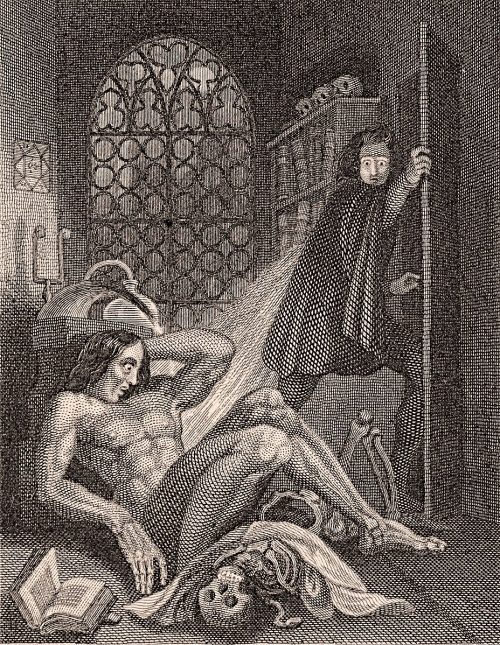

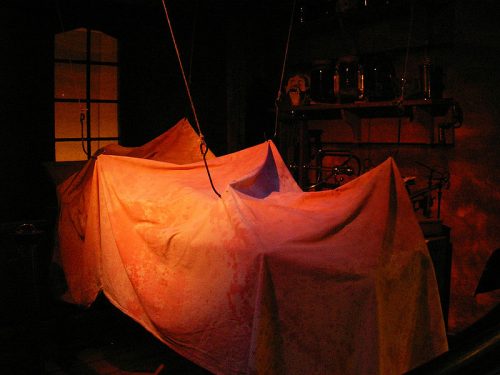

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the publication of Frankenstein. Written by a teenage Mary Shelley on a dare, this classic example of science fiction and horror explores the ethics of scientific discovery. In the story, Victor Frankenstein brings a corpse (or, many pieces of corpses sewn together) to life. Instead of continuing to study his creation, he runs away leaving it alone and defenseless. At first, the creature attempts to befriend the people he meets, but they are so offended by this specimen that they chase him away. Lonely, the creature vows to take revenge on his creator by killing Victor’s loved ones. Eventually, both the scientist and the experiment are left alone with their misery, floating off on icebergs.

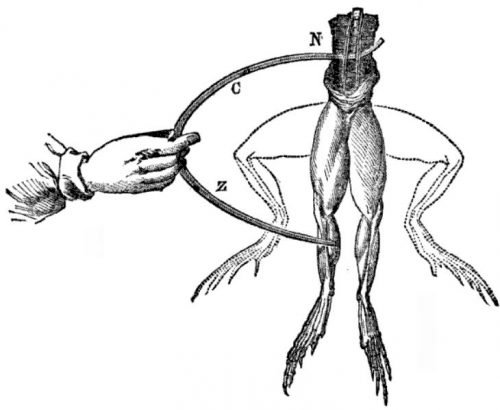

Frankenstein was based on real science at the time—Galvanism—when scholars and showmen were animating dead bodies with small electric shocks. Shelley saw some of these demonstrations and, after a few rainy night’s in Byron’s castle, penned the novel. Against this bleak backdrop, Shelley asks us to consider who is responsible for the devastation in her story? Is it the creature, a mere experiment, who caused such destruction? Is it the scientist who never took responsibility for his own work? Or, could it be the people, those who shunned the scientific anomaly because they didn’t like what they saw? What happens when other people make a monster out of your work?

We are still wrestling with these questions today as we debate gender and genetics. A recent article from Amy Harmon in The New York Times reports on communities willfully misinterpreting recent research in social science and genetics to support white supremacist views. At the same time, the department of Health and Human Services is considering establishing a formal definition of gender grounded in “scientific evidence” that could curtail civil rights protections for transgender and nonbinary people—despite the fact that biological research doesn’t support this binary view.

The scariest part of these stories isn’t just that science is taken in bad faith, it is also the confusion about who is responsible for correcting these problems. From Harmon’s article:

Many geneticists at the top of their field say they do not have the ability to communicate to a general audience on such a complicated and fraught topic. Some suggest journalists might take up the task. Several declined to speak on the record for this article.

Social science research shows that trust in scientific evidence isn’t just a matter of knowing the facts or getting them right. Trust in science requires cultural work to achieve and maintain, and political views, prior beliefs, and personal identities can all shape what kinds of evidence people accept and reject. While the media plays a big role in this work, experts also have to consider who gets to control the narrative about their findings.

The bicentennial of Frankenstein asks us to consider, this hallow’s eve, the responsibility we carry as researchers, as interpreters of research, and as those who lead people to research. It is our guidepost and our warning call. This is why we (a science educator and a sociologist) both think science education and public engagement from experts is so important. If practitioners back away from the public sphere, or if they don’t intervene when people misinterpret their work, there is a risk of letting other social and political forces make them into Victor Frankensteins. What do you think? Do experts just need to stick to the science and leave their results to everyone else? Or, do scientists need to start worrying more about their PR?

Sofia Lindgren Galloway is a STEM Educator at The Bakken Museum and a theatre artist in Minneapolis. With The Bakken Museum, Sofia performs educational plays and teaches classes about Mary Shelley, Science Fiction, and the history of electricity, among other topics.

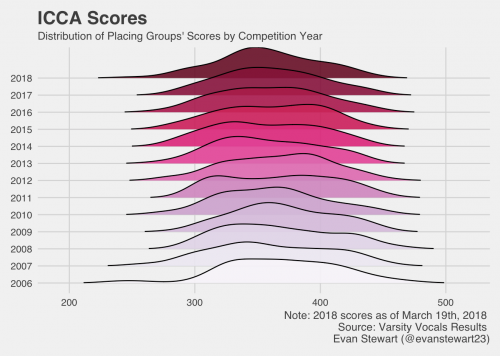

Evan Stewart is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at the University of Minnesota. You can follow him on Twitter.