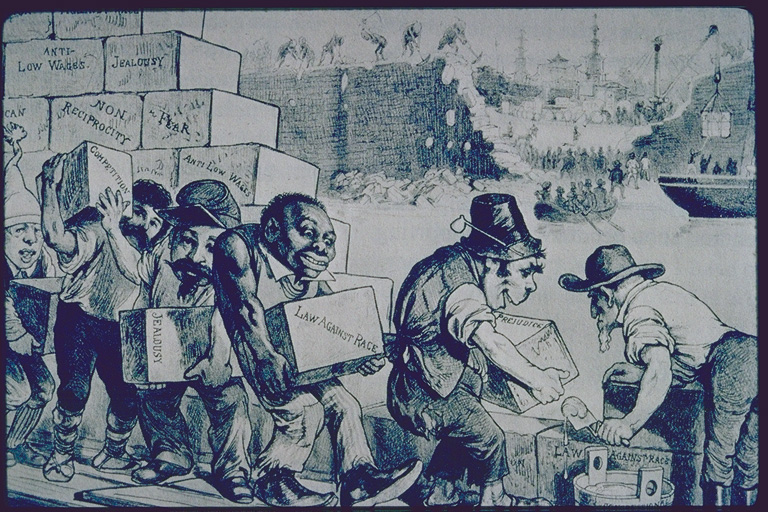

The following counter-propaganda pointed out how immigrants from other countries were now working to keep Chinese immigrants out. The bricks they’re carrying say things like “fear,” “competition,” “jealousy,” and “non-reciprocity.”

During World War II, attitudes toward the Chinese shifted as they became the “good” Asians as opposed to the “bad” Japanese. However, it wasn’t until the drastic change in immigration policy that occurred in 1965, with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act, that Asia (and particularly China) re-became a major sending region for immigrants to the U.S.

This post originally appeared in 2008.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.