Originally posted at Gender & Society

Last summer, Donald Trump shared how he hoped his daughter Ivanka might respond should she be sexually harassed at work. He said, “I would like to think she would find another career or find another company if that was the case.” President Trump’s advice reflects what many American women feel forced to do when they’re harassed at work: quit their jobs. In our recent Gender & Society article, we examine how sexual harassment, and the job disruption that often accompanies it, affects women’s careers.

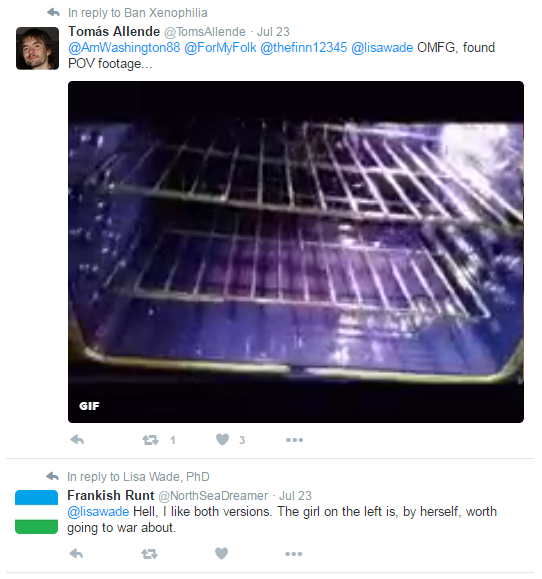

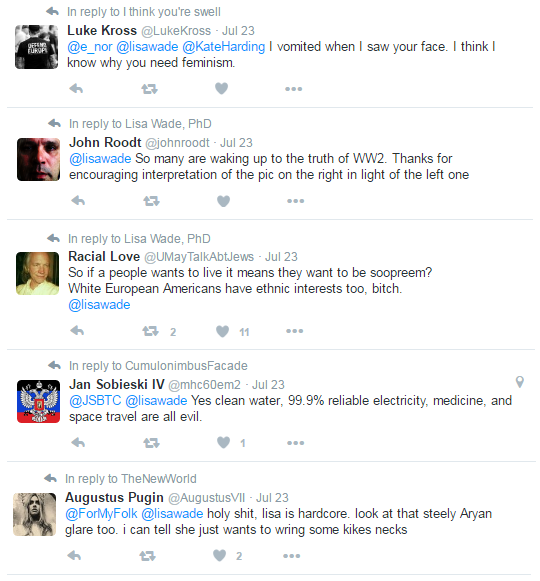

How many women quit and why? Our study shows how sexual harassment affects women at the early stages of their careers. Eighty percent of the women in our survey sample who reported either unwanted touching or a combination of other forms of harassment changed jobs within two years. Among women who were not harassed, only about half changed jobs over the same period. In our statistical models, women who were harassed were 6.5 times more likely than those who were not to change jobs. This was true after accounting for other factors – such as the birth of a child – that sometimes lead to job change. In addition to job change, industry change and reduced work hours were common after harassing experiences.

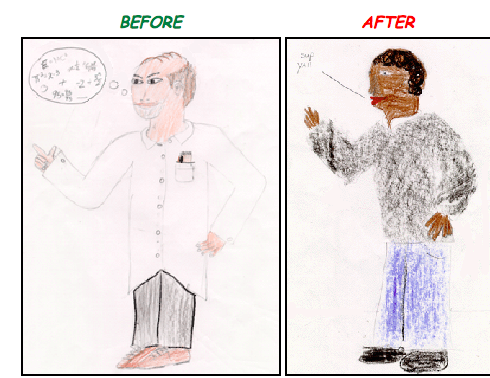

Percent of Working Women Who Change Jobs (2003–2005)

In interviews with some of these survey participants, we learned more about how sexual harassment affects employees. While some women quit work to avoid their harassers, others quit because of dissatisfaction with how employers responded to their reports of harassment.

Rachel, who worked at a fast food restaurant, told us that she was “just totally disgusted and I quit” after her employer failed to take action until they found out she had consulted an attorney. Many women who were harassed told us that leaving their positions felt like the only way to escape a toxic workplace climate. As advertising agency employee Hannah explained, “It wouldn’t be worth me trying to spend all my energy to change that culture.”

The Implications of Sexual Harassment for Women’s Careers Critics of Donald Trump’s remarks point out that many women who are harassed cannot afford to quit their jobs. Yet some feel they have no other option. Lisa, a project manager who was harassed at work, told us she decided, “That’s it, I’m outta here. I’ll eat rice and live in the dark if I have to.”

Our survey data show that women who were harassed at work report significantly greater financial stress two years later. The effect of sexual harassment was comparable to the strain caused by other negative life events, such as a serious injury or illness, incarceration, or assault. About 35 percent of this effect could be attributed to the job change that occurred after harassment.

