Ever since Hillary Clinton became the Democratic nominee for president, commentators have been speculating as to how much being a woman will hurt her chances for election. The data suggest it won’t. In fact, if anything, what we know about American voting patterns suggests that being a woman is a slight advantage over being a man.

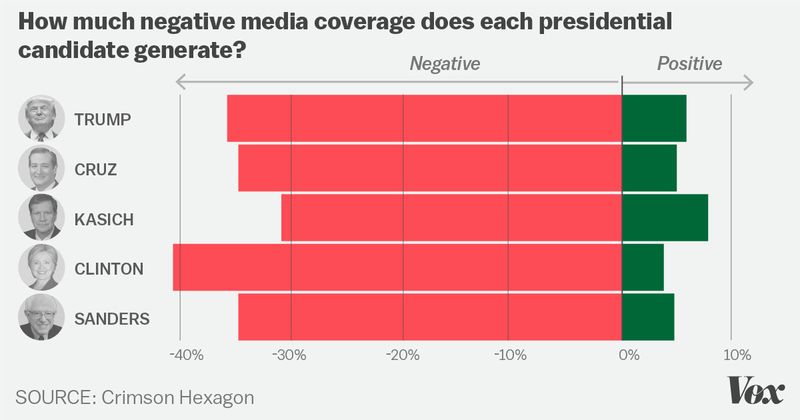

It’s not that there’s no sexism at all. Parents are more likely to encourage their sons to aspire to political office than their daughters. Women are more likely to be overburdened by childcare and housework when they’re married to men. Women are less likely than men to be tapped by powerful political party gatekeepers. And the media continues to produce biased news coverage.

But when women actually get on the ballot they are as likely to win an election as men. In fact, men in the United States seem rather indifferent towards a candidate’s sex, whereas women tend to prefer females.

Gender stereotypes still apply: voters tend to think that men are better at handling masculine areas of governance like foreign affairs and the economy, but they tend to think that women are better at feminized areas like health care and education. This means that being female can help or hurt a candidate, depending on which issues dominate the election. But, when looked at as an aggregate, gender stereotypes don’t hurt women more than men.

So, there’s one thing we can be reasonably sure of this November: If Clinton loses and Trump wins, it is unlikely to be because the American electorate is too sexist to elect a woman.

.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

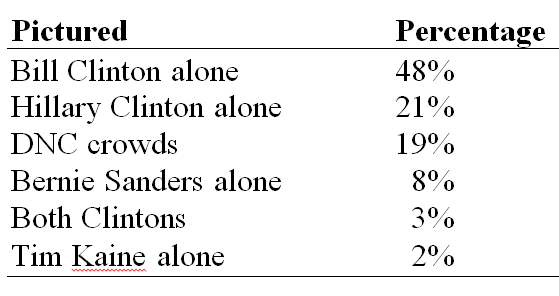

On Tuesday the first female presidential candidate was officially nominated by a major party. Newspaper headlines across the country referenced the historic event with headlines like “Historic First!” and “Clinton Makes History!” but a surprising number featured photographs of Bill instead of Hillary Clinton. I coded the pictures of each of the 266 newspapers that ran the story on the front page on July 27th (cataloged at

On Tuesday the first female presidential candidate was officially nominated by a major party. Newspaper headlines across the country referenced the historic event with headlines like “Historic First!” and “Clinton Makes History!” but a surprising number featured photographs of Bill instead of Hillary Clinton. I coded the pictures of each of the 266 newspapers that ran the story on the front page on July 27th (cataloged at