Cross-posted at Speech Events.

Earlier this year President Obama described California attorney general Kamala Harris “the best-looking attorney general in the country.” Even though the crowd reportedly laughed at the comment, Obama was criticized for making sexist remarks and quickly apologized to Harris.

But some people claimed to be confused: why was Obama wrong to compliment a woman on her looks? From the Washington Times:

Please, give us a chance to learn the rules. Give us a minute to catch our breath…

We were taught (most of us were) that girls and women were to be given flowers for their beauty of character and good looks.

Exactly what is wrong with this?

But one morning we were told that it is okay, even required, to tell a woman that she looks marvelous. Next morning, hey, we can go to jail for this!

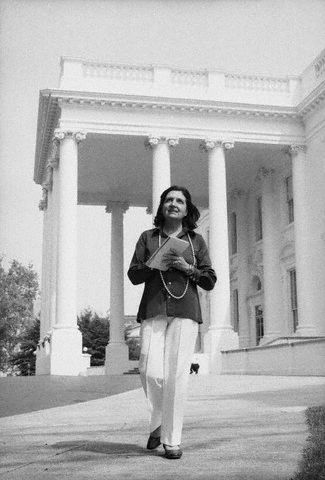

This is not the first time a president has run into this sort of trouble. This picture of reporter Helen Thomas ran in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin on August 7, 1973.*

The accompanying story was titled “Nixon Turns Fashion Critic, ‘Turn Around…’” It included the following:

President Nixon, a gentleman of the old school, teased a newspaper woman yesterday about wearing slacks to the White House and made it clear that he prefers dresses on women.

After a bill-signing ceremony in the Oval Office, the President stood up from his desk and in a teasing voice said to UPI’s Helen Thomas: “Helen, are you still wearing slacks? Do you prefer them actually? Every time I see girls in slacks it reminds me of China.”

Nixon went on, asking Thomas to present her rear:

“This is not said in an uncomplimentary way, but slacks can do something for some people and some it can’t.” He hastened to add, “but I think you do very well. Turn around.”

As Nixon, Attorney General Elliott L. Richardson, FBI Director Clarence Kelley and other high-ranking law enforcement officials smiling [sic], Miss Thomas did a pirouette for the President. She was wearing white pants, a navy blue jersey shirt, long white beads and navy blue patent leather shoes with red trim.

There are several parallels between this incident and the Obama one: they took place at the tail end of an official event, when the president apparently thought he could take some time for harmless jokes. The women involved were highly acclaimed professional women. In both events, we see a powerful man verbally change a woman from a respected professional to an attractive female.

We know how the public responded to Obama’s comment. What about reception in 1973?

First of all, Helen Thomas herself wrote the article about this incident; according to anthropologist Michael Silverstein, “this is what we call ‘payback’ time.” At first glance, it seems like a neutral report of a conversation, but take a closer look. From the very beginning, Nixon is set up as the bad guy – a “gentleman of the old school” who “teased a newspaper woman.”

The mocking, faux fashion report tone continues from the headline into the description of Thomas’s outfit. What seems like a harmless personal interest story tacked onto a news article was actually a protest against this treatment – and it required damage control by the president. Within the next week, Thomas’s fellow reporters went on the record as saying that they were on her side, and wished she had not played along with the president. Even the First Lady weighed in, saying that there was no rule against women wearing pants in the White House.

The rules haven’t changed: there’s nothing new about presidents talking about professional women’s appearance, and even in 1973 it was recognized as inappropriate.

* The image is from here; the article on google is text only.

Miranda Weinberg is a graduate student in Educational Linguistics and Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania studying multilingualism in schooling.