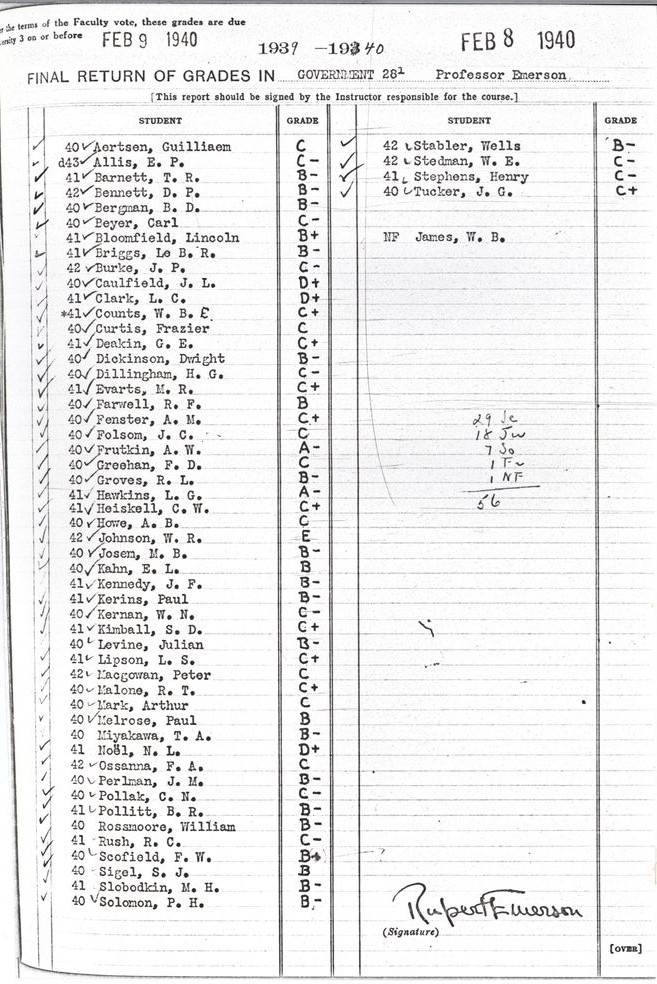

He got a B-minus. Which wasn’t so bad! He was only out-performed by 15% of his class: 5 B-pluses, 2 A-minuses, and exactly zero As. In contrast, a whopping 33% got a C or worse.

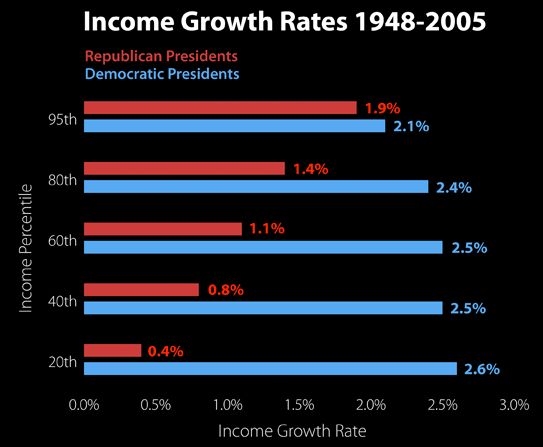

It turns out, JFK was already benefitting from grade inflation — the slow shift in the average grade point average in higher education — even in 1940. The chart below, borrowed from gradeinflation.com, shows that the average grade had gone up by 0.1 on a 4.0 scale between 1935 and Kennedy’s not-so-fateful grade report. Since then, however, has gone up another 0.7 points.

I’m well-known ’round campus for being a hard grader, but I’m no Professor Emerson.

Thanks to Matthew Beckmann for helping Kennedy’s paltry performance (I kid) see the light of day. And to Jay Livingston for bringing it to my attention. See also our post on pants inflation.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.