In general, married couples are homogamous. That is, they are more likely than not to match on a whole host of characteristics: age, income, education level, race, religion, immigration history, attractiveness level, and more.

But, does homogamy really translate into compatibility? Or, do we just think it does?

OKCupid set about to find out. This is the second of two posts about recent revelations that they, like Facebook, have been doing experiments on users. The last one was a depressing look at the role of attractiveness on the site. This one is about the impact of match ratings. Yep, they lied to see what would happen.

OkCupid users answer a series of questions and the site then offers a “match rating” between any two users. The idea is that people with a higher match rating are more homogamous — by some measure not identical to those that sociologists typically use, to be clear — and, therefore, more likely to get along.

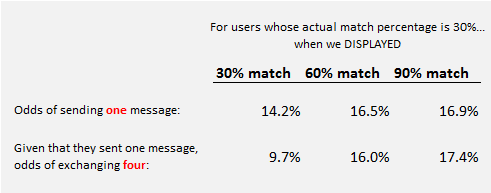

The first thing they did was artificially alter the match rating for couples whose true match was only 30%. Users could read the profile, look at the pictures, reviews answers to questions, and see a match rating. In other words, they had a lot of information and one summary statistic that might be true or false.

People were slightly more likely to send a message and continue a conversation if they thought they were a 60% match or better. This is interesting since all these couples were poorly matched and it shouldn’t have been too difficult to discover that this was so.

Rudder’s interpretation of the data is that you can make two people like each other by just telling them that they should.

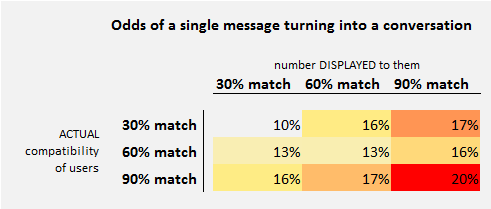

Or maybe, he considered, their algorithm was just terrible. So, they took couples who matched at the 30, 60, and 90% rating and displayed a random match rating that was wrong two-thirds of the time. Then, they waited to see how many couples got to exchanging four messages (their measure of a “conversation”).

The lower right corner suggests that the ideal situation is to be a good match and know it. Likewise, if you’re a bad match and you know it things probably won’t get very far. But the difference between actually being a good match and just thinking you are isn’t as big as we might think it would be. At least, not in the space of four messages.

So, does homogamy really translate into compatibility? Or, do we just think it does? Maybe a little of both.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.