Ada A., Katrin, Filip S., and Missives from Marx all let us know about PinkStinks, a campaign in the UK that “challenges the culture of pink which invades every aspect of girls’ lives”.

The aim is a worthy one: the webpage discusses concerns about girls’ body image, self esteem issues, the sexualization of young women, and so on.

They link to this video, which I thought was neat:

While I totally get the idea and support the effort to provide girls with a wider set of images of what they can aspire to do or be like, the “pink stinks” name, and some of the t-shirts on the site, give me a some pause.

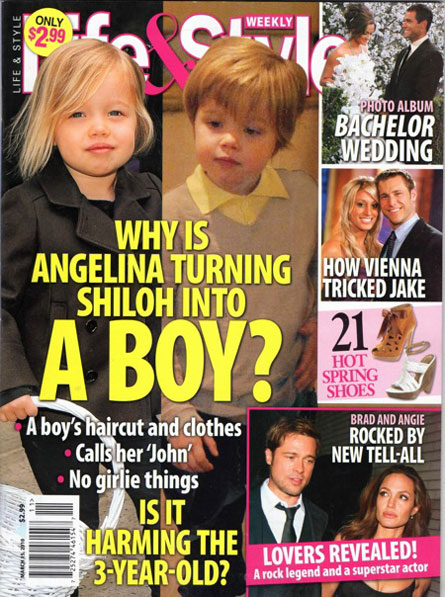

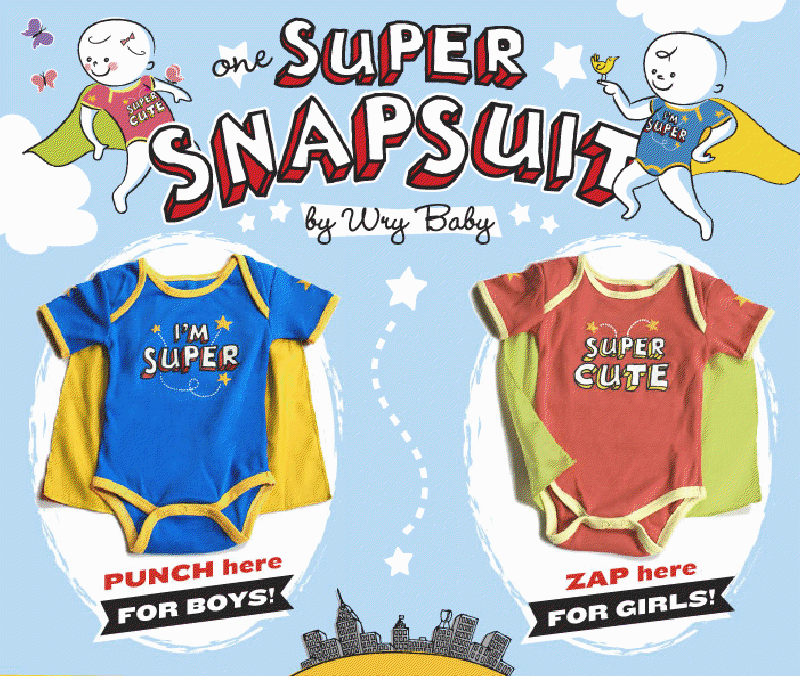

If you read different parts of the site, it’s clear that pink is a stand-in for the socialization of girls into a particular type of femininity, and the campaign is attempting to combat the narrowing of girls’ aspirations and role models. But it brings up an issue I face whenever I’m trying to pick out clothes for my 3-year-old niece: how do you reject the trappings of that socially-approved version of femininity without devaluing femininity, girls, and women themselves? All things equal, I’ll usually pick a green t-shirt instead of a pink t-shirt for my niece because I feel like giving her a pink t-shirt signals to her an approval of all the things we associate with “pink culture”–valuing looks over smarts, worrying about boys, and so on, and because I know she is frequently encouraged to declare pink her “favorite” color by those buying her gifts.

But we often see that in the attempt to provide girls with more options, those who accept elements of mainstream femininity are devalued. My students who are trying to distance themselves from ideas of passive femininity often disparage “girly-girls,” those they see as unambiguously accepting pink culture. Thus, wearing a sparkly barrette or painting your nails pink becomes inherently problematic, a sign that you must be boy-obsessed, dumb, superficial, and so on.

I don’t think this campaign overall is doing that–if you read through it, the message is more complex and clearly about giving girls a wider array of options to choose from as they construct their identities. But much of the online discussion of it seems to miss the nuance and veer more into the simplistic interpretation of “pink stinks” as “empowering girls means rejecting and devaluing everything currently associated with femininity, as well as those who do it,” and the t-shirts seem to play into that a little.

Many of the things associated with femininity–being nurturing, say, or liking to cook–are, in fact, quite lovely, and problematic only when we say that only girls can/should like them, that all girls ought to, and that they’re less worthwhile than things boys do. Adding to the devaluing of women and femininity in an attempt to resist gender norms is, ultimately, counter-productive.

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.