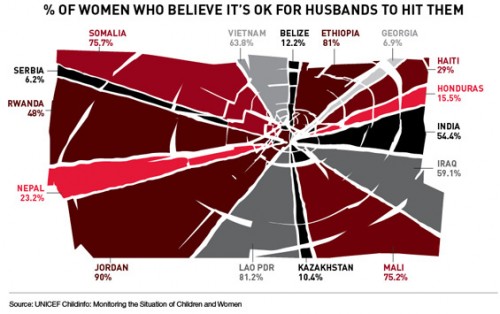

Teresa C. sent in this image created using UNICEF data to show what percent of women surveyed in various countries said it was acceptable for their husbands to hit them:

(Found at BuzzFeed.)

You can find the data and a breakdown of UNICEF data collection methods here. The data for many more countries are available there too. I can’t quite figure out why these particular countries were used in the image; they aren’t all of the countries with the highest percentages. As far as I can tell, the UNICEF data table only includes numbers for the “developing” nations and some countries from eastern Europe, which is UNICEF’s focus. But I do wonder what the numbers would be if you asked women in the U.S. a question along the lines of “is it ever acceptable for a man to hit a woman?” or “can you think of any situation where it might be understandable that a man would hit his wife or girlfriend?” You might get higher “support” for violence against women than you’d think. The UNICEF page doesn’t provide the wording of this question, which would be interesting to know.

That’s not to downplay the issue of women justifying or accepting violence against women, just that those of us in the “developed” nations need to be sure not to pat ourselves on the back too much about how enlightened we are about domestic violence.

And I can’t help but dislike the image, in that at first glance it would appear to be a pie chart in which all of the sections add up to 100%; really a bar graph would be a better way to illustrate this. But then, I had a dissertation advisor with a 5-page single-spaced document outlining his standards for data presentation.

UPDATE: Reader P. makes the point I was getting at above (that the wording might greatly impact how much “support” you find for violence against women) much better than I did:

What they were actually asked, in the MICS and the DHS (the two primary sources for the data), was this question:

“Sometimes a husband is annoyed or angered by things that his wife does. In your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations:

– If she goes out with out telling him?

– If she neglects the children?

– If she argues with him?

– If she refuses sex with him?

– If she burns the food?”

I bet you get very different rates for different “justifications,” which is important both for data-gathering/presentation and for anti-domestic violence campaigns. And, again, I bet if you broke down various “reasons” for hitting a woman, I bet you’d get higher-than-expected acceptance of them in countries in the “developed” countries that weren’t presented in the table.