It’s Valentine’s Day, and my social media feed is more snarky than smarmy. The Hallmark holiday gets us thinking about love, but it also highlights our unquestioned assumptions about romantic relationships. The culture of love is tied up in all kinds of expectations: what we buy, how we date, even who does the dishes. A lot of sociological thought works to make these assumptions explicit, breaking them down to reveal the (sometimes sad) truth that many of us haven’t really thought that much about how we really want to love and be loved.

But social science isn’t always depressing! Some recent work actually has pretty good news about the state of our romantic relationships. One example is Philip Cohen’s article published in Socius last year on “The Coming Divorce Decline.” Where many of us have gotten used to a story about rising divorce rates over the past few decades, Cohen finds that the probability of divorce for women has been declining from 2008 to 2017. Especially encouraging, he also finds that the probability of divorce for newly married women has been declining over same time period.

In the article, Cohen writes:

…because the risk profile for newly married couples has shifted toward more protective characteristics, it appears certain that—barring unforeseen changes—divorce rates will further decline in the coming years.

And he even highlights how new data supported this prediction from an earlier draft of the paper!

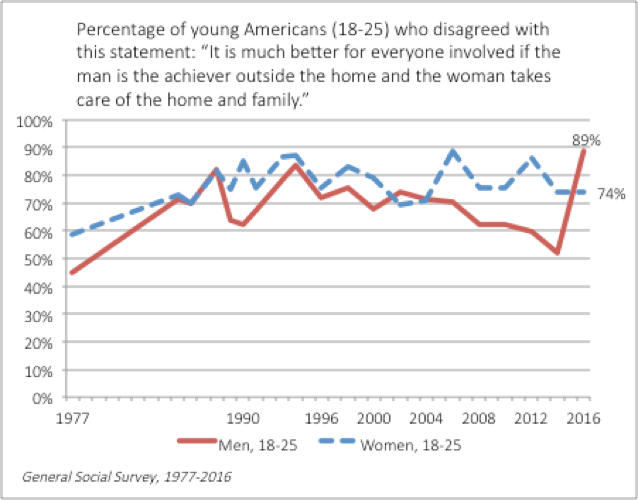

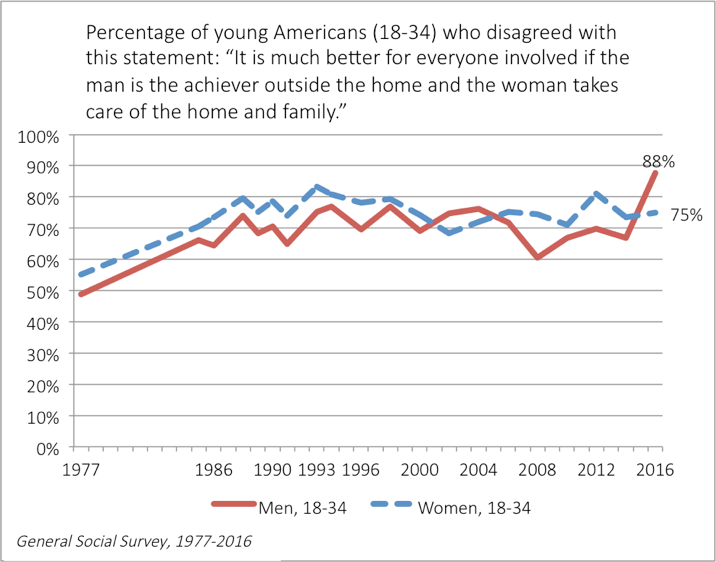

Another example is a recent op-ed from Stephanie Coontz in The New York Times: “How to Make Your Marriage Gayer.” This piece is packed with current social science on relationships, from how couples split the housework to how they handle stress. One big takeaway from the research is better reported relationship outcomes for same-sex couples, and Coontz explains this in terms of our unquestioned assumptions about our love lives. Heterosexual couples tend to revert to more traditional assumptions about gender and relationship roles. But with fewer assumptions about gender and family roles at play, same-sex couples often have to (gasp!) openly talk about their needs, negotiate expectations, and generally do the things that make a relationship really strong.

So, if you’re grumpy this Valentine’s Day, remember that there’s some good news as well. As we learn more about what makes relationships work, we make it easier to navigate romance in a more open and honest way.

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, on Twitter, or on BlueSky.