U.S. Senator Susan Collins (R, Maine) and Representative Carolyn Maloney (D, New York) have both gone on record claiming that having more women employed in the Secret Service would prevent scandals like the one involving Colombian prostitutes.

U.S. Senator Susan Collins (R, Maine) and Representative Carolyn Maloney (D, New York) have both gone on record claiming that having more women employed in the Secret Service would prevent scandals like the one involving Colombian prostitutes.

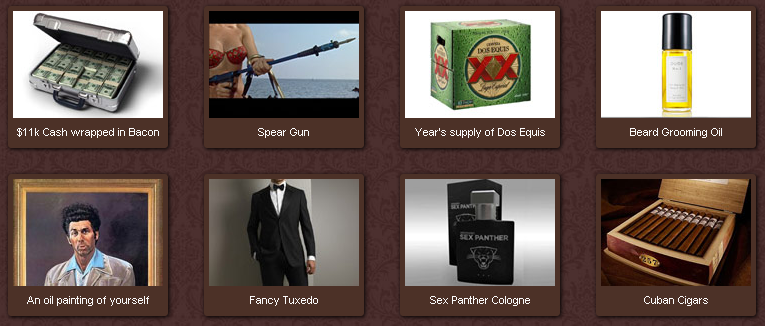

In classic Daily Show form, Jon Stewart and his “correspondents” respond (thanks to Dmitriy T.M. for the link!):

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.