For some of the women we interviewed, sexual harassment had other lasting effects that knocked them off-course during the formative early years of their career. Pam, for example, was less trusting after her harassment, and began a new job, for less pay, where she “wasn’t out in the public eye.” Other women were pushed toward less lucrative careers in fields where they believed sexual harassment and other sexist or discriminatory practices would be less likely to occur.

For those who stayed, challenging toxic workplace cultures also had costs. Even for women who were not harassed directly, standing up against harmful work environments resulted in ostracism, and career stagnation. By ignoring women’s concerns and pushing them out, organizational cultures that give rise to harassment remain unchallenged.

Rather than expecting women who are harassed to leave work, employers should consider the costs of maintaining workplace cultures that allow harassment to continue. Retaining good employees will reduce the high cost of turnover and allow all workers to thrive—which benefits employers and workers alike.

Heather McLaughlin is an assistant professor in Sociology at Oklahoma State University. Her research examines how gender norms are constructed and policed within various institutional contexts, including work, sport, and law, with a particular emphasis on adolescence and young adulthood. Christopher Uggen is Regents Professor and Martindale chair in Sociology and Law at the University of Minnesota. He studies crime, law, and social inequality, firm in the belief that good science can light the way to a more just and peaceful world. Amy Blackstone is a professor in Sociology and the Margaret Chase Smith Policy Center at the University of Maine. She studies childlessness and the childfree choice, workplace harassment, and civic engagement.

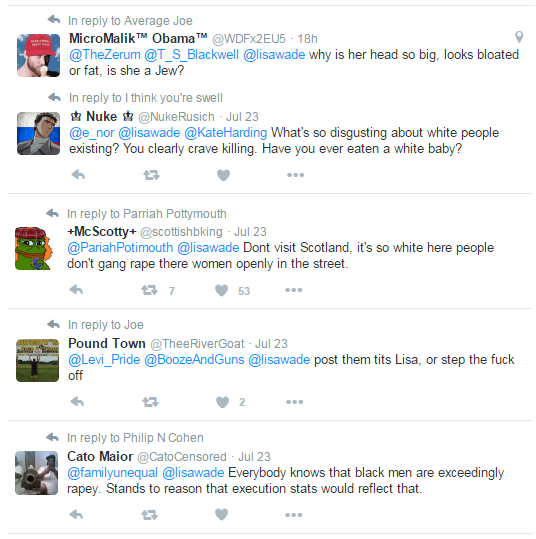

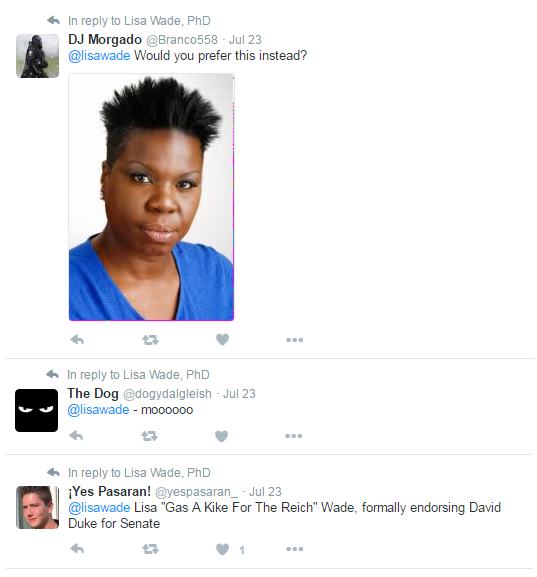

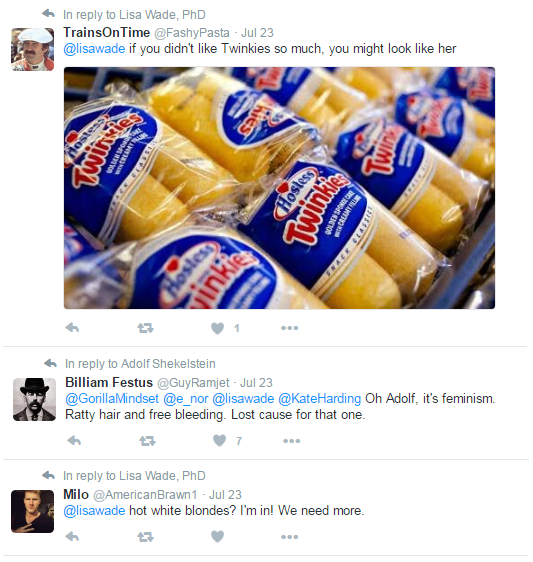

Botox has forever transformed the primordial battleground against aging. Since the FDA approved it for cosmetic use in 2002, eleven million Americans have used it. Over 90 percent of them are women.

Botox has forever transformed the primordial battleground against aging. Since the FDA approved it for cosmetic use in 2002, eleven million Americans have used it. Over 90 percent of them are women.