Dimitriy T.M. and Keith Marszalek sent in a video by Isao Hashimoto, posted at Wired. The video, titled 1945-1998, shows the location of all known nuclear tests during that period, as well as the nation conducting the tests. It starts off slowly (with the U.S. test during World War II and the two bombs dropped on Japan), and the U.S. has a monopoly on nuclear weapons for several years. By the early 1950s the number of tests starts to increase and the U.K. and Soviet Union start testing. By the late 1’50s and through the ’80s, the flashes indicating tests (with different sound effects to indicate different nation) are pretty much constant, and then drop off quite a lot by the ’90s.

The Wired article points out that there have been two more nuclear tests since 1998 (when the video ends), both by North Korea.

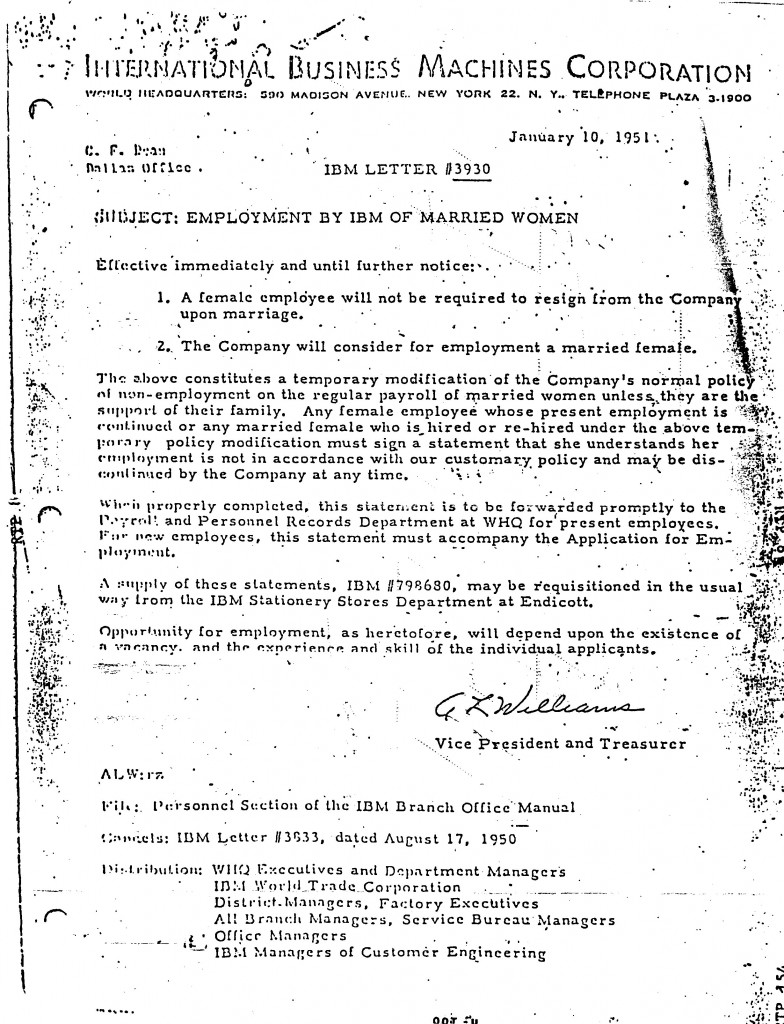

I found this graph over at the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty Organization website:

Broken down by type of test; since 1963 almost all testing has been underground:

They also have an interactive map that includes information such as who has signed the test-ban treaty, where tests have occurred, and locations of facilities under the international monitoring system. Here’s a map showing the status of the test-ban treaty; green nations have ratified it, light blue ones have signed but not ratified it, and red ones haven’t signed it (sorry I couldn’t quite fit the whole map on my screen at once, so the screenshot cuts off some areas):

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.